New drugs might look to disable this switch to drive effective immune recognition and, hopefully, produce better treatment outcomes for affected patients

Hugo Snippert

Dr Suzanne van der Horst from University Medical Center Utrecht said: “Our study reveals that DNA repair mutations in the MSH3 and MSH6 genes act as a genetic switch that cancers exploit to navigate an evolutionary balancing act. On one hand, these tumours roll the dice by turning off DNA repair to escape the body’s defence mechanisms. While this unrestrained mutation rate kills many cancer cells, it also produces a few ‘winners’ that fuel tumour development. The really interesting finding from our research is what happens afterwards. It seems the cancer turns the DNA repair switch back on to protect the parts of the genome that they too need to survive and to avoid attracting the attention of the immune system. This is the first time that we’ve seen a mutation that can be created and repaired over and over again, adding it or deleting it from the cancer’s genetic code as required.”

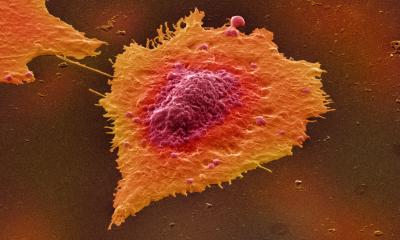

The DNA repair mutations in question occur in repetitive stretches of DNA found throughout the human genome, where one individual DNA letter (an A, T, C or G) is repeated many times. Cells often make small copying mistakes in these repetitive stretches during cell division, such as changing eight Cs into seven Cs, which disrupts gene function.

Dr Hamzeh Kayhanian, first author of the study from UCL Cancer Institute and UCLH, said: “The degree of genetic disarray in a cancer was previously thought to be purely down to chance accumulation of mutations over many years. Our work shows that cancer cells covertly repurpose these repetitive tracts in our DNA as evolutionary switches to fine-tune how rapidly mutations accumulate in tumour cells. Interestingly, this evolutionary mechanism had previously been found as a key driver of bacterial treatment resistance in patients treated with antibiotics. Like cancer cells, bacteria have evolved genetic switches which increase mutational fuel when rapid evolution is key, for example when confronted with antibiotics. Our work thus further emphasises similarities between evolution of ancient bacteria and human tumour cells, a major area of active cancer research.”

The researchers say that this knowledge could potentially be used to gauge the characteristics of a patient’s tumour, which may require more intense treatment if DNA repair has been switched off and there is potential for the tumour to adapt more quickly to evade treatment – particularly to immunotherapies, which are designed to target heavily mutated tumours. A follow-up study is already underway to find out what happens to these DNA repair switches in patients who receive cancer treatment.

Dr Hugo Snippert, a senior author of the study from University Medical Center Utrecht, said: “Overall our research shows that mutation rate is adaptable in tumours and facilitates their quest to obtain optimal evolutionary fitness. New drugs might look to disable this switch to drive effective immune recognition and, hopefully, produce better treatment outcomes for affected patients.”

This research was funded with grants from Cancer Research UK, the Rosetrees Trust, and Bowel Research UK.

Georgia Sturt, Research and Grants Manager at Bowel Research UK, said: “Cancer’s evasion of immune system destruction is a key element of its ability to grow and spread. Understanding exactly how bowel cancers do this is crucial to optimising treatment for patients. Bowel Research UK are delighted that our funding has contributed to producing this exciting new data, and we look forward to seeing how these discoveries could change treatments for future patients.”

Source: University College London