Too many older Australians are missing out on recommended vaccinations for COVID, flu, shingles and pneumococcal that can protect them from serious illness, hospitalisation and even death.

A new Grattan Institute report shows vaccination rates vary widely from GP to GP, highlighting an important place to look for opportunities to boost vaccination.

Many people get vaccinated at pharmacies, and those vaccinations are counted in our analysis. But we looked at GPs because they have a unique role overseeing someone’s health care, and an important role promoting vaccination.

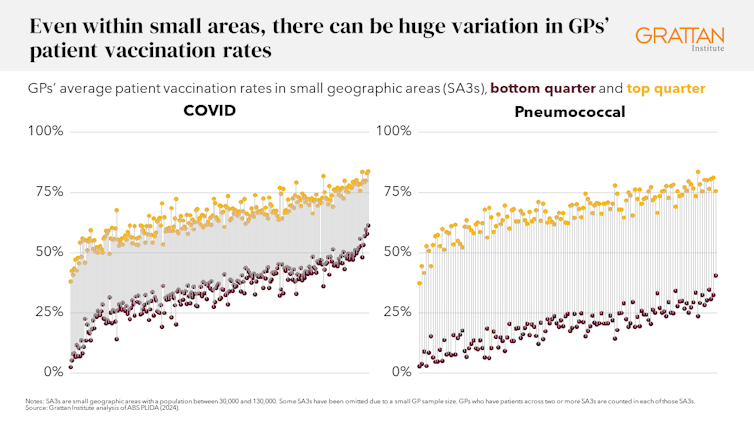

We found that for some GPs, nine in ten of their older patients were vaccinated for flu. For others, the rate was only four in ten. The differences for shingles and COVID were even bigger. For pneumococcal disease, there was a 13-fold difference in GPs’ patient vaccination rates.

While some variation is inevitable, these differences are large, and they result in too many people missing out on recommended vaccines.

Grattan Institute

Some GPs treat more complex patients

A lot of these differences reflect the fact that GPs see different types of patients.

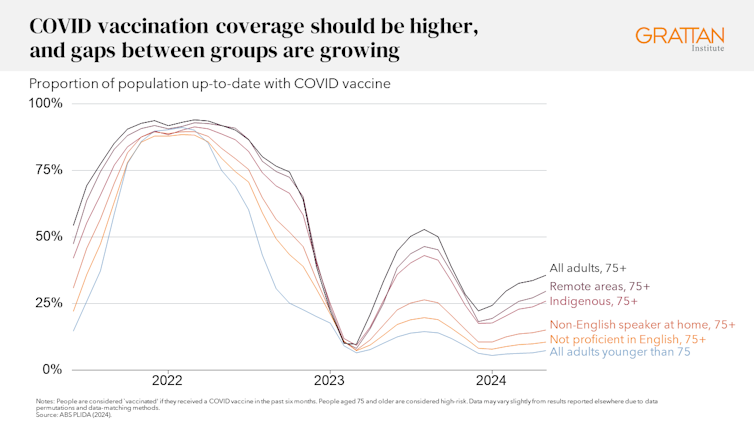

Our research shows older people who aren’t proficient in English are up to 15% less likely to be vaccinated, even after other factors are taken into account. And the problem seems to be getting worse.

COVID vaccination rates for people 75 years and older fell to just 36% in May 2024. But rates were even lower – a mere 11% – for people who don’t speak English proficiently, and 15% for those who speak a language other than English at home.

Grattan Institute

Given these results, it’s no surprise that GPs with fewer patients who are vaccinated also have more patients who struggle with English. For GPs with the lowest vaccination rates, one-quarter of their patients aren’t proficient in English. For GPs with the highest vaccination rates, it is only 1%.

GPs with fewer vaccinated patients also saw more people who live in rural areas, are poorer, didn’t go to university, and don’t have regular access to a GP, all of which reduce the likelihood of getting vaccinated.

Many of these barriers to vaccination are difficult for GPs to overcome. They point to structural problems in our health system, and indeed our society, that go well beyond vaccination.

But GPs are also a key part of the puzzle. A strong recommendation from a GP can make a big difference to whether a patient gets vaccinated. Nearly all older Australians visit a GP every year. And some GPs have room for improvement.

But GPs seeing similar patients can have very different vaccination rates

We compared GPs whose patients had a similar likelihood of being vaccinated, based on a range of factors including their health, wealth and cultural background.

Among the GPs whose patients were least likely to get a flu vaccination, some saw less than 40% of their patients vaccinated, while for others in that group, the rate was over 70%.

Among GPs with patients who face few barriers to vaccination, the share of their patients who were vaccinated also varied widely.

Even within neighbourhoods, GP patient vaccination rates vary a lot. For example, in Bankstown in Sydney, there was a seven-fold difference in COVID vaccination rates and an 18-fold difference for pneumococcal vaccination.

Grattan Institute

Not everything about clinics and patients can be measured in data, and there will be good reasons for some of these differences.

But the results do suggest that some GPs are beating the odds to overcome patient barriers to getting vaccinated, while other GPs could be doing more. That should trigger focused efforts to raise vaccination rates where they are low.

So what should governments do?

A comprehensive national reform agenda is needed to increase adult vaccination. That includes clearer guidance, national advertising campaigns, SMS reminders, and tailored local programs that reach out to communities with very low levels of vaccination.

But based on the big differences in GPs’ patient vaccination rates, Australia also needs a three-pronged plan to help GPs lift older Australians’ vaccination rates.

First, the way general practice is funded needs to be overhauled, providing more money for the GPs whose patients face higher barriers to vaccination. Today, clinics with patients who are poorer, sicker and who struggle with English tend to get less funding. They should get more, so they can spend more time with patients to explain and promote vaccination.

Second, GPs need to be given data, so that they can easily see how their vaccination rates compare to GPs with similar patients.

And third, Primary Health Networks – which are responsible for improving primary care in their area – should give clinics with low vaccination rates the help they need. That might include running vaccination sessions, sharing information about best practices that work in similar clinics with higher vaccination rates, or offering translation support.

And because pharmacies also play an important role in promoting and providing vaccines, governments should give them data too, showing how their rates compare to other pharmacies in their area, and support to boost vaccination uptake.

These measures would go a long way to better protect some of the most vulnerable in our society. Governments have better data than ever before on who is missing out on vaccinations – and other types of health care.

They shouldn’t miss the opportunity to target support so that no matter where you live, what your background is, or which GP or pharmacy you go to, you will have the best chance of being protected against disease.