A perfect storm of financial headwinds has severely impacted Australian households.

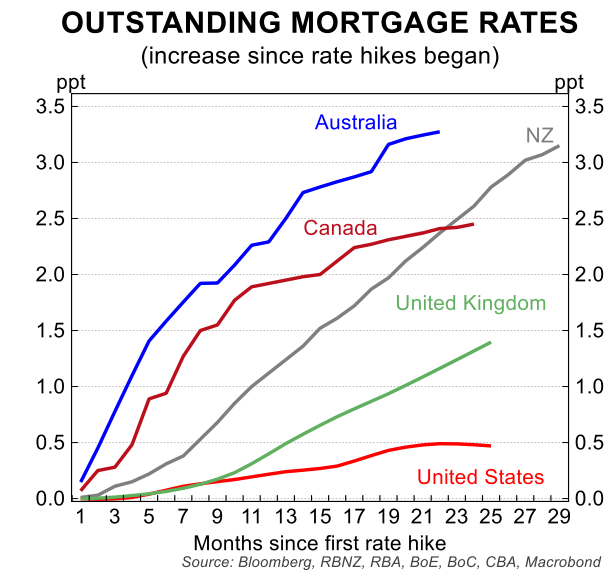

The Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) aggressive interest rate hikes have driven mortgage rates up by more in Australia than almost any other nation:

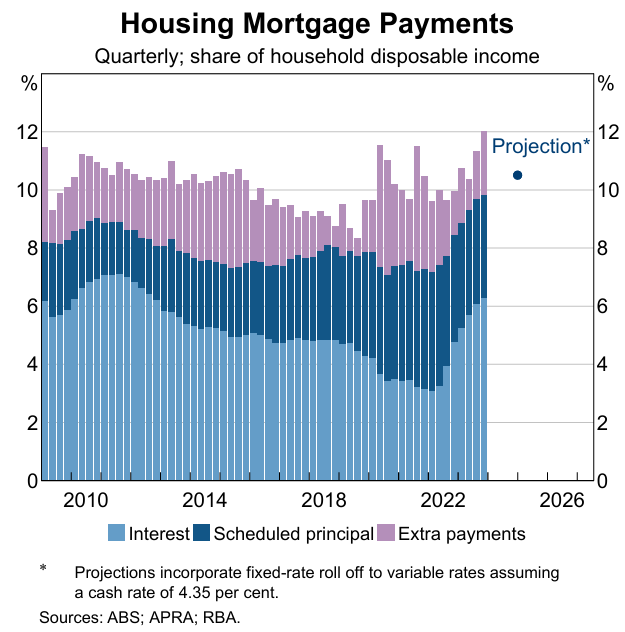

As a result, mortgage holders are dedicating a record high share of their incomes to mortgage repayments:

Advertisement

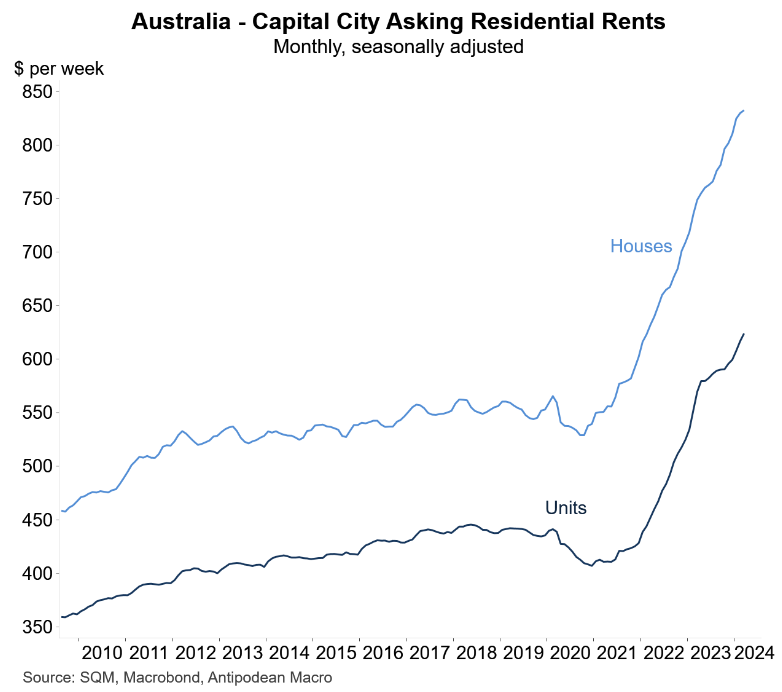

Australian tenants are also being hammered by soaring rents, courtesy of the Albanese government’s record immigration program:

Advertisement

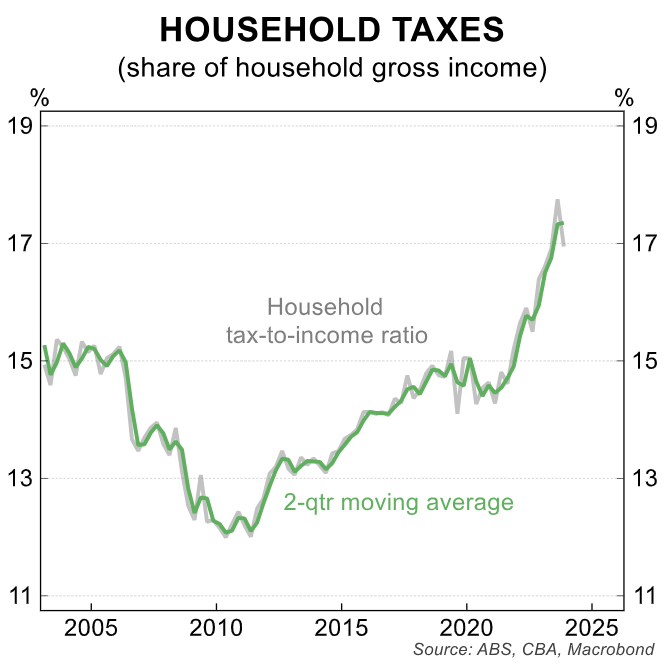

Australian households have also been hit hard by rising income tax payments courtesy of bracket creep and the expiry of the lower-middle income tax offset:

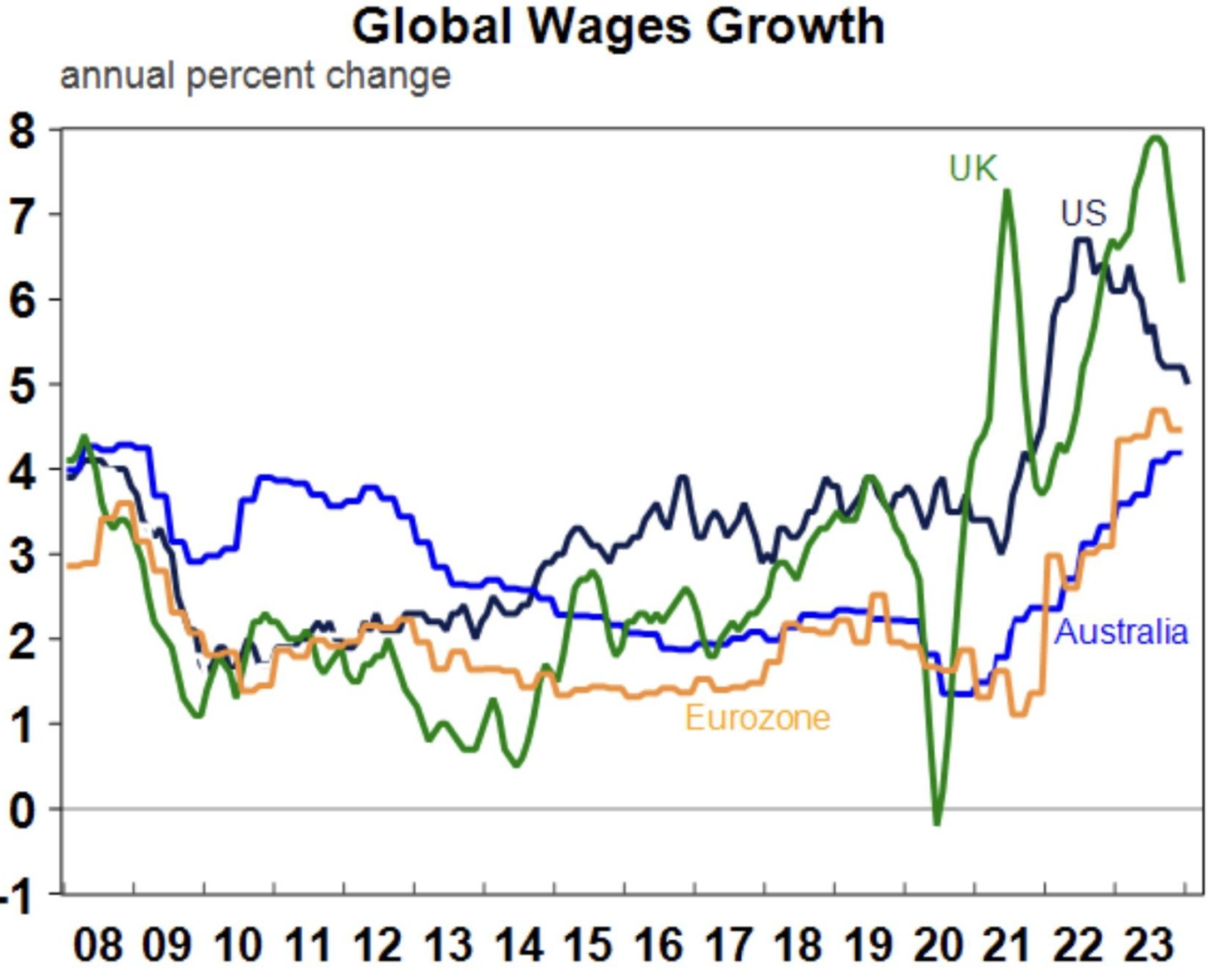

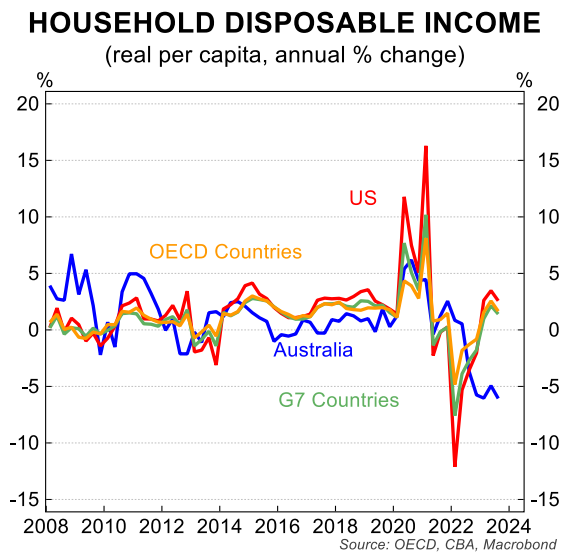

The culmination of the above pressures, alongside Australia’s relatively weak wage growth, has caused a sharp fall in real per capita household disposable income.

Advertisement

Source: AMP

Australia’s real per capita household disposable income fell by 6% last year, one of the biggest declines in the world:

Advertisement

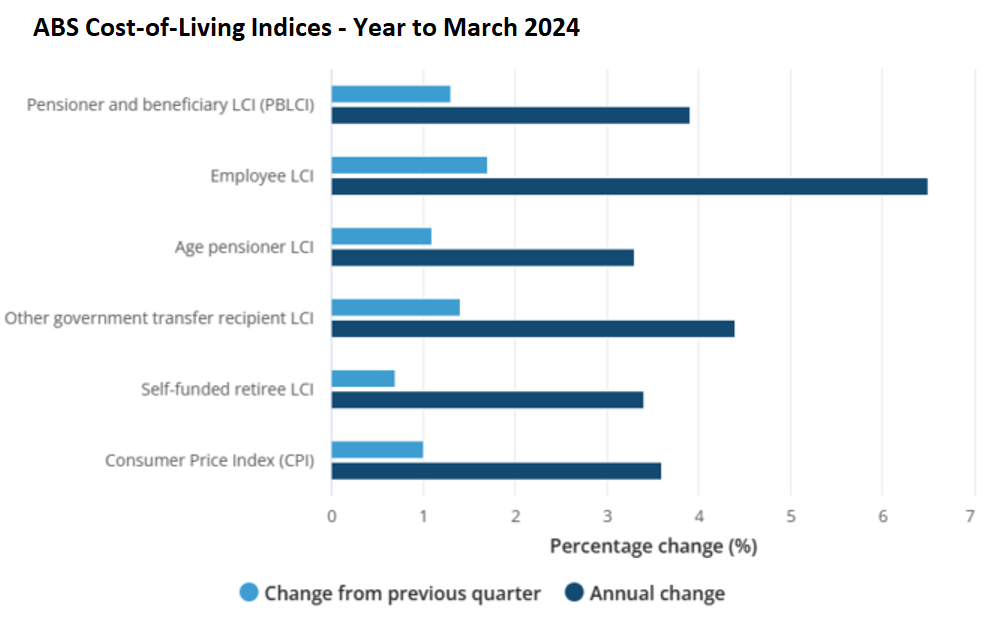

Meanwhile, Australian employee households have experienced the sharpest increase in their cost-of-living, which rose by 6.5% in the year to March 2024:

This 6.5% rise in employee household cost-of-living easily exceeded the 3.6% increase in CPI inflation or the 4.1% rise in the wage price index over the same period.

Advertisement

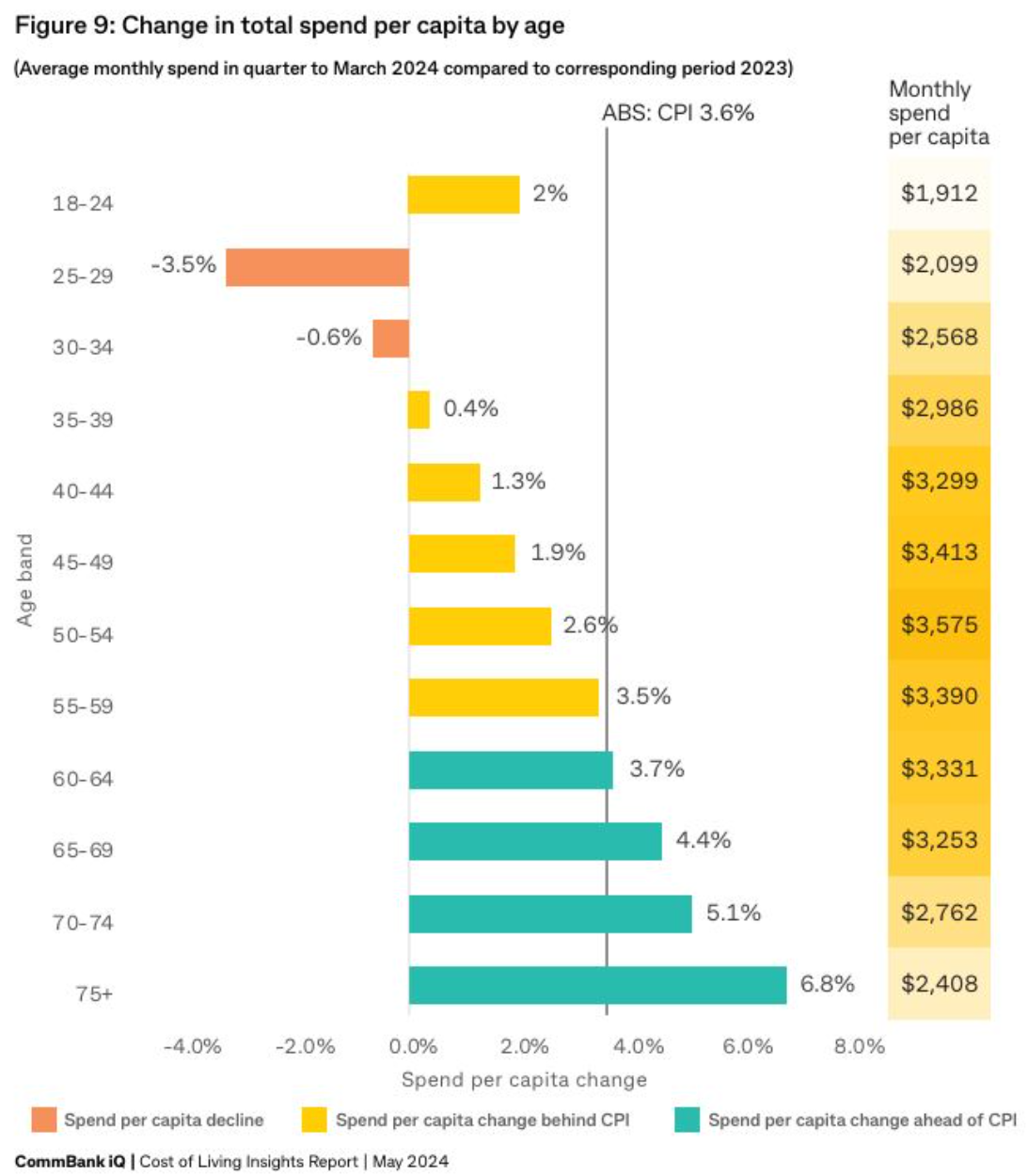

While working Australians are being buffeted by rising taxes, interest rates, and cost-of-living, older Australians are travelling well.

As illustrated in the chart directly above, the cost of living for self-funded retirees and aged pensioners rose by only 3.4% and 3.3% respectively in the year to March 2024, below the 3.6% increase in CPI inflation.

These cohorts typically own their homes outright, therefore, they have remained relatively untouched by surging mortgage repayments, rents, and personal income taxes.

Advertisement

Older Australians have also increased their spending by more than inflation, while younger Australians have been forced to cut their spending in real terms:

This spending by older Australians is helping to keep CPI inflation elevated, which is preventing the RBA from lowering interest rates and, thereby, is hurting younger Australians carrying mortgages.

Advertisement

The above data highlights why Australia should raise the rate of GST to 15%.

Doing so would pull wealthy older Australians into the taxation net, reduce the reliance on personal income taxes, and slow spending and aggregate demand (other things equal).

Equity concerns—for example, the impacts on lower income earners or Australians on fixed incomes—could be mitigated with direct fiscal transfers or rebates to these groups.

Advertisement

Raising the GST in this way would certainly be much fairer than continually punishing one-third of Australians carrying owner-occupier mortgages with higher interest rates and punishing working Australians with forever higher income taxes.

The tax system, as it is currently set, is an all out war on youth and working Australians.