CNN

—

On the cover of Lisa Birnbach’s “The Official Preppy Handbook,” a tongue-in-cheek 1980s guide to looking, acting and thinking like a US prep school elite, a pattern along the border depicts a fabric that has become synonymous with casual American luxury: madras.

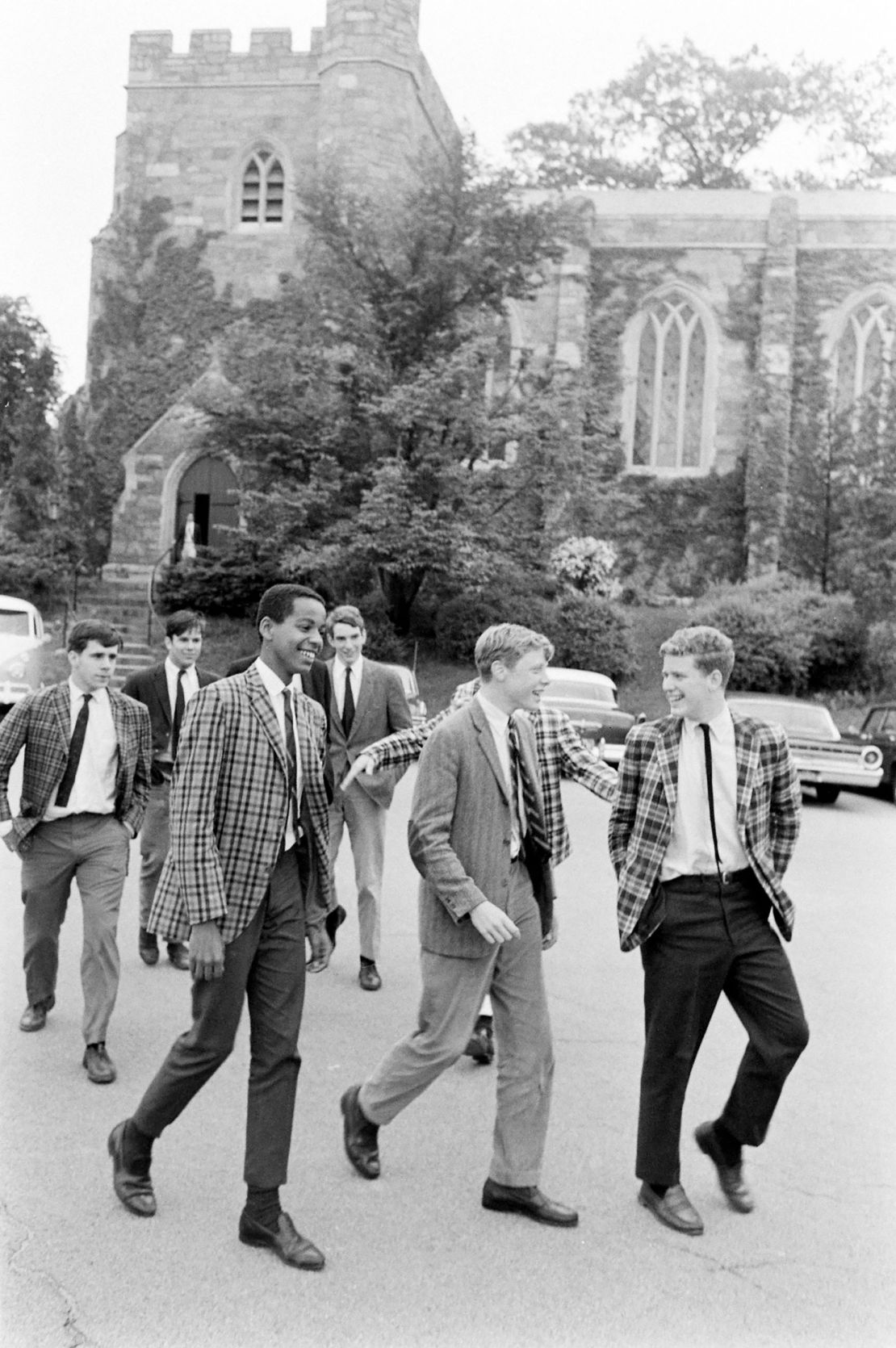

The colorful plaid cotton cloth has been used by brands like Ralph Lauren and Brooks Brothers for decades. Think light summer dresses, shirts and shorts worn at the country club or on sailing holidays in the Bahamas — the kind of attire that might be complemented by a pair of leather boat shoes.

But this staple of preppy American fashion has humble origins, far from Martha’s Vineyard or the hallways of Yale or Harvard, in Chennai, India, the coastal city from which it takes its name. (Chennai was known as Madras during British rule.) Originally worn by Indian laborers, the cloth almost sparked a corporate scandal for American textile importer William Jacobson in 1958 due to its tendency to bleed when cleaned with strong detergent in high-powered washing machines.

“The fascinating thing was that with every wash, the colors bled into each other. And they didn’t do it badly. They bled in a very ‘design’ kind of way,” said Bachi Karkaria, author of “Capture the Dream: The Many Lives of Captain C.P. Krishnan Nair,” a biography of the Indian textile magnate and hotelier who first sold Jacobson the madras, in a video interview with CNN. “This is what absolutely attracted Jacobson.”

In her book, Karkaria tells the story of Jacobson and Nair’s meeting — Nair rattling off the unique selling points of the fabric, which was woven using lightweight 60-count yarn for the warp (thread held in place on the loom) and slightly heavier 40-count yarn for the weft (thread woven horizontally through the warp) before being dyed. The natural dyes were made from laterites, indigo blue, turmeric and local sesame seed oil, all of which gave the cloth a distinctive scent. Madras was, by the 1950s, already a hit in West Africa where it was used to make flamboyant gowns for weddings and other celebrations.

But the most exciting quality Nair pitched to Jacobson, Karkaria said, was the fabric’s weakness-as-strength — it would bleed with every wash, creating a new kind of check and a “new” garment. The pair struck a dollar-a-yard deal (about $10 per yard in today’s money), with an immediate shipment of 10,000 yards that was entirely scooped up by Brooks Brothers and tailored into sporty jackets, shirts and shorts.

“Laidback post–World War II baby boomers couldn’t have enough,’” she wrote, noting that shelves with madras clothing were stripped within a week.

But, in his excitement, Jacobson forgot to tell Brooks Brothers the fabric would bleed, the author said. When the label failed to provide buyers with proper care instructions, complaints and lawsuits started rolling in. “All hell broke loose because customers found that their colors would ‘bleed’ not only into the fabric’s own checks but also run into the other clothes which were unwittingly washed along with them,” wrote Karkaria.

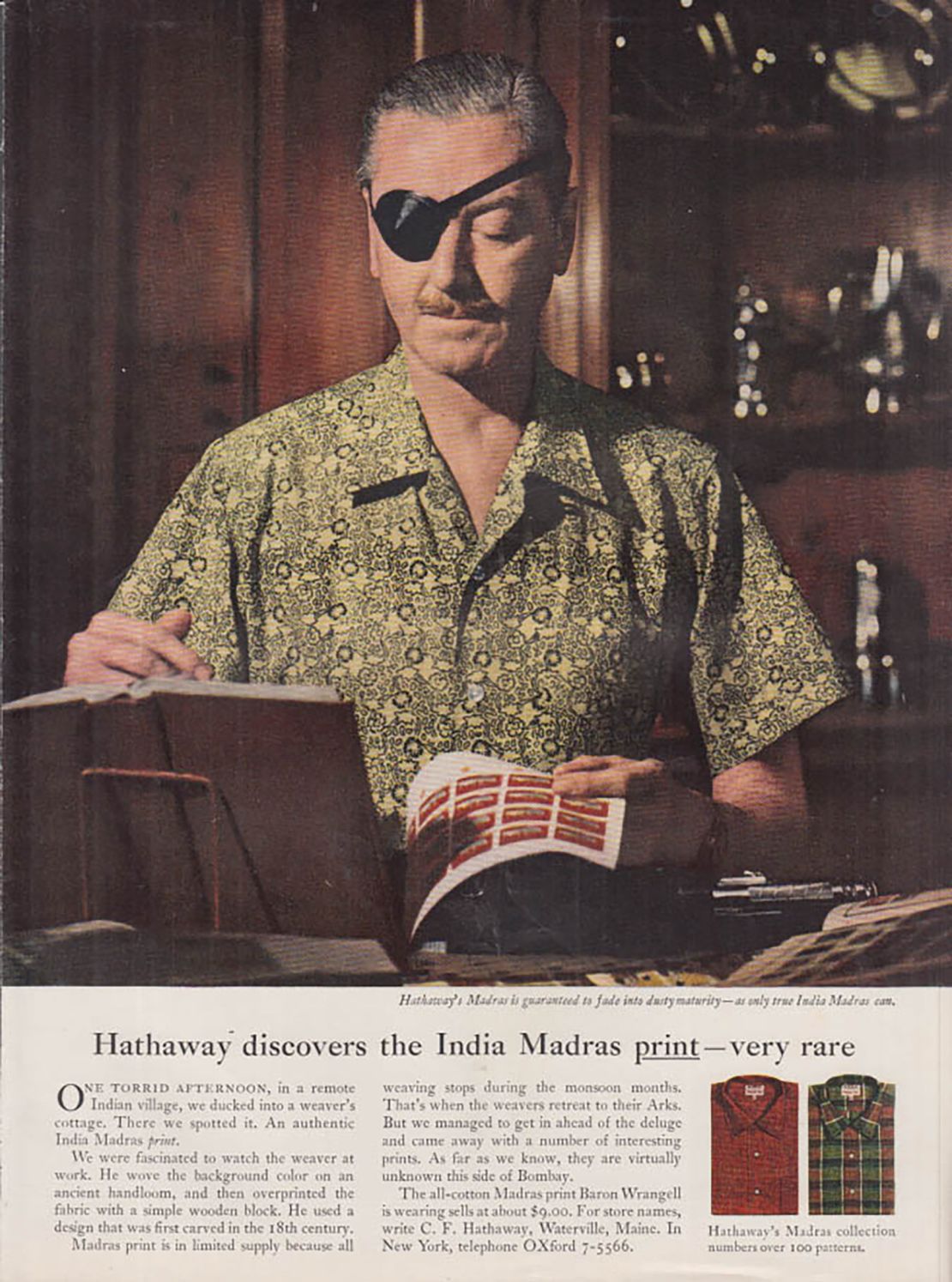

One of New York’s original “Mad Men” was called in to salvage the situation — British advertising tycoon David Ogilvy, who ended up coining the tagline “Guaranteed to Bleed,” spinning the apparent flaw into a unique selling point.

The publicity drive continued with an eight-page advertorial in Seventeen magazine on the “miracle handwoven fabric from India,” featuring an interview with Nair.

“Naturally, all the other prêt labels cottoned on, and made it part of their summer collections,” wrote Karkaria. From the brink of a PR disaster, Ogilvy had helped turn madras garments into must-haves for America’s well-heeled jet-set.

Yale links and the making of an icon

Although Ogilvy, Nair and Jacobson shot madras into superstardom in the US during the 1960s, the fabric’s link with the Ivy League had started centuries earlier with Elihu Yale, the colonial administrator of the East India Company’s Fort St. George outpost in Chennai and the primary benefactor of Yale College (now Yale University).

A 1961 advertisement, created by Ogilvy for the American men’s shirt brand Hathaway, claims that the university was founded thanks to “three trunks of India Madras” donated by Yale. Yale, who amassed much of his fortune through the East India Company in the late 17th century, sent “unusual cotton fabrics that the Indian cottagers made” to be sold or “otherwise improved” to benefit the college, the ad reads.

“The handsome stuff brought enough money to finish the buildings for the new college, which grateful trustees promptly named after Eli Yale,” continues the ad, which may have employed some creative license, given it says it chose its name after Yale donated “the proceeds from the sale of nine bales of goods together with 417 books and a portrait of King George I.”

Yale himself is a controversial figure. He built his fortune off the exploitative diamond and textile trades, and while his namesake university says there is “no direct evidence” that he “personally owned slaves,” he stands accused of trading and profiting from them.

But Yale’s fabric donation wasn’t the only reason why madras became synonymous with American prep.

The fabric already had a long history by the time Yale chanced upon it. Some say it was inspired by Scottish tartans, though it differs in several important ways (madras features neither the black lines nor the two-by-two weave of tartan, and is made of cotton, not wool).

Records seen by Metropolitan Museum of Art researcher Kai Toussaint Marcel show that Portuguese merchants traded the Indian fabric in North Africa and the Middle East as far back as the 13th century, and that the Kalabari people of Nigeria used it in dresses and headdresses and during religious and spiritual rituals. Marcel, writing for the Tommy Hillfiger-backed “Fashion and Race Database, a project founded by Parsons School of Design professor Kimberly M. Jenkins, added that West African slaves brought to America likely kept these traditions, and the fabric, alive.

Fort St. George was established in the 1630s, helping the British cement a monopoly on the highly lucrative Indian textile industry. Later, the Dutch and French would also trade cotton and madras alongside enslaved Africans, bringing the fabric aboard slave ships to the West Indies. In the 18th century, a protectionist move to support domestic textile producers saw England and France ban madras from being sold in their countries, only allowing it to be traded in the Caribbean colonies. Research by the London School of Economics estimates that Indian cotton textiles, which were often exchanged for slaves, accounted for 30% of the total export value of 18th century Anglo-African trade.

From there, madras “became a staple for both free and enslaved Black people,” especially women, who “used brightly-colored madras headdresses to subvert the sumptuary laws (that limited private expenditure on food and personal items) of the Caribbean and New Orleans… which mandated plainness as a sign of inferiority,” writes Marcel.

And it was there, on the sunny shores of the Caribbean, that the cloth became an inseparable part of the prep wardrobe thanks to tourism and Ivy League rugby tournaments in the mid-1930s. Students from East Coast schools like Yale and Princeton would travel to Bermuda to play rugby and “sunbathe, splash in the surf, play in volleyball tournaments and elect a new Miss College Week,” Sports Illustrated reported in 1956. They would also “throng” local stores to “buy devalued-pound bargains in cashmere and Shetland sweaters, madras Bermuda shorts and blazers,” the article added.

As a result, Marcel wrote, madras became “associated with Ivy League schools, vacation, the Caribbean, and eventually domestic locales such as Long Island (the Hamptons), Rhode Island (Newport), and South Florida (Palm Beach and Fisher Island).

“The fabric was fashioned into everything from shirts, (pants), shorts, and blazers, to watchbands, ties, and other accessories.”

Nowadays the fabric is a little less ubiquitous, with the “quiet luxury” trend nudging brands toward a more toned-down aesthetic. And even the cover of Birnbach’s updated guide to the preppy lifestyle, “True Prep: It’s a Whole New Old World,” has replaced its madras border with another — though no less colorful — pattern: stripes.