In 1984, during the height of the Soviet-Afghan war, American photojournalist Steve McCurry took what is considered by many to be the most famous photo in the world. The photo, entitled Afghan Girl, depicts a then-12-year-old girl, identified in 2002 as Sharbat Gula, while she and her family were living in Nasir Bagh, an Afghan refugee camp in the Pakistani city of Peshawar.

The photo’s printing on the cover of the June 1985 issue of National Geographic cemented both the career of Steve McCurry and Ms. Gula’s likeness in the public consciousness, so much so that after the September 11th Attacks, she became the subject of Search for the Afghan Girl, a television documentary that set out to finally identify the girl depicted in a photo almost everyone in the world had likely already seen. The very same photo was used again by National Geographic in conjunction with a feature story on her life.

While it’s well-established that the backstory and ethics surrounding the photo itself are rather murky, especially in more recent years, there’s no denying that it stands as a testament to the power of the still image and the skill required to capture such an image.

Being someone who obsesses over gear, I recently wondered whether the equipment Mr. McCurry had used for the photo was documented anywhere, both out of genuine curiosity and because the little voice inside my head (or the devil on my shoulder, depending on how you look at it) wondered what the going rate for the setup might be and whether I could convince myself I didn’t need it to add to my collection. Imagine my delight when, after just a bit of research, I discovered that not only did I already own a Nikon F2, a close cousin of the Nikon FM2 used for the photo, but that the Nikkor 105mm f/2.5 lens he’d married it to could be had on the used market for surprisingly little coin!

After doing a bit of reading on the various iterations of the lens and finally giving into the inevitable conclusion that I would never forgive myself for not buying one, I hit up eBay and began the hunt. Like many vintage Nikon lenses, there are actually several versions of the lens, as the design evolved over its production run. Well, when I say that, I really only mean the exterior housing, because as it turns out, the original design was so good that after 1971, the only significant updates to the lens were to the housing and mount, to improve ergonomics and ensure compatibility with newer AI-equipped Nikon cameras-the optical formula of 7 aperture blades and 5 element – 4 group construction remained untouched until the lens was discontinued in 2005. For those of you playing at home, that’s 34 years of, more or less, exactly the same lens.

Like the other vintage gear I’ve begun amassing, I approached my search with a mantra I learned from hundreds of hours of Mythbusters as a child-“If it’s worth doing, it’s worth overdoing.” While some might be perfectly content to hunt for a killer deal on a worn but functional lens at a thrift shop, unfortunately for my wallet, I have a nasty penchant for convincing myself that the intangible value of knowing I have a really nice thing is worth more than the value of the additional money I have to spend to get that really nice thing.

Fortunately, though, I decided early on that I wanted to look for a copy of the second version of the lens, the Nikkor-P.C. Auto 105mm f/2.5, rather than a more modern version that tends to command slightly higher prices owing to their AI compatibility. I personally don’t have a use for the newer AI-compatible models anyway, and I happen to prefer the chunky aluminum-bodied styling of the pre-AI lenses, but I did want to benefit from both the multicoating introduced at this revision as well as the new optical formula, the same one that lasted until 2005. I waded through page after page of decent-looking listings, hunting for one that was truly exceptional.

And lo and behold, I found one. Like most of my other vintage film gear, listed by a specialty camera shop in Tokyo. It was listed as “TOP MINT”, and after a couple of days of transit, boy howdy they weren’t lying. Judging from the serial number, this lens was manufactured sometime between 1973 and the first few months of 1975, making it as near as makes no difference 50 years old, and if you had told me that the stars had aligned and Nikon had seen fit to reissue the lens as brand new, I would have believed you-it looks like it rolled out of the factory yesterday.

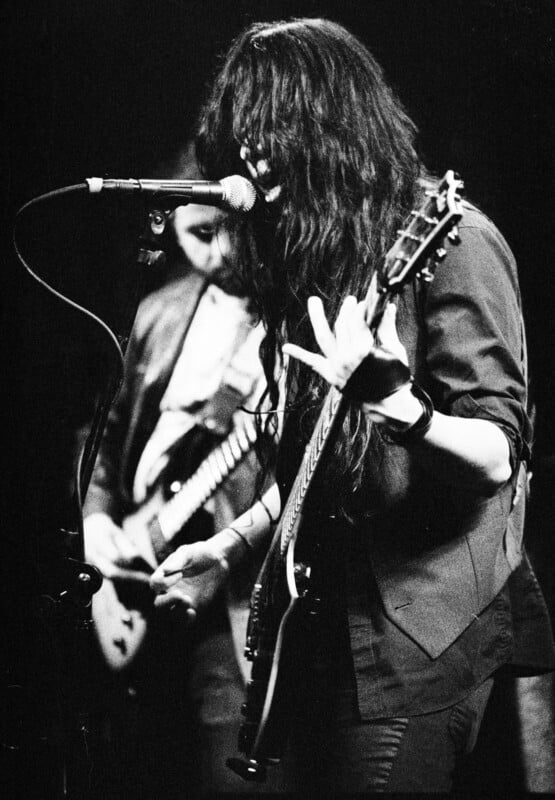

Eagerly, I mounted it up and got to shooting. Now, portraiture isn’t necessarily my bread and butter, but given that I call myself a musician of some ability (no matter how small), and I’ve been really trying to expand my portfolio of concert photography, I decided to head to a local watering hole to get some shots at that night’s Metal Mayhem, featuring several local bands.

Having shot at this venue before, it’s a bit of a bear to do well, since the performance area is rather small and lit by several rows of extremely intense but narrow-beamed colored stage lights. Such is their intensity and proximity to the performers, I often have to convert my color photos to monochrome for them to look OK, else I’m left with a collection of photos that all have their red, green, or blue channels clipped right over anything remotely reflective. Knowing this, you would think there’d be plenty of light to shoot with, but you would be wrong. Even a fast lens like an f/1.2 struggles to gather much more light than is sufficient for ISO settings of 3,200 or 6,400, at shutter speeds dangerously close to the reciprocal rule for an appropriately-long lens. Since the highest-speed film I have ready access to is Kodak P3200, my choice was already made for me.

![]()

I have to say, for a first outing, I was very impressed with both the lens and my apparent ability to get away with shutter speeds I have no business getting away with. I shot wide-open pretty much the entire night, at anywhere from 1/30s to 1/125s. For a moving subject on manual focus, hey, I’m happy.

Over the next few weeks, I tried all kinds of different film stocks-Ektar 100, Delta 100, and the surprisingly awesome Harman Phoenix 200, to name a few. I was immediately struck by the incredible color rendition and sharpness, in addition to a razor-thin depth of field at closer focusing distances that makes wide-open portraits a challenge. What’s more, it’s already exceptionally sharp wide-open, and only gets better until diffraction begins to kick in past about f/8.

![]()

105mm is a bit long for a normal walk-around lens, and it forces you to think about your surroundings in a different way than a standard focal length. Namely, what’s behind you, since you’re going to be backing up rather a lot. Your reward for doing so is incredible bokeh and subject isolation, which is exactly the kind of thing you’d hope for from a portrait lens.

![]()

I’m thrilled to have added such a fantastic lens to my collection and to my creative toolkit. I’m definitely a sucker for high-quality equipment that really speaks for itself in the kind of results it produces. As I relearn how to shoot film again, I’m excitedly looking forward to collecting more vintage gear and being its steward until it comes time to pass it on, to do my part towards preserving the old ways of doing things.