Our trans-Tasman neighbour has backtracked on its earlier commitment to ease up on controversial deportations of New Zealanders under Section 501 of the Australian Migration Act. Gabi Lardies explains.

“It’s just not right,” said prime minister Christopher Luxon on Friday, responding to news that Australia had hardened its immigration policy regarding deportees known as “501s”. He said he’d raised concerns about the issue with Australian prime minister Albanese previously, as had foreign minister Winston Peters with his Aussie counterpart Andrew Giles. “We regret the decision that Australia has made,” said Luxon. But what is a 501, and why are they getting deported?

What are 501s?

The trio of numbers has come to mean people who are deported from Australia under Section 501 of the Australian Migration Act, which allows a migrant’s visa to be cancelled if they fail a “character test”. This section was amended in 2014 under Tony Abbott’s Liberal government to lower the thresholds under which someone could fail the test (a two-year prison sentence was shortened to one, for example), and visa cancellation and refusal powers were increased (mandatory visa cancellation in cases where a person has been convicted of sexual offences involving a child, fore example).

Hardline enforcement of the policy began that same year. From that point until September 2023, 3,058 New Zealand citizens, many of whom had lived in Australia since they were children and had little or no connection with Aotearoa, were deported under this section. Most were aged between 20 and 40, and a disproportionate number were Māori. Just under half had been convicted of a criminal offence since 2015. It’s not just New Zealand – 501s are also deported to the UK, Vietnam, China, Sudan and other countries – but New Zealanders make up about half the numbers each year.

The policy affects people who have lived most of their lives in Australia but hold a New Zealand passport. Because migrants from New Zealand can live, study and work in Australia indefinitely with most of the perks of citizenship under a special category visa, many don’t seek out Australian citizenship. It is estimated that around 670,000 New Zealand citizens live in Australia. They build their lives on this visa, but it’s legally temporary, so can be revoked by the state.

Why are 501s getting deported?

The good character test covers things like imprisonment and criminal activity, as well as less clearly defined criteria like “undesirable” social associations. Most deportees do have criminal records, but they vary in their seriousness. Many people have been deported for low-level, but repeated, drug crimes and driving offences. Primarily the 501 policy applies to those who have been sentenced to 12 months or more in prison, but time sentenced to residential drug rehabilitation is being added onto actual prison time, lowering the threshold. Concurrent sentences are included, where someone might be convicted of several minor offences at the same time. A person can also be deported if the minister of home affairs reasonably suspects they do not pass the character test and is satisfied the cancellation of their visa is in “the national interest”.

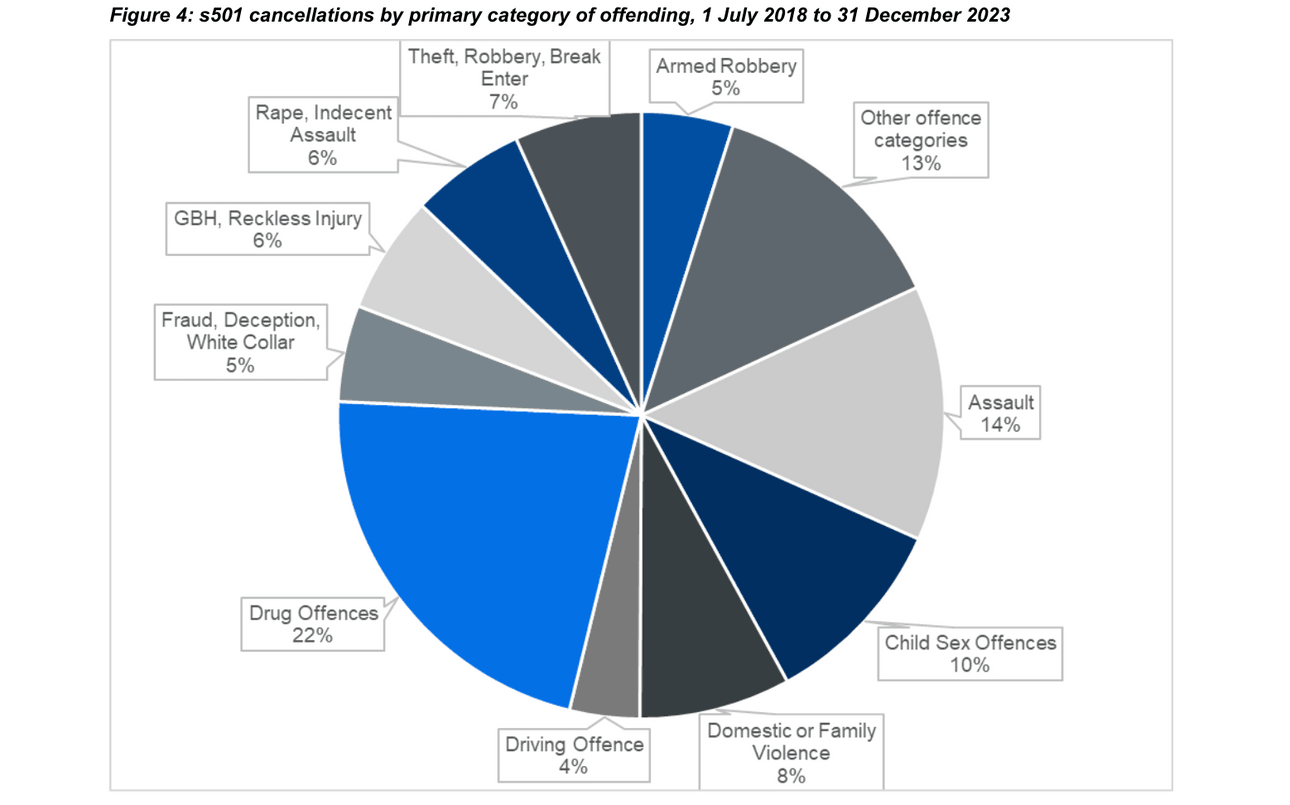

Data from Australia’s department of home affairs shows that between July 1, 2018 and December 31, 2023, the most common crime deported 501s were charged with was drug offences, at 22%. Following that is assault (14%), child sex offences (10%), and family or domestic violence (8%).

New Zealand’s argument against 501 deportations has not been about their criminality, however. It has been about the appropriateness of sending someone to a country they’ve not lived in for decades and have no connection to. Our government has long argued that the deportees, many of whom grew up in Australia and committed their crimes there, should not be our responsibility. So the issue of deportation becomes about whether Australia is dumping its problems onto other countries, namely us.

Wait, I thought Australia was going to ease up?

In July 2022, after discussions between then New Zealand prime minister Jacinda Ardern and her recently elected Australian Labor counterpart Anthony Albanese, Albanese announced a “commonsense approach” would now be applied to 501 deportations. In February the following year, ministerial direction 99 was announced, which meant the length of time someone had spent in Australia would be a “primary consideration” and given “considerable weight” regardless of their offending when determining whether a visa should be cancelled. These changes made a measurable difference – last November, the Herald reported that in the preceding 12 months, 18 people per month on average had been deported to New Zealand, less than half the the average of 44 a month in 2017/2018. While New Zealand welcomed the change and its effects, they were controversial in Australia. When it emerged that two people with criminal records and recently reinstated visas had committed murders, uproar ensued.

OK, so the softened stance didn’t last?

Under pressure, last week Albanese said that direction 99 would be abandoned, and on Friday, immigration minister Andrew Giles announced direction 110 to replace it. The new direction would make it clearer that non-citizens with a history of family or sexual violence should be deported, even if they have lived most of their lives in Australia, he said. The language about connections to Australia was stripped back, no longer explicitly stating that more weight should be given a person having children who are Australian citizens or permanent residents. Instead it says “the safety of the Australian community is the highest priority of the Australian government”.

Giles said it was “an important step in ensuring that our migration system is working always in our national interest”. But opposition leader Peter Dutton, who sparked controversy as home affairs minister in 2021 when he described New Zealanders being deported under section 501 as “taking out the trash”, said it would not lead to “much change at all”.

Luxon said he had raised his “grave concerns” about the policy change with Albanese, but added “a lot of it will depend upon how it’s implemented”.

What is deportation like for 501s?

Deportation is often life-shattering. People who have lived in Australia for most of their lives are uprooted, leaving children, partners, parents, friends and jobs behind. There’s no shortage of reported examples of 501 deportations to New Zealand where the person hasn’t been here since they were a baby. Australia is home. They arrive in a country where they know no one, and may have to depend on distant relatives or a welfare system they’re not familiar with. There is little resource for support or rehabilitation. Some have said it feels like being a refugee.

Dumped in what feels like a foreign country, 501s have difficulty building a life. Some get involved in crime and gangs. Others end up dead.

Before every deportation comes detention. In a Stuff feature from 2019, 501 Lee Barber painted a harrowing picture of his 18 months in detention. “I just can’t be in a detention centre any longer – it’s too stressful. I don’t want to look at guys [commit] suicide, I don’t want to see guys slash their wrists, I don’t want to see guys bang their heads up against brick walls, I don’t want to see violence – I’m over it.” Barber was there waiting for the decision on his appeal against the cancellations of his visa. Appeals sometimes take several years, and meanwhile people are locked in detention centres.

Gillian Trigg, president of the Australian Human Rights Commission from 2012-2017, who regularly visited Australian detention centres, said to The Spinoff in 2018, “My personal view is that these facilities are designed to break people. At one level it’s torture and at the other it’s spitefulness.” She’s said that conditions breach the United Nations Convention against torture.

Oh, and the journey is horrible too – 501s are sometimes made to walk through the airports with chained hands and feet.