The Demographia International Housing Affordability report is a widely respected annual survey of residential property across eight countries. This year’s 20th edition of the report has tonnes of great data, much of which doesn’t make for nice reading for Australia. That said, previous editions haven’t been too kind either.

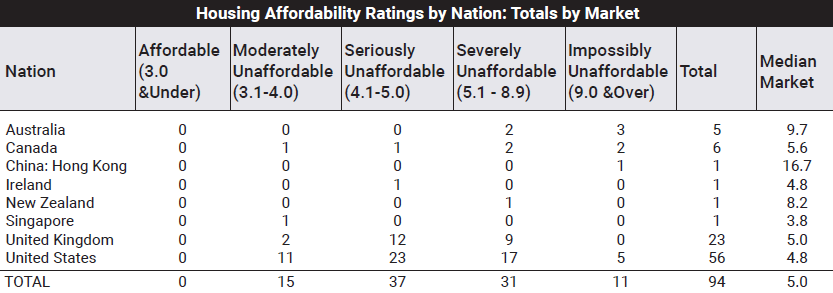

The report measures housing affordability on a median price-to-income ratio, or ‘median multiple’. Then it breaks housing markets down into categories, from affordable, down to impossibly unaffordable. A median multiple of 3x or under is deemed affordable, while 9x or over is considered impossibly unaffordable.

The report only introduced the category of ‘impossibly unaffordable’ this year to describe cities where housing purchases are extremely expensive relative to incomes, topping its previous highest category of ‘severely unaffordable’.

Source: Demographia International Housing Affordability 2024 edition

Here’s how Australia stacks up against seven other developed countries.

Source: Demographia International Housing Affordability 2024 edition

Australia’s five major capital cities, excluding Darwin, Canberra, and Hobart, are considered either severely unaffordable, with price-to-income ratios between 5.1x and 8.9x, or impossibly unaffordable, with median multiples of 9x or more. The median price-to-income multiple across the five cities is 9.7x.

The chart shows that Australia’s median multiple is more than 2x the US market of 4.8x or almost 2x the UK market of 5x. The US has five ‘impossibly unaffordable’ markets compared to Australia’s three, which shouldn’t surprise given the US has a population almost 13x greater than here. China, Hong Kong more specifically, is the only market that’s more expensive than Australia.

The other thing to note is there isn’t one city in any country which has a property market deemed affordable. Singapore is the most affordable market, though 78% of the population lives in public housing.

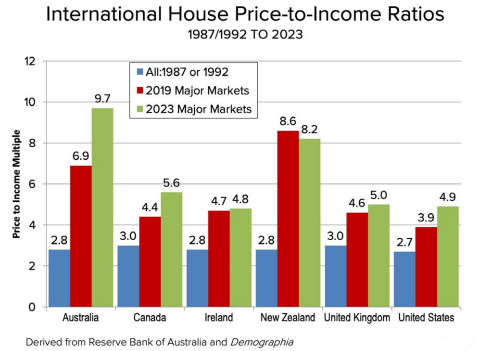

The next chart shows how house prices have exploded across all the countries over the past few decades.

The jump in the median multiple of Australia is something to behold. In 1987, the price-to-income ratio here was just 2.8x. Even in recent years, the multiple has also seen a tremendous uplift, from 6.9x in 2019 to 9.7x now.

The chart shows that back in 1987, every country’s housing was considered affordable, under a 3x median multiple.

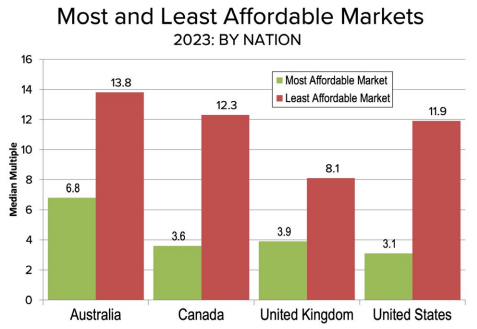

Other nations have seen an increase in their median multiple over the past four decades, yet Australia’s uplift has been the greatest by far. The report suggests that it isn’t just one city that’s making Australia unaffordable. Even our most affordable market is still well above other countries.

Source: Demographia International Housing Affordability 2024 edition

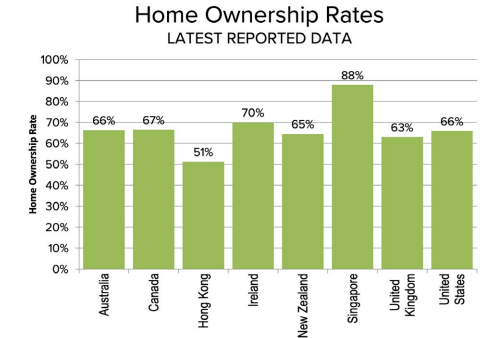

Home ownership rates don’t explain why Australia prices are so much higher than most. Our home ownership rate of 66% is about average across the different countries.

Source: Demographia International Housing Affordability 2024 edition

Drilling down into Australia

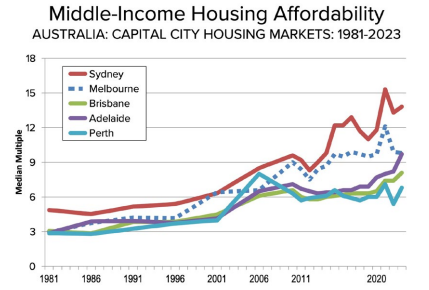

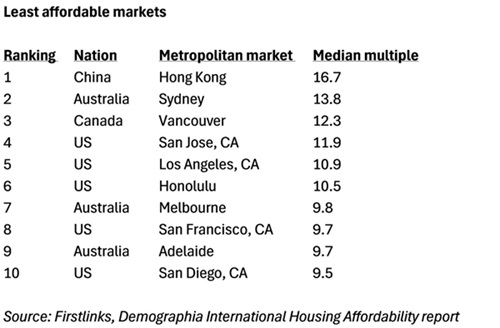

Sydney is the least affordable market in Australia, with a median price-to-income ratio of 13.8x. That multiple also makes it the world’s second least affordable city, behind Hong Kong. It’s not unusual for Sydney to be considered expensive on a global basis, as it’s been in the top three least affordable cities in 15 of the last 16 years, according to the report.

Source: Demographia International Housing Affordability 2024 edition

Melbourne is the second most expensive city in Australia, with a median multiple of 9.8x. Adelaide rounds out the list of Australia’s ‘impossibly unaffordable’ cities, with a median multiple of 9.7x.

Brisbane and Perth are less expensive, though still considered ‘severely unaffordable’, with price-to-income multiples of 8.1x and 6.8x respectively.

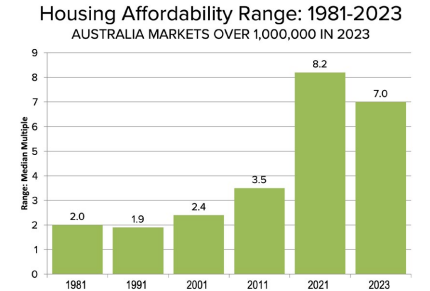

The report also notes that the gap in affordability between Australian cities has widened in recent decades. In 1981, the gap between the least affordable city and the most affordable was just 2 median multiple points, whereas today it’s 7.

Source: Demographia International Housing Affordability 2024 edition

Australia has three of the least affordable cities in the top 10.

Explaining the global rise in house prices

The report doesn’t hold back on the housing affordability crisis across the developed world. First, it suggests current struggles with high costs are rooted in high prices for housing:

“Middle-income households face rapidly escalating housing costs, which is the primary cause of the present cost-of-living crisis. For decades, home prices generally rose at about the same rate as income, and homeownership became more widespread. But affordability is disappearing in high-income nations as housing costs now far outpace income growth.”

As to a cause for higher house prices, the report is pointed:

“The crisis stems principally from land use policies that artificially restrict housing supply, driving up land prices and making homeownership unattainable for many.”

It says the solution to the crisis lays in increasing land supply:

“Urban containment policies (greenbelts urban growth boundaries, densification) are designed to limit sprawl and increase density. While well-intentioned, these policies severely constrict the land available for housing. In constrained markets, higher land values translate to dramatically higher housing prices…

The housing crisis demands prioritizing [sic] the well-being of people over abstract planning ideals. The planning orthodoxy, while aimed at improving cities, has worsened affordability. This undermines the economic opportunity essential for thriving middle-and lower-income households.”

The New Zealand experiment to making housing affordable

The report lauds New Zealand for its efforts to try to address housing affordability issues:

“New Zealand provides a hopeful path forward. Recognising the crisis is rooted in high land values, new policies are proposed to open up sufficient land to accommodate demand.”

The report’s applause for New Zealand’s policies is somewhat odd given these policies have primarily promoted greater medium-density housing – something that Demographia doesn’t favour to address housing shortages.

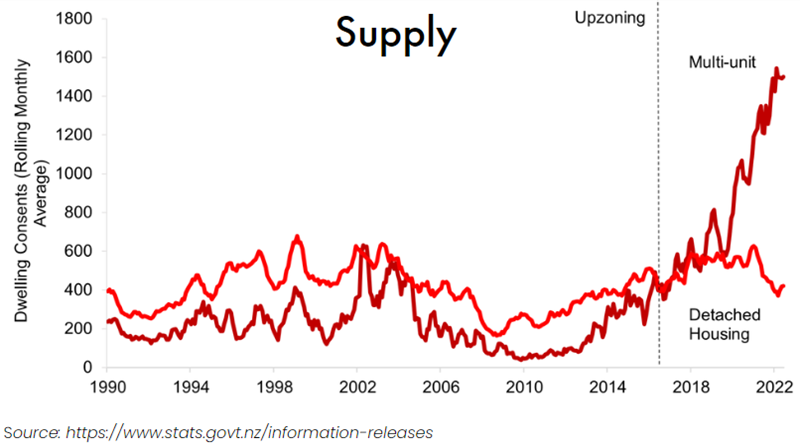

In 2016, Auckland upzoned about three-quarters of its residential land area under the Auckland Unitary Plan. In this case, upzoning meant abolishing single-family zoning to allow for multi-unit housing. It also involved changing zoning laws to allow high density housing around transit corridors.

The encouraging signs from the Auckland moves has resulted in New Zealand rolling out sweeping legislation to allow medium-density housing across all the country’s major cities.

So, how successful have the Auckland reforms been? It’s undoubtedly led to a large increase in new dwelling starts, most of which have been multi-unit dwellings. Academic studies show that the housing stock was 4% more than it would have been without the policies from 2016 to 2020.

The location and composition of builds has also changed. In 2015, two out of three housing permits were issued in the inner suburban areas. Five years later, the figure was 6 out of 7.

Interestingly, upzoned properties have increased in value in Auckland more than non-upzoned houses. That shows the market has ‘rewarded’ the upzoning option by ascribing it greater value.

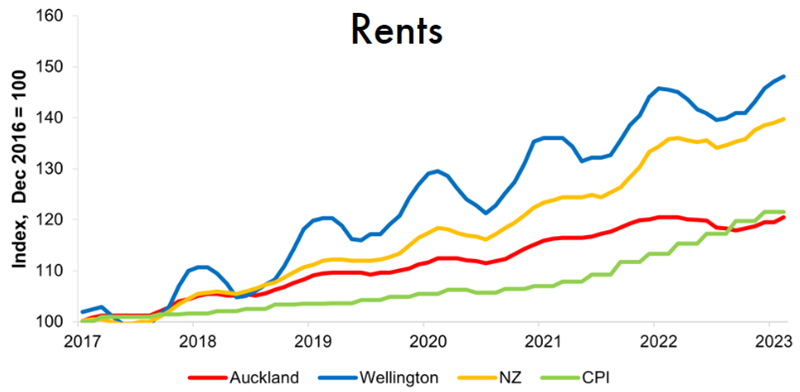

Meanwhile, rents in Auckland have declined in real terms since 2016. They trailed the rental growth of other major New Zealand cities by some way.

Source: https://www.tenancy.govt.nz/about-tenancy-services/data-and-statistics/rental-bond-data/

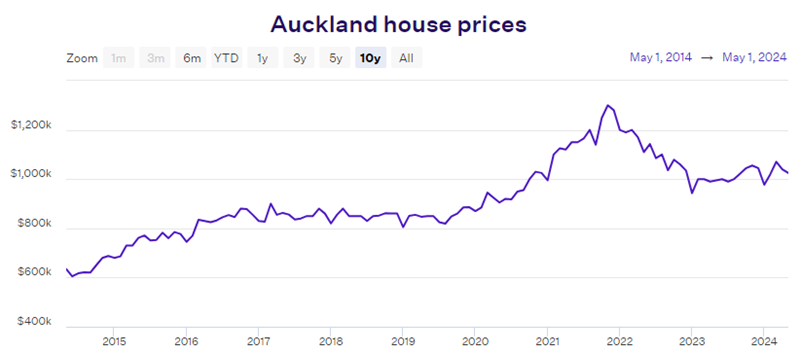

House prices in Auckland have fallen sharply since peaking at NZ$1.3 million in November 2021. However, the fall came after a tremendous increase during the pandemic.

Source: Opes Partners

The jury is still out on the success or otherwise of Auckland’s reforms. They’ve certainly increased supply and seem to have stabilised rents. Whether they’ve impacted house prices is open to debate. The pullback in Auckland’s house prices since 2021 has coincided with a large rise in interest rates, so it may not just be increased supply that’s caused these price falls.

A fuller picture will emerge in coming years as the zoning changes take effect across other cities.

James Gruber is an assistant editor at Firstlinks and Morningstar.com.au.