Shane Wright has given us another warning of the tax iceberg in the water dead ahead.

At the end of the day, the simple question is: What do we (as in our governments) do? Do we tax the rich, or do we cease many government services and support for the economy? And do we shift the tax base to more efficient and equitable sources, such as resources?

Shane Wright

June 27, 2024 — 10.30pm

The federal budget will forever be mired in huge deficits if future governments deliver tax cuts to working Australians without “substantial” spending cuts or tax increases worth tens of billions of dollars, the independent Parliamentary Budget Office has revealed.

The PBO has indeed revealed this, while the alarm over NDIS-related outlays has started to become punitive, with spending running at a rate suggesting it will rival military spending and pensions.

Advertisement

This comes against the backdrop of unemployment remaining pretty close to multigenerational lows. Then remind yourself that health centres are scrapping bulk billing because the Medicare subsidy isn’t keeping them in the game. And before you look away, catch a glimpse of the price tag on those shiny new bipartisan AUKUS submarines. The political questions are becoming louder when it comes to funding.

Ahead of new figures that are expected to show the current budget with a surprisingly large surplus before nose-diving into the red in 2024-25, the analysis by the budget office shows eradicating bracket creep would leave a hole in the budget that could climb to more than $85 billion a year.

And if the government fails to keep a lid on grants and departmental spending, public debt could climb by an extra $300 billion over the next decade and inflict even more pain on taxpayers.

That’s a pretty good sighting of two things. The first is that when those commodity revenues drop away, they are going to really drop away.

Advertisement

Globally, coal is in big demand, and our gas is in good demand too. The only problem is that we are selling dirt cheap to China, Japan, and Korea and they are selling with good margins further afield (treating us much the same way as our retailers treat vegetable growers or dairy farmers). However, iron ore is showing the way of the future for all of them.

We shouldn’t be surprised. This is what commodity markets do. Australia, however, has taken what we told ourselves would be the once-in-an-eternity mining boom resulting from a rising China and assumed that we never needed to do anything else. The curtain is coming down on that mindset.

The second issue the above brings to the fore is about what that curtain is coming down on.

Advertisement

If you are all about PAYE taxpayers, then Shane’s piece is all about conveying the idea that it is either your taxes or government spending.

Shane would have us thinking we can have the tax cuts to offset the bracket creep inflicting real pain in suburban Australia on families comprised of two average income earners. OR, we can have the services, the social supports, and the Submarines.

That may be true, but it brings about a load of questions before anyone should agree to it. And it leaves a lot of things unspoken, which is just the way the beneficiaries of those unspoken things like it.

Advertisement

Workers will share in $23 billion worth of income tax cuts from July 1, returning bracket creep that has built up over the past decade. Bracket creep is the increase in a person’s average tax rate as their income grows over time.

Parts of the Coalition are agitating for tax thresholds to be indexed to inflation to ensure people’s average tax rates are not increased. On Thursday, Liberal leader Peter Dutton said the Coalition had shown an appetite to deal with bracket creep while in government and that the value of next week’s tax cuts would be eroded “over a number of years”.

While indexing tax brackets has won some support among economists, Treasury secretary Steven Kennedy has warned it could make it harder to control inflation, putting pressure on the Reserve Bank to vary interest rates.

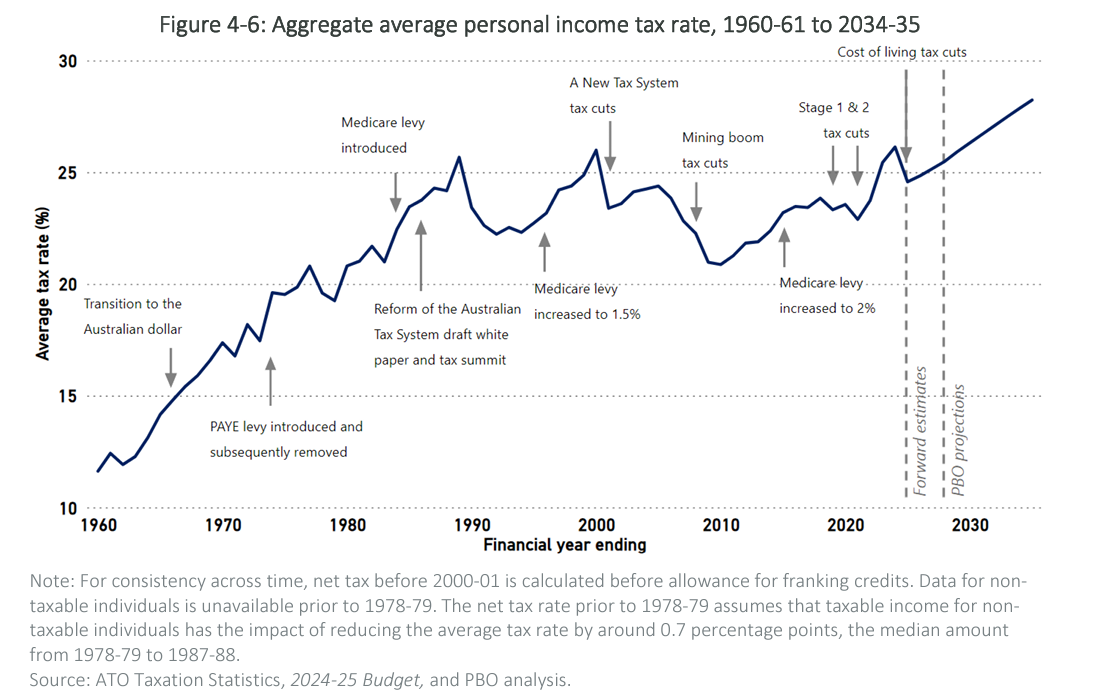

The budget office found that next week’s tax cuts will reduce the average income tax rate from 26.1 per cent to 24.6 per cent. But they will start to increase again from 2025-26 if tax thresholds are not adjusted.

At this point, the suggestion is that maybe the Liberals may push for some form of indexing tax thresholds to inflation.

Anyone who gives that much credence should remind themselves that the ALP government (for all of their faults) reworked a tax cut that their Liberal predecessors planned to give the lot to the top 10% of earners, which is the only reason workers will get the merest sniff of $23 billion in income tax cuts next week.

Advertisement

They may be serious. But the only reason the Liberals would go there is to nail government outlays to the floor while they are in opposition. This would give them more credence as an alternative government in the lead up to a federal election, or give them a plausible starting point to hack away at outlays should they ever return to power.

All of this avoids examining the utterly nefarious range of tax concessions Australia hands out. It also distracts from conducting a root and branch overhaul of Australia’s taxation system and its relationship to the economy.

Those driving the national economy can continue to do burnouts in the suburbs as braking or accelerating requires.

Advertisement

Without change to the personal tax system, the budget – forecast to record a $28.3 billion deficit in 2024-25 – would eventually move back into surplus in 2034-35.

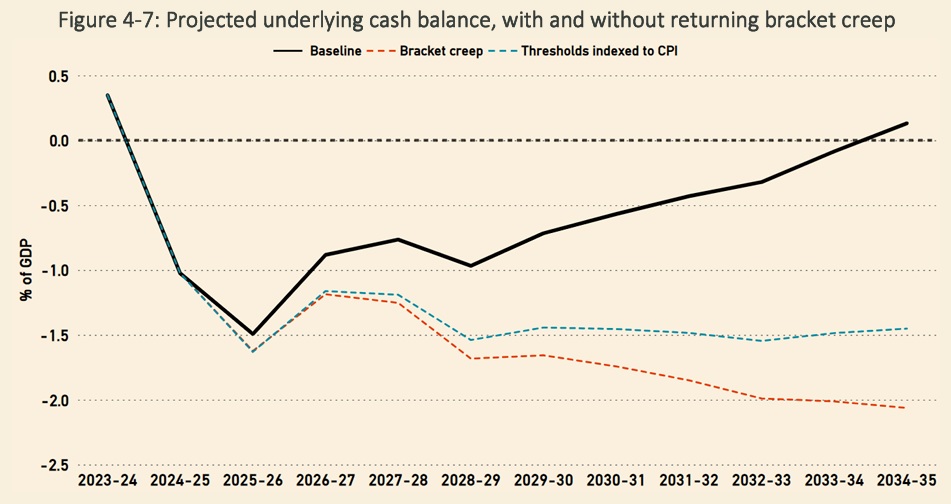

But if thresholds moved in line with inflation, the budget would show a deficit of 1.5 per cent of GDP – or about $60 billion – by 2035. If thresholds moved with wages, the deficit would be around $85 billion.

“In both scenarios, the budget would never return to surplus, meaning that future governments cannot afford to fully compensate taxpayers for bracket creep without increasing other taxes or substantially cutting spending,” the budget office noted.

The point is now laid on with a trowel. If there is no change to the tax system, by 2034-2035, we will be back in surplus. But has there ever been a 10-year period without changes to taxation? Does anyone have reference to any 10 year budget position forecast that has ever been within a bull’s roar of being true?

In the Ninefax piece, they use a Ninefax version of this chart from the PBO:

Advertisement

That does support the message Shane is trying to convey. If we don’t change the PAYE settings from here, then ceteris paribus, Australia will make its way back into budget balance in 10 years time.

But if we address bracket creep and/or link it to CPI inflation, we won’t get there. But the PBO report has a load more charts worth looking at, starting with this one about average personal income tax.

Advertisement

That chart tells us that average personal income taxes are about to head higher than ever.

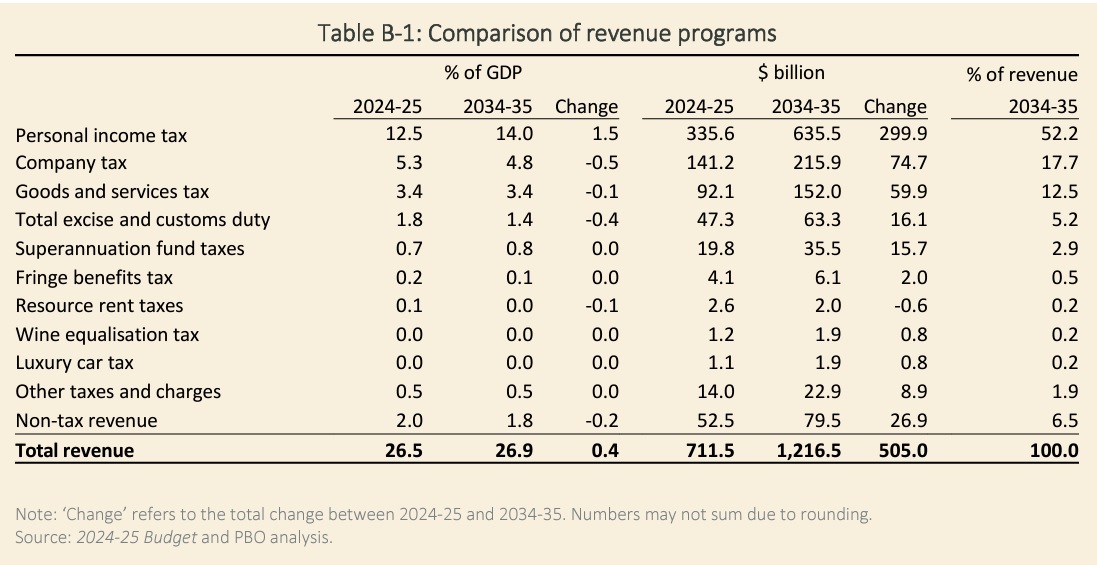

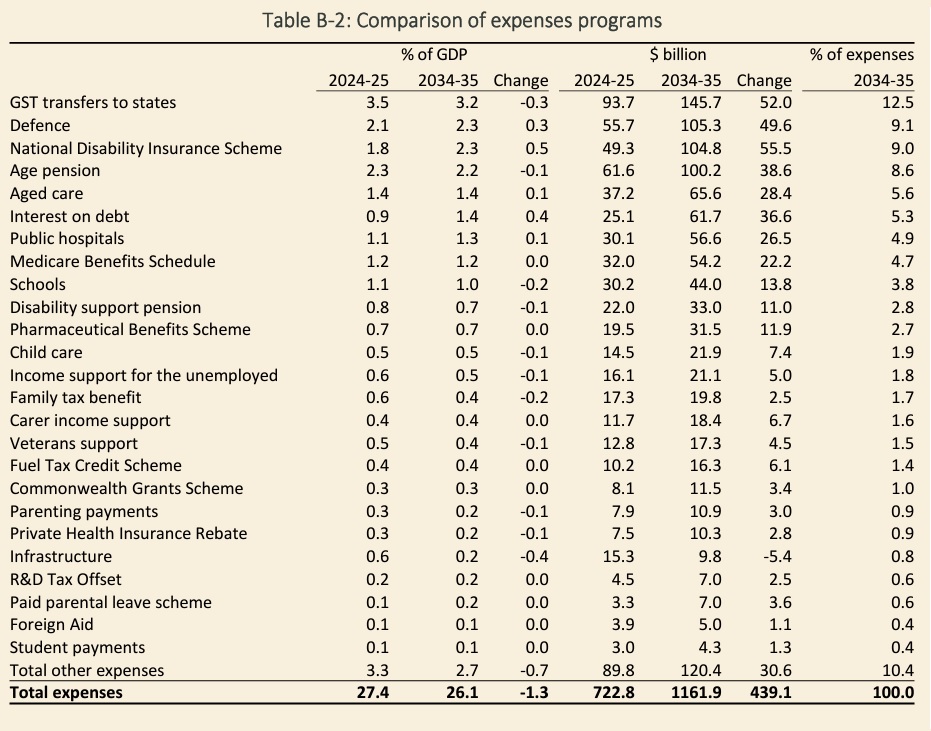

But there are also other charts which are every bit as interesting, particularly for those who don’t give that much thought to where and how the taxation system harvests us for revenues and what the proceeds go towards. These are well worth thinking about.

Advertisement

But even these tables don’t properly convey several key factors in Australia’s dynamic. But lets go back to Shane for reportage on what the above charts make clear.

Advertisement

Personal income tax already accounts for half of all revenue raised by the federal government. This will grow as other sources of cash recede.

The budget office noted excise revenue, which in the early 1980s accounted for a quarter of all tax, is on track to fall to just 5 per cent of total Commonwealth collections by the middle of next decade.

The advent of electric vehicles and more efficient petrol-driven cars is expected to reduce fuel excise, which the budget office projected could be between $2.8 billion and $4.8 billion a year lower by the mid-2030s.

Tobacco excise could collapse to little more than a rounding error, while alcohol excise could also fall.

“Together, the most extreme downside scenarios would result in excise being lower by $12 billion by the end of the decade,” the budget office found.

“As the tax base narrows our reliance on personal income tax increases. Government revenues become more sensitive to both changes in the composition of the economy and future policies to compensate taxpayers for the impact of bracket creep.”

Government spending is expected to ease slightly over the coming years, mostly due to smaller grants to states and territories for major infrastructure projects.

The fastest growing expense is interest on federal government debt and the National Disability Insurance Scheme.

But the budget office warns that spending on government departments and grants programs has been consistently underestimated. If this were to continue, the budget would be $50 billion worse off in 2034-35 while the government would be carrying $300 billion in extra debt.

All superbly plausible and likely fairly accurate. Then comes the conclusion, that PAYE income tax payers will get hosed.

In the short term, Treasurer Jim Chalmers will receive some good news on Friday, with monthly figures expected to show a sharp but temporary improvement in the budget.

In May, Chalmers forecast a surplus of $9.3 billion for the current financial year. To the end of April, the budget was showing a surplus of $300 million, but this is expected to have been inflated by large corporate tax collections over the past month.

It may not last long with extra expenses in June likely to bring the overall surplus down to around its May forecast.

“Whatever the final result, it’s already clear that delivering back-to-back surpluses for the first time in nearly two decades is the right thing for our economy, for interest costs in the budget, and as a buffer against global uncertainty,” Chalmers said.

Advertisement

That is all well and good, after the policy lacunae and brain farts of the last 20 years. But a few more charts add important context.

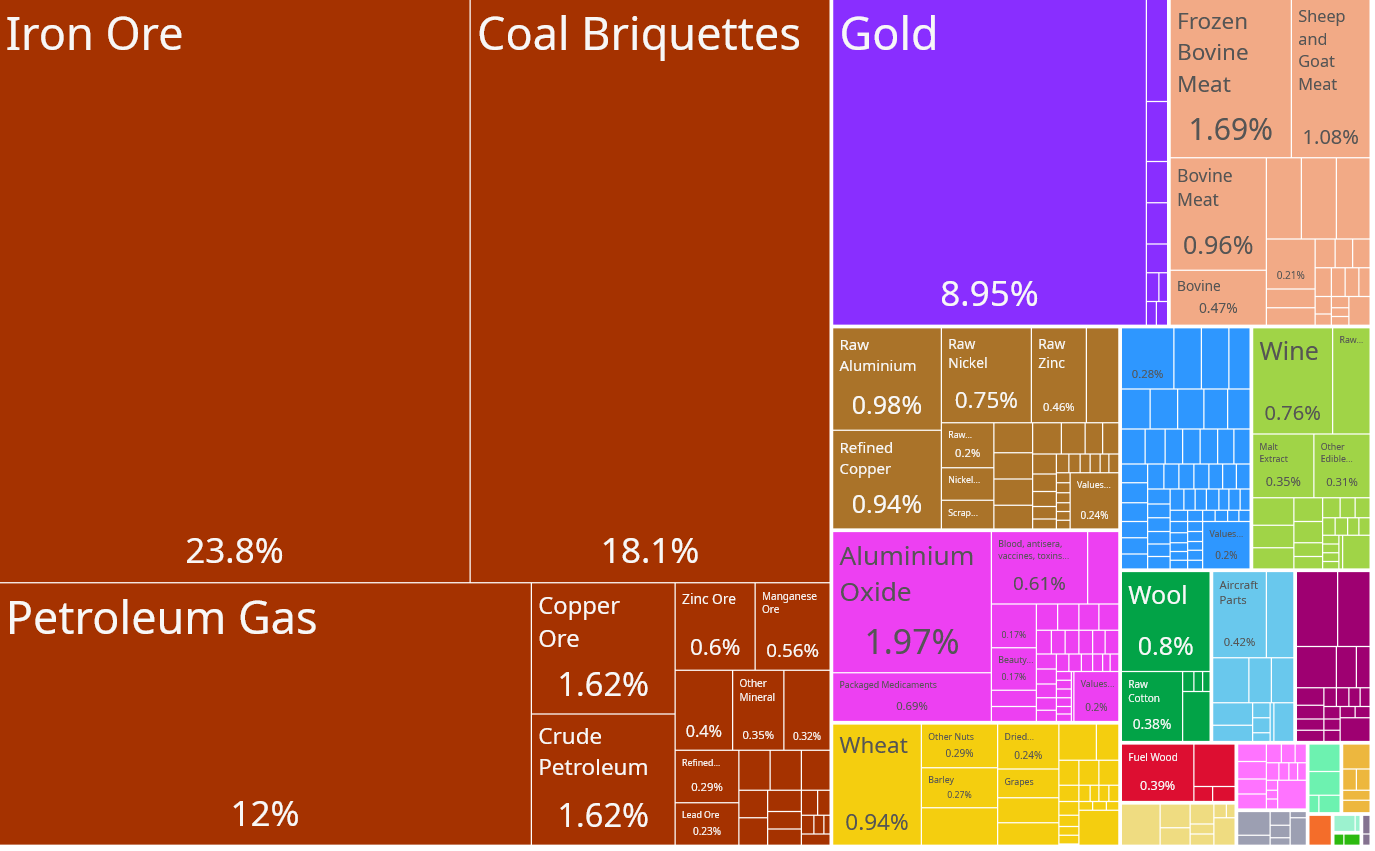

The first is the following chart showing Australia’s exports:

The above chart tells us that raw commodities dominate.

Advertisement

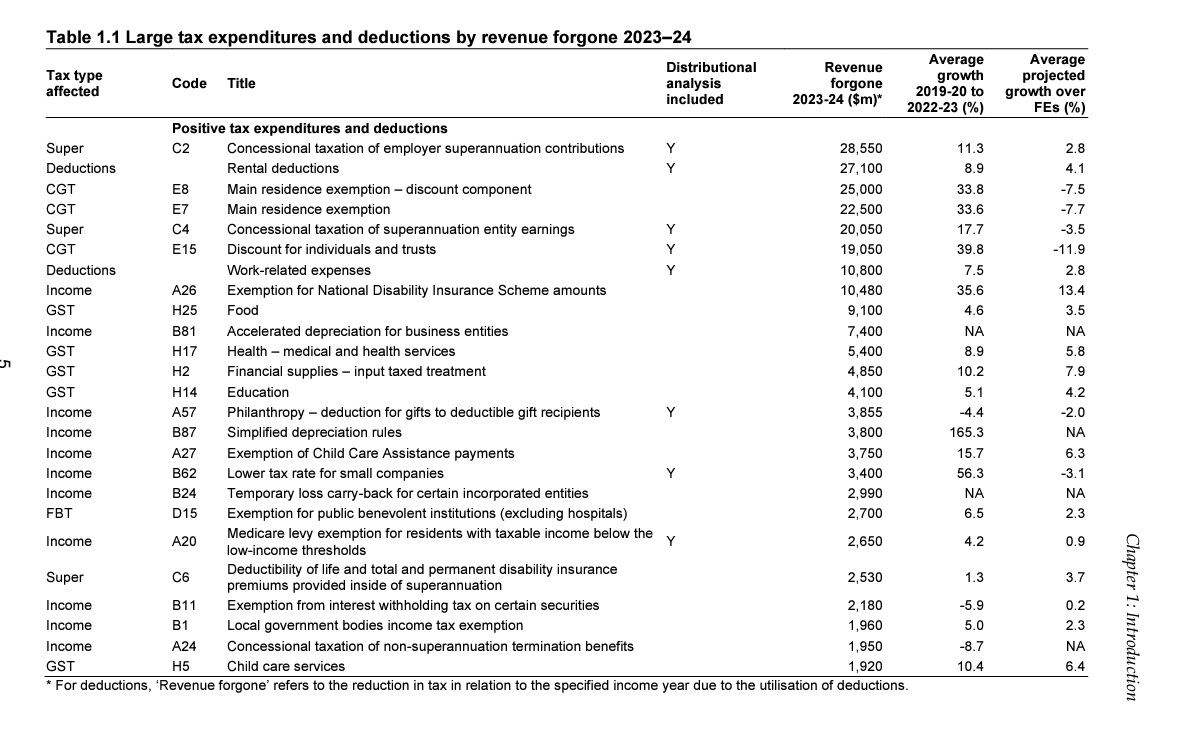

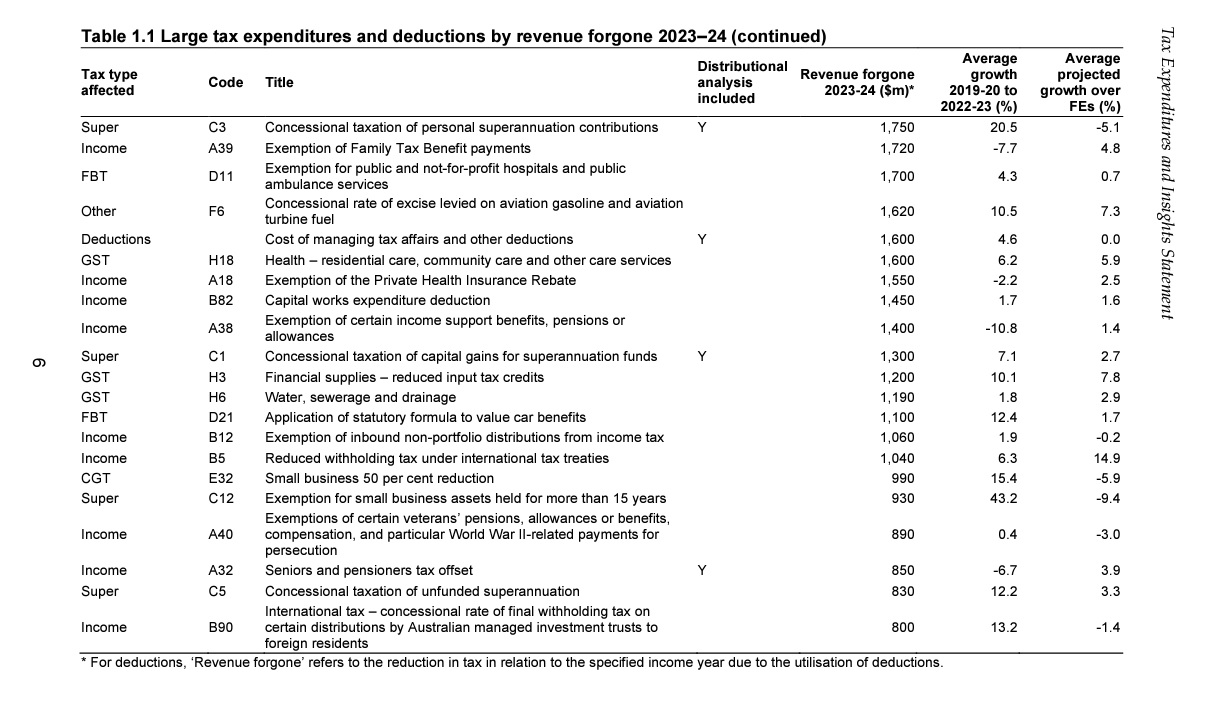

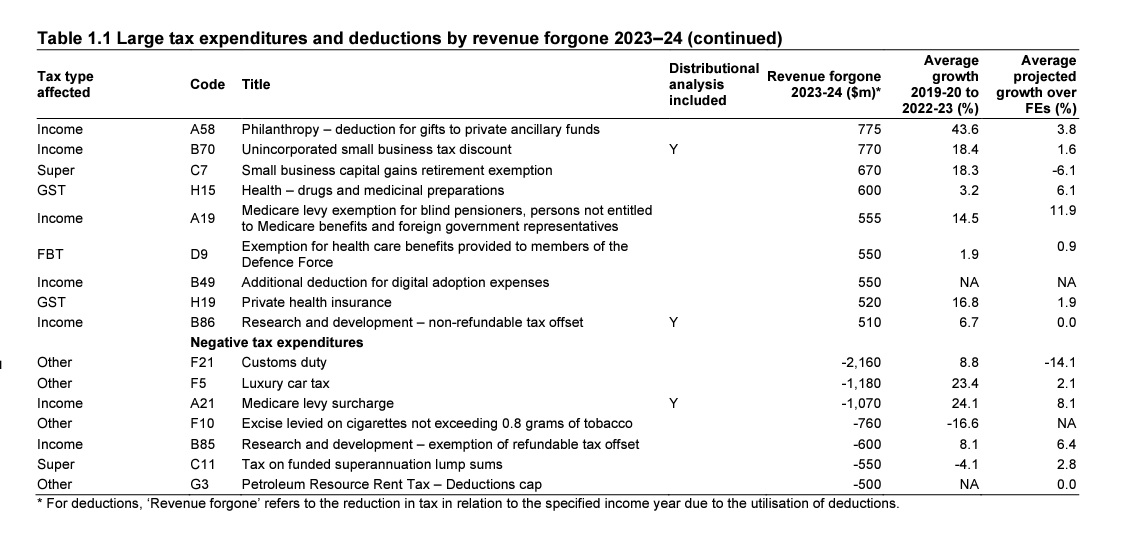

The other set of charts worth considering are tax concessions (2024 version from January linked), which include the following:

Advertisement

The above are concessions which enable reductions in other taxes.

If Australia is setting forth into a future where its current income-generating sectors are sliding beneath the waves and we are going to need to harvest the people working to fund the activities of the Federal Budget (and also state budgets), then we urgently need to ask ourselves a few questions.

If we set aside the first as being ‘How did we so totally stuff up the last 20 years?’ and just accept that we need to get our focus on the future and the lives of our children, those questions become:

Advertisement

- How do we become competitive at doing something other than importing people?

- What structural factors (housing costs, energy costs, land costs, internet costs, education transport bureaucracy, etc) restrict our competitiveness?

- Do our tax concessions help us to become more competitive or are they simply tax avoidance mechanisms of the more affluent beneficiaries of the government funded bubble we currently operate?

- Is having a tax system increasingly reliant on personal income taxes efficient and equitable?

- Why isn’t Australia capturing more benefits from its enormous mineral endowment and exports via the tax system, as clever nations like Norway do?

No matter how much we may want to simply tamper with the settings of the economy, the entire system needs fundamental reform.