A new Australian study has found that early exposure to the influenza B virus impacts how well a person’s immune system can recognise new variants and protect against them later in life.

The findings indicate that individuals develop a stronger immune response to variants of influenza B (IBV) they were exposed to in childhood. As a result, their body will exhibit a stronger immune response for newer influenza B variants that share similar characteristics with strains that were circulating during their first 5 to 10 years of life.

The research provides strong immunological evidence to support previous epidemiological studies which found differences in susceptibility and severity of influenza infections based on year of birth.

Researchers analysed more than 1,400 serological samples collected from individuals born in Australia and the United States between 1917 and 2008. They measured the antibodies present in the samples and compared them to the IBV strains circulating globally between 1940 and 2021.

“Using this comprehensive dataset, we discovered that the highest concentrations of antibodies in each sample generally corresponded with the dominant strain of influenza B virus that was circulating during that individual’s childhood,” says first author Peta Edler, a research assistant in biostatistics at the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity at Australia’s University of Melbourne.

“Essentially, when it comes to influenza B virus infections, first impressions matter. The initial, early-life exposure to the virus appears to influence how the immune system responds to future influenza B viruses.”

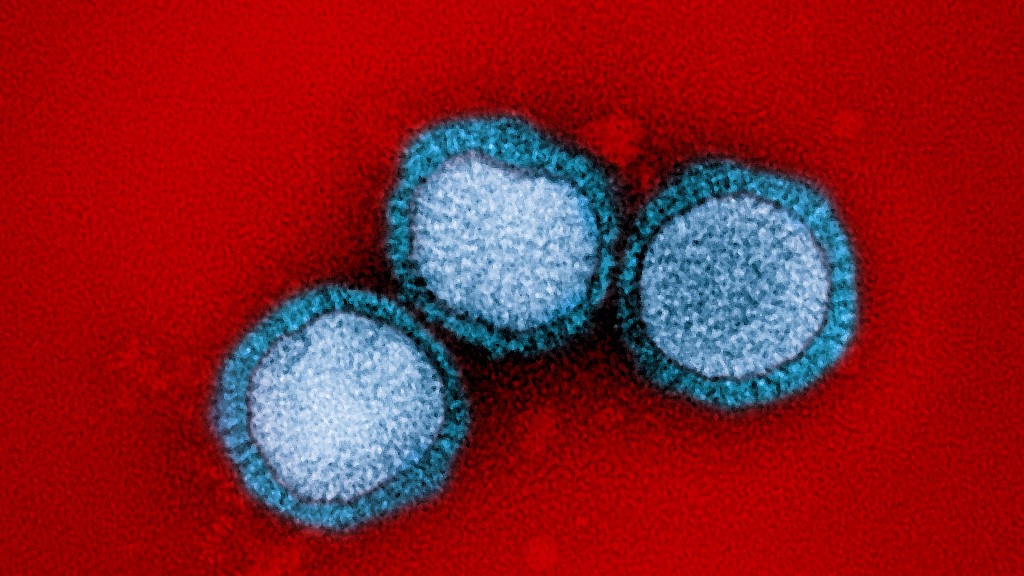

Influenza B viruses belong to either the B/Yamagata or B/Victoria lineages. They account for a substantial proportion of annual influenza cases and are the prominent circulating subtype of influenza every 4 to 5 years.

“In the first 3 decades since its discovery in 1940, IBV circulated as a monophyletic lineage, referred to as ‘Ancestral’,” the authors write in the study, which is published in Nature Microbiology.

“In the early 1970s, a lineage (later designated as B/Victoria) appeared that was antigenically distinct from Ancestral viruses.

“In the 1980s, a second antigenically distinct lineage emerged (designated as B/Yamagata), which predominated in the 1990s, with B/Victoria remaining confined to low levels within Asia.

“Subsequently, the B/Victoria lineage re-emerged globally, and the two lineages co-circulated from the early 2000s until the putative extinction of B/Yamagata in 2020.”

According to Marios Koutsakos, a Doherty Institute senior research fellow who led the study, establishing an immunological link between initial exposure to influenza B and long-term immune responses opens new pathways for vaccination and the public health response to manage risks.

“Our research could help predict which populations are most at risk of disease during each flu season, which would guide the development of public health strategies targeting specific age groups,” says Koutsakos.

“Moving forward, we want to explore what drives this long-term immunity and find out whether our immune system behaves the same way following its first exposure to influenza A.

“This work could uncover potential targets for the design of new vaccines, but also inform tailored immunisation strategies.”