Characteristics of studies

Our database searches identified 3,935 records and our manual searches 38 records, of which 1,910 were duplicates. We screened the titles and abstracts of 2,063 studies, deeming 1,908 irrelevant. We screened the full texts of 155 studies, with Fig. 1 detailing reasons for exclusions. In the end, we included 14 studies. When screening abstracts and titles, Cohen’s kappa ranged from κ = 0.46 to κ = 1 across reviewer pairs; when screening full texts, it ranged from κ = 0.71 to κ = 0.81 across pairs.

Nine of the 14 included studies were NRSIs [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39] and the rest RCTs [12, 40,41,42,43]. All nine NRSIs were uncontrolled trials. Coding was generally straightforward, though some data points such as percentage of females in the sample were sometimes missing in manuscripts. Together, studies included 286 participants with individual study sample sizes ranging from 4 to 42 participants (x̄ = 20.43, s = 11.58, x̃ = 20). Attrition rates ranged from 0 to 94% (x̄ = 21.39%, s = 21.56%, x̃ = 16.50%). Based on guidance, we classified 86% of these studies as feasibility studies, since they included fewer than 25 participants in total, or fewer than 25 participants per group [44].

Figure A, Figure B, and Figure C provide a tabular summary of included studies, but we also provide below a prose summary. Participants’ age ranged from 19 to 100 years (x̄ = 75.45, s = 12.89, x̃ = 77.55). Only two studies reported inclusion of participants younger than 50 years [12, 32]. A third study is likely to have included them [36]. Nevertheless, none of the three studies focused on participants younger than 50 years exclusively, and hence studies only included young participants along with older ones. Remaining studies explicitly reported excluding those younger than 50 [31, 33, 35, 37, 38, 40, 41, 43] or their sampling frames implied this [34, 39, 45]. Where reported, the percentages of both females and non-White participants were high in most studies.

Nine studies used social robotic relational agents [31,32,33,34,35, 39, 41, 43, 45] and five app-based relational agents [12, 36,37,38, 40]. The social robotic agents included Sony’s AIBO [32, 34, 41], PARO developed by ISRI [31, 33, 45], NAO developed by Aldebaran Robotics [35], Pepper developed by SoftBank Robotics [43], and either a robotic cat or dog developed by Joy for All [39]. The app-based agents included Laura developed by MIT [40], Elena + developed by ETH Zurich and the University of St. Gallen [36], Amazon’s Alexa [37], Bella by Soul Machines [46], and PACO developed by a consortium of Dutch organisations [38]. The relational behaviours of these agents varied. AIBO is a robotic puppy, PARO a robotic seal, and together with the robotic pets by Joy for All, these agents simulated live pet behaviour (e.g., the agents expressed emotions via facial cues and body language such as wagging of tails, played with users, learned their own names, and recognised users via their facial recognition capabilities) [32]. The agents responded to touch (e.g., petting) and adapted behaviour through reinforcement learning [33]. NAO and Pepper were humanoid robots that simulated human behaviours, customs, and speech. NAO, for example, would bow to users, extend its palm for a handshake, ask if participants would want to hear a poem, and only proceed once receiving a reply [35]. All app-based relational agents simulated humans. All were embodied, i.e., had a visual form, except for Amazon’s Alexa [37]. App-based agents primarily or to a significant degree used speech for relational behaviour. Laura, for example, expressed empathy (“I am sorry to hear that”), asked follow-up questions (“How tired are you feeling?”), and attempted to get to know users (“So, are you from the East Coast originally?”) [40]. Whilst in previous research several agents used “wizard-of-Oz methodologies”, i.e., agents controlled by humans pretending to be autonomous, all agents in this review were autonomous [47].

Most relational agents in our review acted as direct companions and did not seek to mitigate loneliness via other modalities [31,32,33,34,35, 37, 39,40,41, 43, 45], although exceptions existed. Elena + sought to remove cognitive biases and improve social skills [36]. PACO sought to create opportunities for socialising [38]. Bella sought to enhance social skills, increase social support, and increase opportunities for socialising [12].

Studies generally did not mention behavioural theories or behavioural change techniques (BCTs) that underpinned intervention design, although exceptions existed. One study based its intervention on Self-Determination Theory [38] and another study based its intervention on the COM-B model and the Theory of Planned Behaviour [36]. Nevertheless, these studies provided little detail on how exactly theories informed design. We classified BCTs according to the BCTTv1 by Michie et al., using below in quotation marks the labels of the original authors [48]. Only one study confirmed the full range of BCTs it used, and two other studies provided examples of BCTs. One study used six BCTs: “credible source”, “review behaviour goals”, “goal setting”, “instruction on how to perform a behaviour”, “social comparison”, and “social support” [38]. Another study mentioned seven BCTs: “information about emotional consequences”, “action planning”, “behavioural contract”, “instruction on how to perform a behaviour”, “review behaviour goals”, “reducing exposure to cues for the behaviour”, and “reduce negative emotions” [12]. A third study mentioned five BCTs: “information about emotional consequences”, “goal setting”, “instruction on how to perform a behaviour”, “reducing exposure to cues for the behaviour”, and “reduce negative emotions” [36].

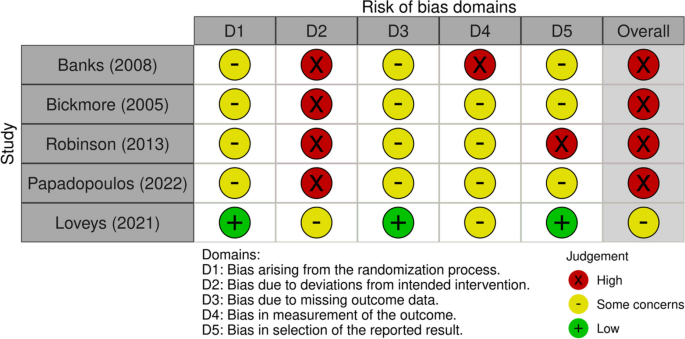

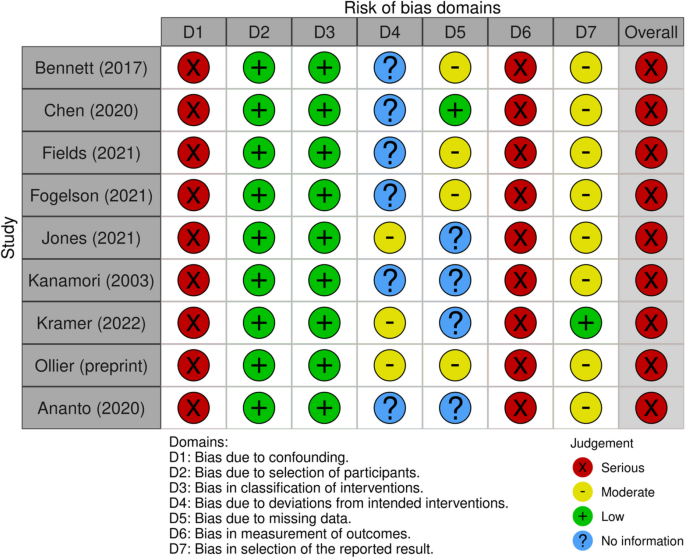

All RCTs were at high risk of bias due to potential deviations from the intended interventions [40, 41, 43, 45] except for one [12]. All NRSIs were at high risk due to confounds and potential biases in measurements [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Figures 2 and 3 illustrate these.

Meta-analysis

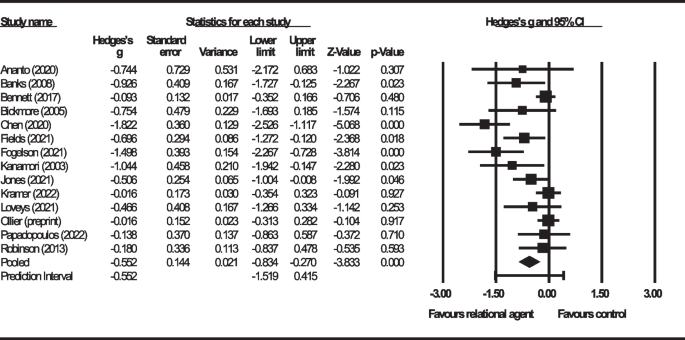

The pooled estimate of Hedge’s g was -0.552 (Z = -3.833; 95% CI, -0.834 to -0.270; P 4. Using a Bonferroni-corrected αBonferroni = 0.0125, there was evidence to reject the null hypothesis. Using the Knapp-Hartung adjustment, there was also evidence to reject the null hypothesis (t = -3.66; 95% Knapp-Hartung CI, -0.877 to -0.226; P = 0.003).

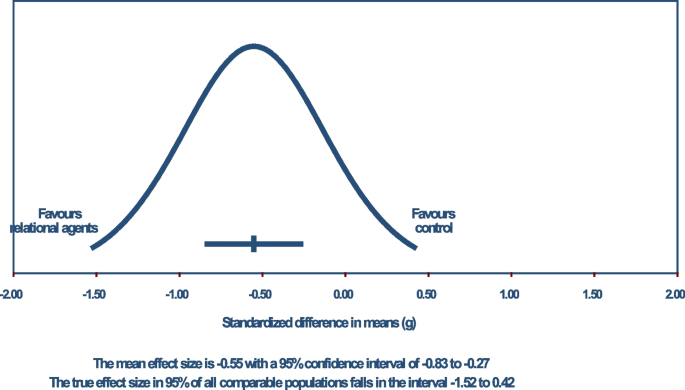

Heterogeneity measures indicated that, as anticipated, the true effect of relational agents varied (Q = 45.073; I2 = 71%; τ2 = 0.176; τ = 0.420). Assuming a Gaussian distribution, the 95% prediction interval was estimated to range from -1.519 to 0.415, as seen in Fig. 5.

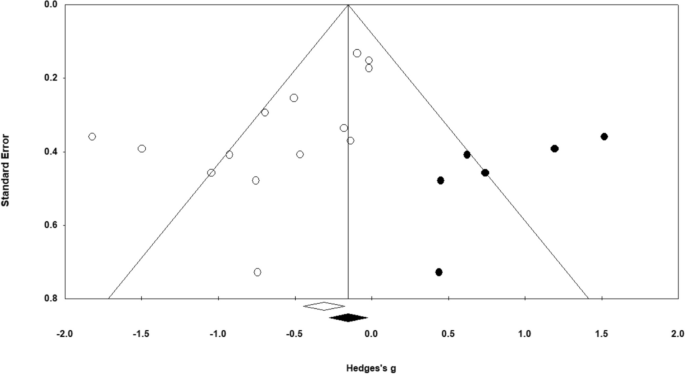

Funnel plots as well as Egger’s test (b = -2.81; t = 3.5; P = 0.004) suggested that a small study effect may exist. Figure 6 illustrates this. The small study effect could have been due to effect sizes being larger in smaller studies or due to publication bias. Assuming a severe publication bias, the trim-and-fill algorithm resulted in an adjusted estimate of g = -0.198 (95% CI, -0.505 to 0.109), which attenuated the original estimate by roughly 64%.

Five studies were available for the RCT-only model. Hedge’s g was -0.437 (Z = -2.495; 95% CI, -0.781 to -0.094; P = 0.013), which was 21% less than the estimate of the main model. The results were significant at a traditional α = 0.05 but not at the αBonferroni. The Knapp-Hartung adjusted results were not significant (t = -2.49; 95% Knapp-Hartung CI, -0.924 to 0.049).

Six studies were available for the app-based relational agent model. The pooled estimate of Hedge’s g was -0.286 (Z = -1.611; 95% CI, -0.553 to -0.020; P = 0.035), which was significant at a traditional α but not αBonferroni. The Knapp-Hartung adjustment resulted in non-significant results (t = -2.11; 95% Knapp-Hartung CI, -0.636 to 0.063). Eight studies were available for the social robotic relational agent model. The pooled estimate of Hedge’s g was -0.774, which was significant at αBonferroni (Z = -2.909; 95% CI, -1.296 to -0.252; P = 0.004). Using a Knapp-Hartung adjustment, results were significant at a traditional α but not at αBonferroni (t = -2.91; 95% Knapp-Hartung CI, -1.403, -0.145, P = 0.023).