Your Guide to KC: Star sports columnist Vahe Gregorian is changing uniforms this spring and summer, acting as a tour guide of sorts to some well-known and hidden gems of Kansas City. Send your ideas to vgregorian@kcstar.com.

On my way to the National Museum of Toys and Miniatures for the first time, my thoughts wandered to a “Seinfeld” episode in which Jerry becomes obsessed with a woman (Celia) because of her … vintage toy collection.

As they enter Celia’s apartment and she speaks of her father’s agonizing death, Jerry is mesmerized by her shelves of toys and proclaims, “Super Ball! Hey, the original G.I. Joe … with the full frogman suit.” When she takes offense, it’s not to Jerry’s jarring insensitivity but to his inclination to paw the priceless curios that never had been played with.

Not to say I wasn’t intrigued by the miniatures aspect of the museum. Hey, I drive a Mini Cooper and love Paul Rudd’s scale-shrinking Ant-Man character. But the enduring juvenile Seinfeld in me was most compelled by the prospect of revisiting childhood wonders.

Little did I imagine that the miniatures would make for the most indelible part of it all.

‘I wish I could bottle the energy’

Not that the toys weren’t enthralling; a wave of yesteryear rushed through me as soon as I entered that corridor of the intimately familiar in this delightful museum.

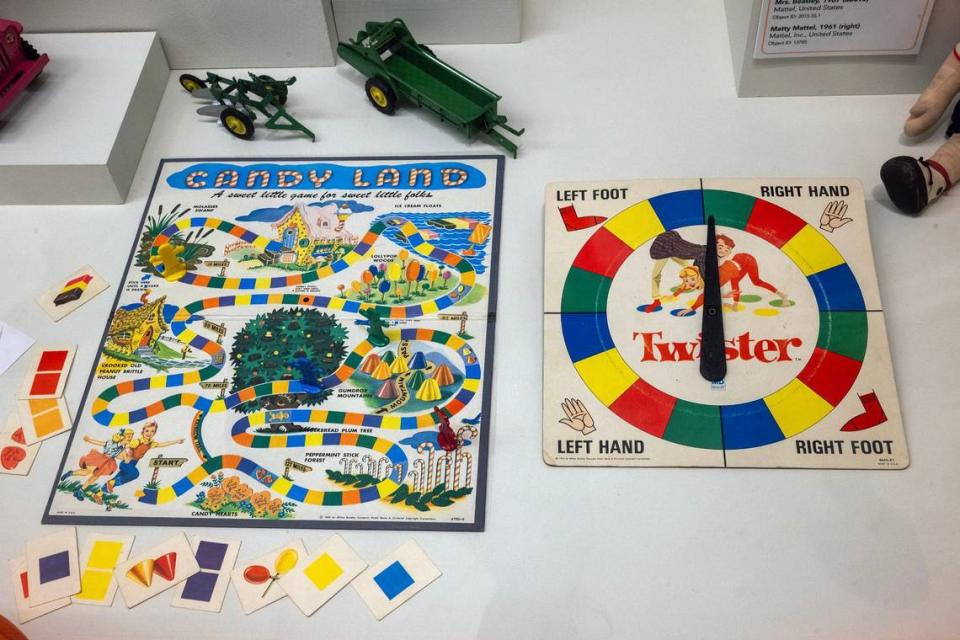

As a child of the 1960s, that was items like the Etch A Sketch, Hot Wheels tracks and a Magic 8-Ball. And games such as Battleship, Candy Land, Clue, Concentration, Monopoly and Operation.

And even though it didn’t have the obscure and modest marble chute that somehow forever amused my brothers and me or display that absurd old electric football game, it features a far more sophisticated and mesmerizing Rube Goldberg-esque version of marbles on the move and has in its collection but not currently on display a 1950s version of electric football — perhaps the very one I have in my home office.

Along with, as a matter of fact, G.I. Joe and Wham-O’s Super Ball — which, incidentally, in the mid-1960s inspired Chiefs founder Lamar Hunt to broach “Super Bowl” as the name for what initially was to be called the “AFL-NFL World Championship Game.”

That’s the sort of spontaneous talking point among friends and family that the museum encourages through this looking glass back to our childhoods.

“I nicknamed this our ‘multi-generational communication hallway,’” said Amy McKune, the museum’s curator of collections. “I wish I could bottle the energy that’s happening in here with visitors when they’re looking at toys from a different era and talking about their own toys.”

The unique appeal of the toy section, which along with the astounding doll and dollhouse collection is on the second floor of the museum at 5235 Oak St. on the University of Missouri-Kansas City campus, goes beyond simple nostalgia.

It’s also in how they are presented, including a touching and thought-provoking section called “Toys From the Attic” that highlights seven vital impacts of toys in our lives: comfort, relationships, learning to be a grown-up, values, learning through play, the world around us and imagination.

Prominent at the start of that section is the teddy bear of Mabel Dickson (1900-1981), whose parents died when she was less than a year old. Growing up with her maternal grandparents in Andrew County, Missouri, her teddy bear stood by her side even as she habitually punched it in the nose when she was frustrated.

“Despite her harsh actions,” the accompanying placard reads, “Mabel’s bear was a much-treasured companion and remained with her for the rest of her life.”

In several ways, that’s a telling snapshot of the museum’s toy department — a term we drop fondly because of its history of being applied to newspaper sports departments.

It encourages collection donors to share not only the objects but the stories behind them.

And, unlike Seinfeld’s Celia, it values the well-weathered toy more than the pristine.

If somebody came in offering a perfect-condition doll vs. one with disheveled hair or stains on it, the museum wants the latter every time.

“They loved it; they played with it,” said Madeline Rislow, a museum curator and senior manager of learning and engagement. “They have stories of it. Maybe they have photographs of them with a doll.”

‘You’re going to have to start a museum’

Speaking of dolls, the toys share the second floor with the enchanting collection of dolls and dollhouses, including the mind-boggling Coleman Dollhouse.

Built in the 1860s with functioning plumbing and gas lighting, the dollhouse stands more than 9 feet tall, 8 feet wide and 4 feet deep.

That dollhouse, one of some 275 in the collection, is an apt reflection of the spirit of Mary Harris Guinotte Francis, who along with Barbara Marshall founded the museum in 1982 at least in part at the apparently playful suggestion of Francis’ mother.

(This gift to Kansas City extends the considerable legacy of their families here: Marshall, who died in 2021 at age 97, was the daughter of Hallmark founder Joyce Hall and his wife, Elizabeth; Francis, who died in 2005 at age 78, was a descendant of Joseph and Aimée Guinotte, a founding family of Kansas City.)

After Francis and Marshall returned from one of their many trips fueled by Francis’ passion for dolls and dollhouses and Marshall’s zeal for fine-scale miniatures, Francis’ mother said, “If you girls get one more thing, you’re going to have to start a museum.”

“And Mary Harris and I kind of looked at each other and said maybe we would,” Marshall said with a smile in a museum video.

And so they did, creating a Kansas City treasure — also initially furnished with the toy collection of Jerry Smith — that still seeks to honor their long-cultivated visions.

As told in a congressional proclamation by U.S Rep. Emanuel Cleaver II honoring the 40th anniversary of the museum, Marshall’s interest in miniatures went back to at least the 1950s when she received as a gift from her father a rocking chair that fit in the palm of her hand.

Harris had acquired her first antique dollhouse in 1974. As it sat in a crate in her driveway, she told her husband “I’ll never need another.”

Instead, that proved a launch point for a woman well-remembered for having “never lost her child’s sense of play and imagination,” as described in her obituary.

That meshed well in her friendship with Marshall, who reveled in sharing her collection and frequently could be found around the museum as if a docent.

‘They’re saving history’

While the dolls and dollhouses and toys are in themselves riveting, what makes the museum an overwhelming delight is the fine-scale miniatures said to be the largest such collection in the world.

You can get a feel for the impossibly intricate and ornate work through the video on the homepage of the museum’s website, toyandminiaturemuseum.org.

It takes you through several displays that you can hardly distinguish from actual size … until a seemingly Brobdingnagian face or hand or implement invades the setting.

Still, the miniatures have to be seen to be appreciated for their ingenious artistry and jaw-dropping delicacy of the work.

Most are created on a 1-to-12-inch scale, but some are as infinitesimal as 1 to 48.

Not only is it hard to comprehend the patience any such endeavor requires but the craftsmanship also typically reflects exhaustive historical research.

“So it gives you a whole new way to look at historical elements or spaces that you can’t go visit anymore,” said Rislow, an art historian. “And these artists, I’m always astounded by how much they research and how much they look at photographs, drawings, testimonials … (and) inventory records for a space.

“And then they’re putting those elements together. And they’re opening it up in a completely new way that you can’t experience otherwise. So they’re saving history.”

As an Italian Renaissance specialist, she is most moved by the miniature replica of the Studiolo Gubbio, an Italian Renaissance room now found at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Reflecting the frequent collaboration among fine-scale miniature artists, it was created by four artists in four countries.

With some 22,661 miniatures and 70,358 toys in its total collection, about half of which aren’t currently on display, even the highlights are too vast to list here.

But what most resonated with me was on the first floor, starting with the two-story revolving spiral of toys known as the “Toytisserie.” The toys were donated by Kansas Citians during the 19-month renovation of the museum before it reopened in 2015, arranged in scenes by local artist Sarah Lugg Regan.

Reminiscent of a rotating barber shop pole, the sight makes for what Rislow jokingly called a “yield sign” for those who might want to rush up the stairs to the toys, only to be given pause to check out the miniatures — many of which were commissioned by Marshall.

By the time I was done on the first floor, it was easy to see why McKune says people are often surprised to suddenly have spent hours there and left with not enough time to enjoy the toys upstairs.

From the Masterpiece Gallery to the Miniature Art Museum to the Art Deco Jewelry Shop, from Kansas Citian William R. Robertson’s Twin Manors, nine years in the making, to his astonishing Architect’s Classroom Circa 1900 and everything in between, the common marvel is the microscopic detail.

Twin Manors (a lone one, as its counterpart is in a private collection) features authentic 18th century wood and brick. It also comes with some “secrets,” McKune said, such as a “tiny, tiny deed to the house” in the Newel post at the base of the stairs.

The Architect’s Classroom features stools that raise and lower, adjustable drafting tables and a wastebasket unfathomably made up of 1,020 solder joints.

The Art Deco Jewelry Shop, Marshall’s last commission, includes a chandelier composed of 15,800 beads and a man with a notable 5 o’clock shadow indicative of the evening scene.

There’s a “Dueling Pistols” miniature, with functional pistol mechanisms that the museum notes “have never been used in a miniature duel.” And the fully functional “Harpsichord,” which even comes with a tuning fork.

And, and, and …

We could go on.

We have gone on.

Chances are you will, too, if you do yourself the favor of a visit during the museum hours of 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. daily (except Tuesdays, when it’s closed).

As Cleaver put it for the Congressional Record in 2022, all the visitors over the years have “left a little younger” — and you can count me among those now.

Star sports columnist Vahe Gregorian is changing uniforms this spring and summer, acting as a tour guide of sorts to some well-known and hidden gems of Kansas City. Send your ideas to vgregorian@kcstar.com.