Doctors treating patients with persistent pain can use new strategies in treatment strategies.

Photo: APF/ Astier

New treatments for chronic pain offer hope for many doing it tough with “terrible” long-term disabling symptoms, including perhaps those with Long Covid or other syndromes, medical experts say.

A duo from the University of Otago – senior surgery lecturer John Douglas Dunbar and Associate Professor and GP Hamish Wilson told Sunday Morning’s Jim Mora that new understandings about what causes persistent pain from medical research points to new approaches for helping patients reduce chronic pain.

And there is reason also see potential spin off benefits for those living with long term fatigue, which is often associated with pain.

“We see how people are getting better with the modern neuroscience and how that’s been helpful for treating persistent pain or chronic pain. We think the neuroscience is quite good on this,” Wilson said.

“It’s saying that persistent pain and persistent fatigue syndromes are probably driven by similar mechanisms, and so if we apply what’s happening in persistent pain and the pain clinics there, maybe we can help people with persistent fatigue. So that’s where we’re being optimistic about this.”

Ignoring pain is not the answer: “it’s real”

Chronic pain occurs when the body does not get better from pain and it continues to affect people’s life over a long period, Wilson said. Examples include complex regional pain syndrome, fibromyalgia, chronic pelvic pain and persistent back pain.

As a GP he sees many patients with chronic pain and it can be “terrible” to live with, he said.

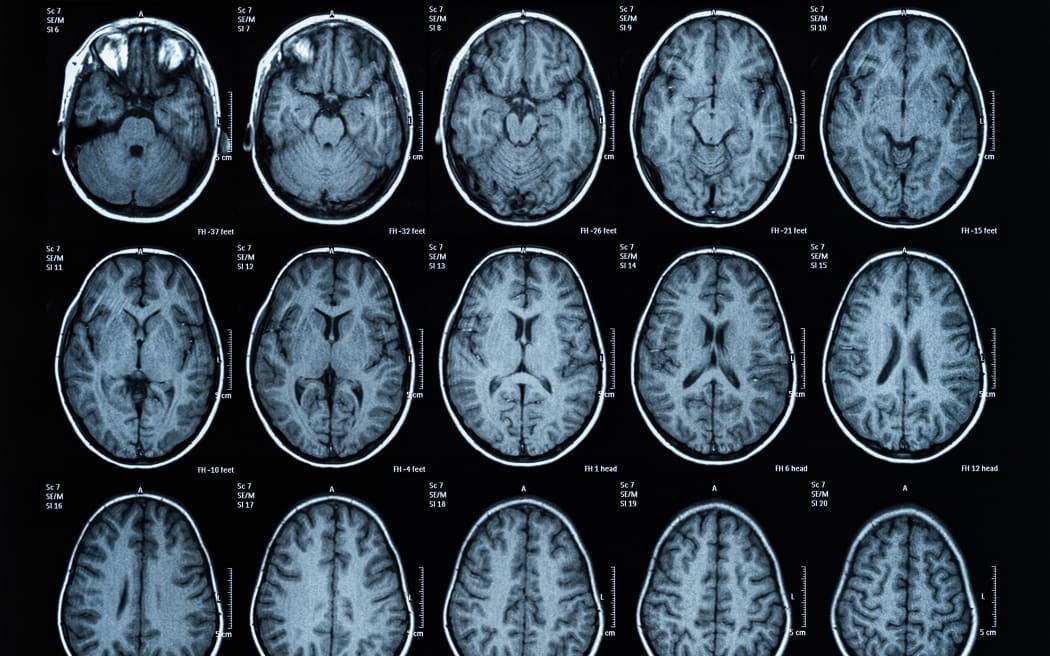

But there’s good news: “Suddenly in the last 20 years neuroscience has been just great because it’s really explained how people get these persistent symptoms – because you can’t see it on an X-Ray or a blood test or whatever.

“Neuroscience tells us that actually all sensation is created by the brain … generated by the central neurosystem, this is below our level of consciousness, we’re not in control of that.”

Dunbar said dismissing persistent pain and minimising its impact on the body is not helpful.

“It’s very important to realise that the pain is there, it’s real pain … the person is still disabled by pain,” he said.

“It’s not put on, it’s not imagined, it’s totally real, and you can’t ignore it. It”s not a simple matter of saying ‘there’s nothing there and moving on.”

The central nervous system is the origin of pain sensation – and offers ways to help address persistent pain.

Photo: Stefano Garau

There has been a movement away from using the outdated and unhelpful medical label ‘medically unexplained symptoms’, Wilson said: “The more recent, more accurate title is ‘persistent physical symptoms'”.

It is now thought that the brain mistakenly continues to interpret signals from the neural network into the sensation of pain and other messages to the body, long after it is helpful.

This process of “central sensitisation” in the central nervous system can include sending messages that cause inflammation, and result in fatigue to the body too.

“So the brain keeps producing these swelling and redness … and people have persistent pain and they can’t sleep and life becomes a misery,” Wilson said.

“The degree of pain or fatigue depends on lots and lots of factors.”

The new knowledge is being successfully used by persistent pain clinics, which have proved to be an effective approach to helping treat those experiencing it, he said.

How can the knowledge about central sensitisation help heal?

Understanding the wider contributing factors helps, Dunbar said. This includes searching for injury, tissue damage and physical contributing factors in the body.

“But if you can’t find tissue damage to explain the pain, or if you find that the pain is more than you might expect from that amount of tissue damage, then … what the research shows in the long term in chronic pain is that our thoughts, feelings and beliefs are more significant than the actual tissue damage.

“Pain becomes not a good indicator of tissue damage the longer it’s been existing. So we can start [working] on their thoughts, feelings and beliefs.

“If we can introduce new thoughts and behaviours to our consciousness … [they] will filter through and change the way our brain is processing the information at a subconscious level.”

Careful coaching by clinicians can help patients exercise and get moving by carefully ensuring they don’t exert too far to levels that flare their pain up.

Medications can be reviewed to ensure they’re still helpful for the stage the patient is at.

And ‘psychoeducation’ can help to identify beliefs, feelings and fears that could be unhelpful for their physical recovery.

How does the new approach to pain offer hope for diseases with fatigue symptoms like Long Covid?

The Hague: Patient advocates organisations presented a petition signed by more than 100,000 people calling for more research and support for those with Long Covid, including seriously ill and disabled patients, on 13 February, 2024.

Photo: AFP/ ANP

“The immune system and the central nervous system are all linked”, Dunbar said. “… If you get that [central nervous system] all fired up and over-protecting then the immune system goes wonky, and you don’t get better and you don’t sleep, you get tired and you get brain fog and all that sort of stuff.”

“What I’ve noticed is that in the research, people with persistent pain that go through that – their fatigue that was associated with the persistent pain also gets better.

“So you could say ‘actually the pain wasn’t necessarily the primary problem, the central sensitisation was the primary problem, and that causes both the pain and the fatigue.”

That means clinicians using the new approach to pain could consider whether it might be useful for their patients suffering from fatigue.

“So if we go back and try and treat the brain sensitisation and the brain inflammation, that’s the way to approach it, at the primary source,” Dunbar said.