Kevin Durant, Luka Doncic and Devin Booker each bring their unique style to the NBA, blending elegance, flair and modern trends to redefine athlete fashion. (Photo by Justin Casterline/Getty Images)

PHOENIX — As the Dallas Mavericks and Boston Celtics tip off Thursday in Game 1 of the NBA Finals, the primary focus will be on Kyrie Irving’s wizardry, Luka Doncic’s bionic eyes and Jayson Tatum’s exceptional wing play matched by Jaylen Brown’s extraterrestrial athleticism.

However, before stepping on the court, the superstars stroll through the arena tunnel. Here, one will witness the stylistic flair expressed in their outfit choices. For several decades, NBA players have taken pride in showing off their gameday clothing selection in the tunnel.

Still, whether it’s a vibrant suit, simple overalls, or a white T-shirt, the players’ freedom to express themselves through fashion derives from the American Basketball Association, an innovative basketball league that experienced its glory days from 1967 to 1976.

“When the ABA started, that was the first time that players could be themselves,” said former NBA player Jim Bostic. “A flamboyant style replaced a conservative look, and it became a fashion show.”

In 1977, Bostic, then a Detroit Piston, walked into a retail store to buy his first suit since entering the league two years prior. He purchased an Italian double-breasted suit in navy blue and pinstripes and patented leather black shoes that boasted a polished alligator pattern.

His choice illuminated a new era in NBA fashion that threw away a more traditional look of plain suits for a flashy style.

In April of the following year, Bostic played on an NBA court for the first time and encountered the same man who influenced his purchase and pioneered this new era: Philadelphia 76ers small forward and aerial master Julius “Dr. J” Erving. drive baseline and ascend.

Erving drove baseline and ascended for a dunk, but Bostic knew better than to contest Erving’s posterizing capability that dated back to their basketball runs at local New York parks when they were younger. Yet he did, and became a victim of his own ambition.

“I looked up to Dr. J on and off the court,” Bostic said. “His fashion choice inspired my decision in buying that suit because I saw his outfits and it made me step up my game.”

Erving’s fashion sense developed long before he joined the NBA upon joining the 76ers in 1976. It was revealed between 1971-1976, when he played in the ABA with the Virginia Squires and New York Nets.

The American Basketball Association

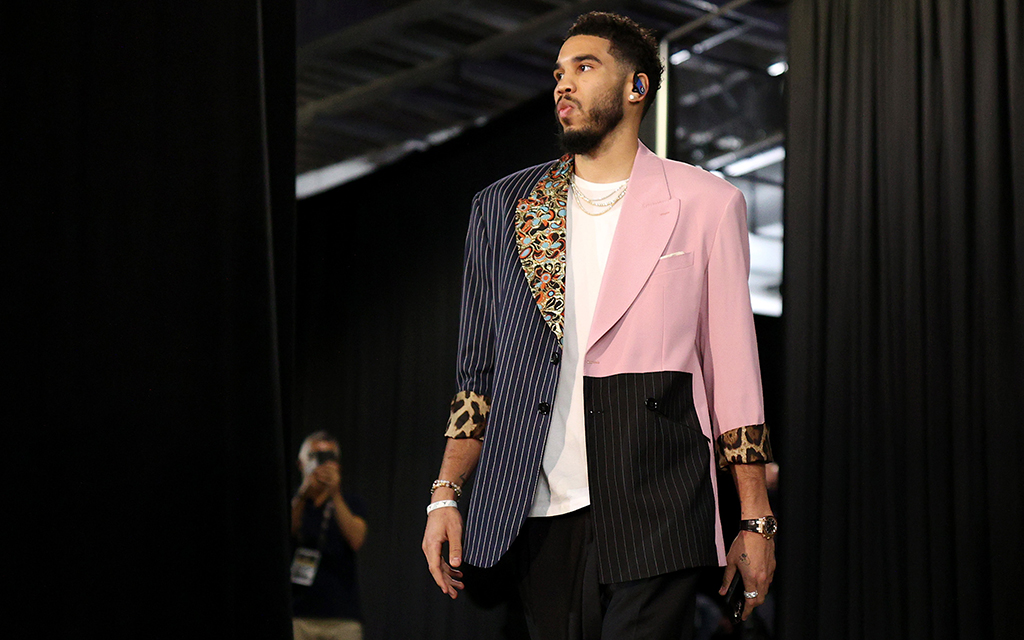

Jayson Tatum’s versatile fashion sense, ranging from classic suits to casual streetwear, mirrors his game on the court as an All-Star for the Boston Celtics. (Photo by Ezra Shaw/Getty Images)

The ABA prioritized a fast-paced game and made basketball a form of entertainment for the consumer. The league installed a three-point line and drafted players from high school, paving the way for three-point assassins such as Stephen Curry and straight-to-the-pros players like LeBron James.

The league also shifted All-Star festivities to the weekend and hosted the first Slam Dunk contest in 1976 in which Dr. J flew from the free throw line, clearing the runway for an epic dunk contest 40 years later between Zach Lavine and Aaron Gordon. Lavine and Gordon produced three straight 50-point dunks in the championship round from both participants.

These innovations accounted for stars who had the confidence to display crafty maneuvers on the court.

The players’ confidence and freedom in play had a direct relationship. It translated off the court with stylish, non-traditional outfits contrasting the usual plain suit worn by NBA players. This new trend reflected the avant-garde ABA spirit that inspires today’s NBA stars. During the ABA era, NBA superstars Wilt Chamberlain and Walt “Clyde” Frazier presented an idiosyncratic fashion atypical to the NBA as well. But, the NBA didn’t offer them idiosyncratic gameplay.

Mitchell S. Jackson, Pulitzer Prize winner and author of “Fly: The Big Book of Basketball Fashion,” appreciates the ABA’s ambition to boost player morale through original gameplay, which contributed to stylistic risk-taking.

“The ABA was trying to usurp the NBA as the go-to league,” Jackson said. “With all these freedom-based innovations to the game that distinguished them from the NBA, it’s hard for me to imagine a player who feels so free on the court to not have that freedom or feel that freedom in other aspects of their life, and fashion being one of them.”

Jackson, an English professor at Arizona State University, believes the license that players in the ABA held to express themselves on and off the court drives the mindset behind NBA players today.

“The freedom in the style in which the ABA was playing translated to some of the players and how they dressed,” Jackson said. “And I think that same ethos is true of today’s game. Confidence is so important for the players. Because why would you wear something to a game that made you feel less confident? So, the players need to wear things that make them feel strong and capable no matter their role on the team.”

Bold expression through bold empowerment

Allen Iverson redefined NBA fashion with his bold, hip-hop-inspired style, bringing authenticity and street culture to the forefront of the league. (Photo By Andy Cross/The Denver Post via Getty Images)

This emergence of player freedom in the ABA resulted from an arduous fight for civil rights for Black people.

The ABA launched three years after the Civil Rights Act of 1964. As the country challenged traditional barriers, the league exercised a keen awareness of the seismic shift and never considered limiting its athletes’ freedom through fashion.

Jackson believes the empowerment stemming from a civil rights movement that embodied boldness and defied the norms provided confidence to the Black athletes in the ABA.

Jackson likens the empowerment in the ABA to how the league felt after LeBron James broadcasted his decision in the summer of 2010 to join forces with Dwyane Wade and play for the Miami Heat.

“Players today have more power thanks to James’ South Beach decision,” Jackson said. “They have their own platforms now. They can be businesses that are as popular as a team. So, I think that that level of freedom and resources approximates to what the players in the ABA must have felt like when they first could do what they wanted to do, when they didn’t have to dress traditionally like the white dudes on the team, and when they were around on their own.”

Twenty-five years after the first three Black players joined the NBA in 1950, the four remaining ABA teams joined the NBA. By the mid-70s, the NBA was 75% Black.

“By the time we get to 1976, it’s a Black league,” Jackson said. “That fosters a level of empowerment when you look around and see yourself. That goes for today’s league, too.”

Bostic admits that a shared community at Rucker Park was present during the basketball runs between the budding stars who competed at the historic court.

Bostic believes that the style displayed in the ABA reflected internal desires they possessed from a young age but couldn’t afford to execute. As their crafty handles and flashy dunks were developed at Rucker, they pondered visions of artistic expression through fashion.

“The money they were making in the ABA was still a big deal for that time,” Bostic said. “When these cats went to the ABA, they already had a certain level of understanding of style and fashion. But the money that they were making allowed them to step up their game. It allowed them to buy shoes that cost several hundred dollars for the first time whereas before they may not have had the means.”

Bostic won two state championships as the boys basketball coach at Biondi High School in Yonkers, New York, from 1996-2002. Most of his players grew up in impoverished conditions.

By this time, the soul of NBA fashion rested in the soles of one man’s feet: Michael Jordan. However, during a time when everyone wanted to be “like Mike”, disadvantaged basketball players, like Bostic’s kids, didn’t have to attach their league aspirations to materials they couldn’t afford. They had someone else to look up to.

Two years before Allen Iverson crossed up Jordan during his rookie year in 1997, Virginia courts overturned a conviction deeming Iverson responsible for harm during a bowling alley altercation in 1993 in his hometown, Hampton, Virginia, eradicating a 15-year sentence.

Tapping into the bold expression ABA legends exhibited decades earlier, Iverson didn’t refrain from presenting himself authentically.

Only this time, it wasn’t flashy suits from boutiques that attested to financial prosperity. Instead, durags, large jewelry, and baggy fits reflected Iverson’s childhood experiences and endearment for hip-hop culture.

“My players tried to emulate him,” Bostic said. “They could afford to be like Iverson. They couldn’t afford Jordans. It brought them one step closer to the league mentally to know that someone like them had made it and is killing it.”

Akin to Erving and Gilmore, Iverson wasn’t alone in integrating a new style when the league and hip-hop intersected in the 1990s and early 2000s. Players like Carmelo Anthony, Stephen Jackson and Jermaine O’Neal, just to name a few, took liberty in embracing their roots through fashion.

To late NBA commissioner David Stern, Iverson’s fashion influence was detrimental to the league’s image. The “Malice at the Palace” on Nov. 19, 2004, in which a brawl between the Indiana Pacers and Detroit Pistons players and fans occurred, served as the crowning catalyst for Stern to restore the league to corporate America sufficiency.

The suits are back

Jaylen Brown’s fashion choices reflect his personality, merging high fashion with streetwear influences as an All-Star for the Boston Celtics. (Photo by Jim Davis/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

Stern implemented a dress code before the 2005-06 season, limiting players to wear only “business casual attire” and reintroducing a new generation absorbed with hip-hop culture to a league that Erving and Co. had to reimagine decades earlier. The mandate also prohibited headgear, T-shirts and chains, to name a few restrictions.

Former NBA All-Star and gold medalist Allan Houston played for the Knicks when Stern decided to enact a dress code. Although his peers initially resented the decision, Houston believes the players discovered something new about themselves.

“I think, due to the dress code, guys started to appreciate how good they looked,” Houston said. “They combined the corporate feel with their own fashion appeal.”

However, Houston, the founder of social impact and apparel brand, FISLL, acknowledged that what they learned was already discovered.

“When you think about it, that is what the 70s were,” Houston said. “There was style, but it had a corporate-fashion feel. When Stern established the dress code, we returned to understanding a mix between our cultural areas, elevated style, and a corporate look. The result was tighter suits.”

Stern’s plan backfired. In an attempt to restore order, he commenced a fashion revolution that led to fashion deals and sponsorships.

“Fast forward today, and the fashion scene in the NBA is about individual expression,” Houston said. “The players are very fashion-conscious, and it’s cool because there’s no one mold that we have to fit.”

Social media makes the NBA athlete a brand and grows the league

Today, the problems former NBA players dealt with is a thing of the past as the league has welcomed authenticity, player empowerment and all that comes with individual expression.

Wade’s sock affinity prompted a partnership with Stance in 2013. Russell Westbrook, the NBA’s all-time triple-double leader, published “Style Drivers” in 2017, documenting his audacious outfits and stylistic vision.

Today, Oklahoma City Thunder superstar Shai Gilgeous-Alexander is the new face of Kim Kardashian’s SKIMS men’s brand. SKIMS also recently became the NBAs new underwear partner.

As the NBA continues to make partnerships, a PricewaterhouseCoopers study reveals that the “global sports-sponsorship market is expected to grow from $63.1 billion in 2021 to $109.1 billion by 2030.”

“Athletes taking advantage of expressing themselves through fashion and the NBA doing these partnerships are an opportunity to capture the non-basketball fan and capitalize on money-making opportunities,” said Ta’Quan Zimmerman, a former NBA G League guard who is under contract as a FashionNova model. “When you enter the arena, you get people who know nothing about basketball that are watching.”

“Back in the day, people only saw the stars like Dr. J and Jordan off the court in commercials, only on television,” Zimmerman added. “Today, everyone is their own celebrity because of social media. So, you don’t need TV. You’re keeping engaged and pleasing your fans via social media.”

Zimmerman, who boasts over 100,000 Instagram followers, credits social media for this rise in attention.

“Now, we have segments like LeagueFits that show off the players’ outfits,” Zimmerman said. “Honestly, it’s cool to see what guys are willing to wear because it gives us a deeper insight into who they are. Look at some of the things Kyle Kuzma is wearing. Whether getting paid or not, he has the bravery to wear these outfits.”

Evolution is here, but ABA’s impact remains

Bostic admits to dressing in a more conservative look during his playing days. Today, though, Bostic rolls in his red Cadillac wearing a flashy suit akin to those of the 70s.

“Playing in that era influenced how I dress now for sure,” Bostic said.

Houston and Zimmerman also donned a traditional look during their playing days? While Zimmerman prioritized a “presentable” look with a button down and jeans as he tried to make it in the league, Houston remembers the fashion in the 70s and acknowledges his father’s attire guiding his fashion sense.

“I remember in the ABA they had the white collars and bell bottoms. There was a style factor,” Houston said. “I saw my dad wearing suits to games as a coach at (the University of Tennessee). I saw him wear the white collars in practice. So for me, I always like dressing up that way, and it passes on. My son had a bow tie when he was six because he wanted one. I didn’t make him wear it, but it’s what he saw.”

As for Jackson, his basketball curiosity made him learn enough about the sport that makes up for him never making the NBA. A part of that knowledge lends to a good sense of fashion.

He rocks polos as a professor, a black or gray fit that’s usually a bigger silhouette than as an author and “a lot” of jewelry as a way to personalize his outfit. His ability to adapt to the time is something he notices in Erving.

“I think he (Dr. J) had a style that kept evolving,” Jackson said. “I saw a picture of Dr. J a while ago wearing shorts, a windbreaker and a fitted cap. My man is like 70-something years old. But, to me, that’s evolution.”