Researchers from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have tested a new cellular immunotherapy whereby they engineered normal white blood cells (lymphocytes) from each patient to produce receptors that recognize and attack their specific cancer cells. Reported in Nature Medicine, the interim data in the phase II trial of people with metastatic colorectal cancer showed the personalized immunotherapy shrank tumors in several of the people enrolled and prevented tumors from regrowing for up to seven months.

While two other forms of cellular immunotherapy, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy and tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy, have proven to be successful treating some blood cancers and metastatic melanoma, respectively, developing cellular therapies to treat solid tumor has been challenging.

“The fact that we can take a growing metastatic solid cancer and get it to regress shows that the new cellular immunotherapy approach has promise,” said study co-leader Steven A. Rosenberg, MD, PhD, of NCI’s Center for Cancer Research (CCR). “However, it’s important to understand that these findings are preliminary and that the approach needs to be further refined and tested in more types of solid cancers.”

The new cellular immunotherapy appears to have solved a couple of the prior pitfalls that have hampered these therapies for solid tumors: how to create large numbers of T cells that recognize and only attack cancer cells and how to get the T cells to multiply once they have been reinfused to the patient.

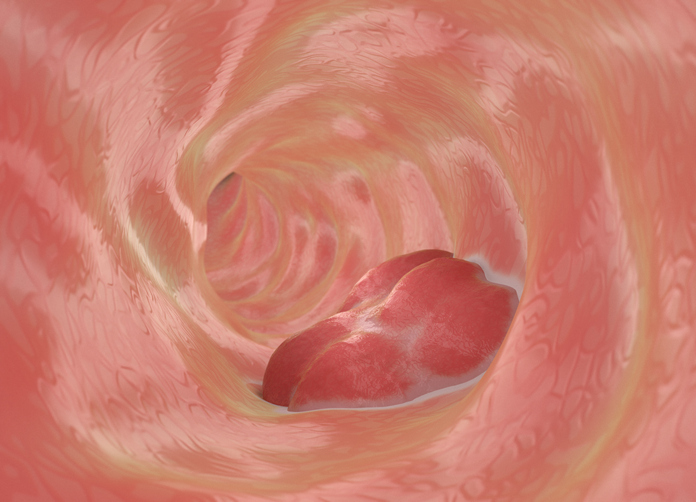

For this immunotherapy, the investigators collected lymphocytes that were present in each patient’s tumor, then used molecular characterization to identify and isolate T cell receptors on the lymphocytes (T-cell receptors) that recognized the specific changes in each patient’s tumor. After sequencing those receptors, the team used a retrovirus to insert the genes for the receptor into normal lymphocytes collected from the patient’s blood.

These genetically engineered lymphocytes were then grown in the lab to the hundreds of millions and then infused back into the patients.

“By taking the natural T-cell receptors that are present in a very small number of cells and putting them into normal lymphocytes for which we have enormous numbers—a million in every thimbleful of blood—we can generate as many cancer-fighting cells as we want,” Rosenberg said.

In the phase II trial, the team enrolled seven patients with metastatic colon cancer. All seven received doses of the immunotherapy pembrolizumab prior to receiving the cell therapy and a second drug called IL-2 afterward. Three of the patients showed large shrinkages of their metastatic tumors located in the liver, lung and lymph nodes, lasting between four and seven months. Median time to progression was 4.6 months.

The trial is ongoing and is treating patients with other kinds of solid tumors as well. Rosenberg noted that the team is working torefine the new therapy for future research.