The new document provides a much-needed update on the assessment, diagnosis and management of acute and chronic whiplash.

Provide education, use simple analgesics early and avoid imaging as part of the assessment – sound familiar?

The NSW State Insurance Regulatory Agency, in collaboration with the John Walsh Centre for Rehabilitation Research at the University of Sydney, published a draft of the new whiplash management guidelines last year and presented them for discussion during topical session at the Australian Pain Society annual scientific meeting in Darwin last month.

“The overall purpose of developing these guidelines is to improve health and social outcomes of people with acute and chronic whiplash-associated disorder by i) improving healthcare professionals’ understanding of the clinical features of WAD, ii) providing evidence based best practice recommendations for HCPs managing these people and iii) de-implementing non-recommended assessment methods and treatment modalities,” the draft document reads.

The guidelines recommend diagnosing the severity whiplash according to the Quebec Task Force Classification system and using either the Whip-Predict tool or the short form of the Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire to determine a patient’s likelihood of recovery or experiencing ongoing pain or disability – and whether they will require further assessment or treatment.

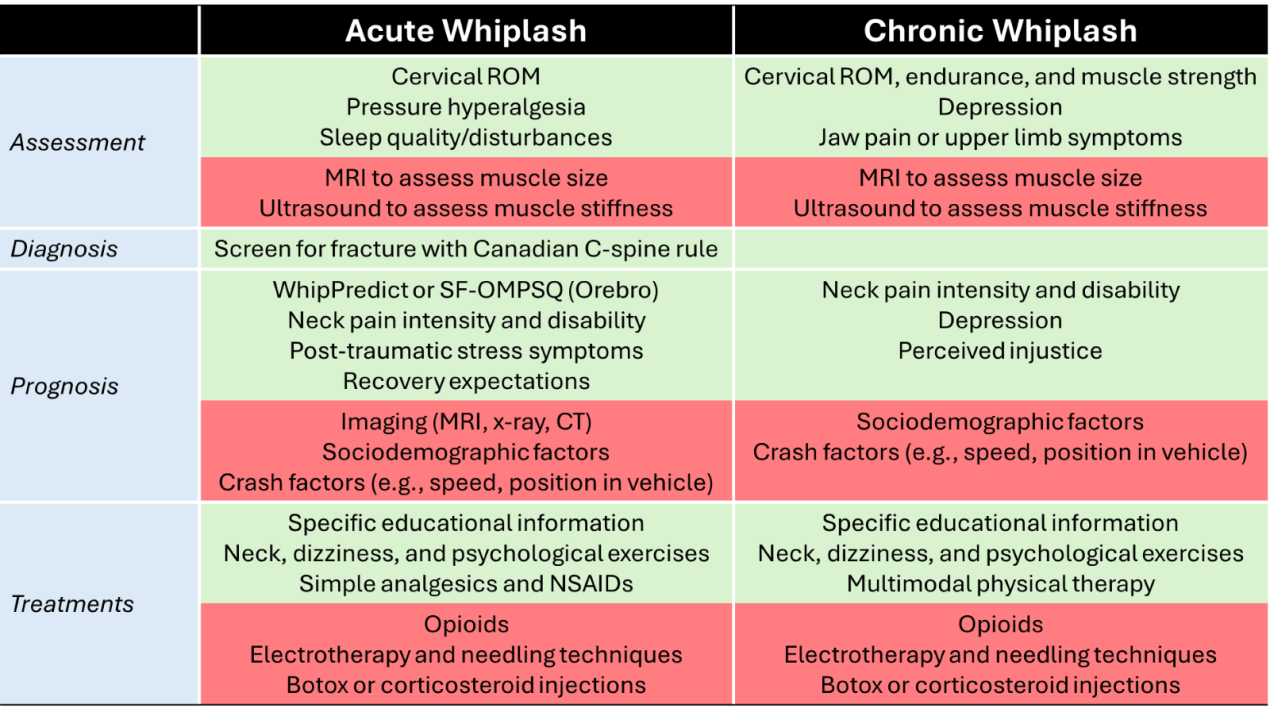

The recommendations suggest education along with psychological-, neck- and dizziness-specific exercise interventions and simple analgesics or NSAIDs were the most effective treatment for acute whiplash. There was less consensus regarding multimodal physical therapy, immobilisation and amitriptyline or pregabalin in the acute stage.

The new guidelines also contain an injury care flowchart, outlining the recommended assessments and treatment paths from the initial presentation of acute whiplash through to what to do if your patients are still experiencing chronic whiplash up to 12 months post-injury.

Psychological factors, such as depression or perceived injustice, and interventions, such as trauma-focused CBT, were conditionally recommended in the assessment and treatment of chronic whiplash.

Advanced imaging (i.e., MRI or ultrasound) to assess muscle size and stiffness were not recommended in the assessment of either acute or chronic whiplash, while there was a strong consensus against the use of opioids, electrophysiology and needling techniques and botox or corticosteroid injections as treatment.

Whiplash-associated disorders are a common injury following a non-catastrophic motor vehicle collision and cost Australia over $950 million each year. About 50% of people with a whiplash injury don’t recover within 12 months.

The guidelines for managing acute whiplash were last updated in 2014, while the chronic whiplash guidelines were last updated in 2008. The RACGP will be approached to formally endorse the new guidelines when they are finalised.

Patients and healthcare professionals are encouraged to use My Whiplash Navigator, a self-directed program designed to help assessment and recovery following a whiplash injury. The program contains six free modules whose content reflects information included in the updated guidelines.