Prevention of common pregnancy complications has the potential to improve maternal health, reduce long term metabolic and cardiovascular risk, decrease transgenerational transmission of future disease risk to babies, and reduce hospital costs.

Women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) have an increased risk of pregnancy complications including miscarriage (odds ratio, OR 1.5, gestational diabetes (OR 2.35), preterm labour (OR 1.54), and pre-eclampsia (PE) (OR 2.28) (here). Women with a history of pregnancy complications have a significantly increased risk of long term premature mortality. Despite these risks, women with PCOS are not included in risk assessment algorithms and have a lack of adequate counselling about pregnancy complications.

Our recent review has focused on the risk of PE in women with PCOS, but many of the concerns identified and discussed relate to all women considering pregnancy.

PCOS is a multisystem metabolic and hormonal disorder that affects 8–13% of women, can be associated with disabling symptoms, is the most common cause of infertility, can be a progressive metabolic condition, and results in reduced quality of life.

PE affects 2–7% of pregnancies globally and is responsible for 70 000 maternal deaths and 500 000 fetal/neonatal deaths every year.

In Australia, PE occurs in 1–5% of pregnancies and varies by ethnicity (here). Severe PE occurs in 1–2% of pregnancies and complications associated with this condition account for 15% of direct maternal deaths and 10% of perinatal deaths. PE is the indication for 20% of labour inductions and 15% of caesarean deliveries and accounts for 5–10% of preterm deliveries. As a result, PE results in significant health care costs. In addition, the experience of PE can be traumatic to women, their partners, and their support networks (here).

Lifestyle factors have long been suspected in increasing the risk of pregnancy complications. The previous emphasis on smoking, alcohol, diet and exercise has expanded to include stress, sleep, community engagement, social supports, environmental chemicals, and the effects of climate (here). International and national guidelines recommend lifestyle interventions, such as diet and exercise, for the management of women with PE and PCOS. The challenge facing the health care system is to promote awareness of the recommendations and develop effective strategies to encourage rapid implementation in clinical practice.

Significant advances in PE research over the past 20 years have resulted in the development of effective screening tests that can help identify women at risk of developing PE in early pregnancy (multivariate screening) and throughout gestation (angiogenic ratio testing). Women identified as high risk on screening can be offered treatment with low dose aspirin, which has been shown to reduce the incidence of preterm PE by 62%. The recommendations for screening and treatment of high risk women apply to all pregnant women.

The model in practice

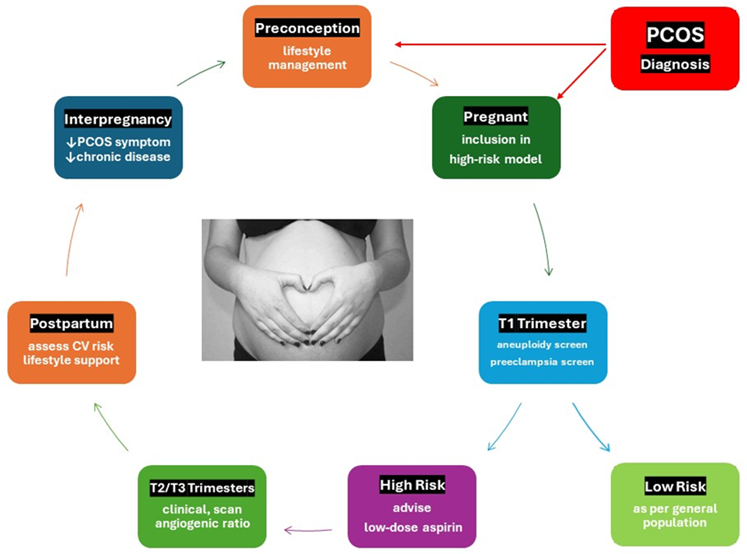

As a result of our research, we have proposed a screening and management model for women with PCOS, before, during and after pregnancy (see Figure 1 below). PCOS is one of 78 risk factors for the development of PE in pregnancy. A hierarchical review of the evidence (by an expert international advisory group) reported that obesity (body mass index > 30) was the top risk factor based on high level evidence. Many of the risk factors have a lifestyle component and lifestyle interventions outlined in the Australian Government’s National Preventive Health Strategy 2021-2030 equally apply to women considering pregnancy.

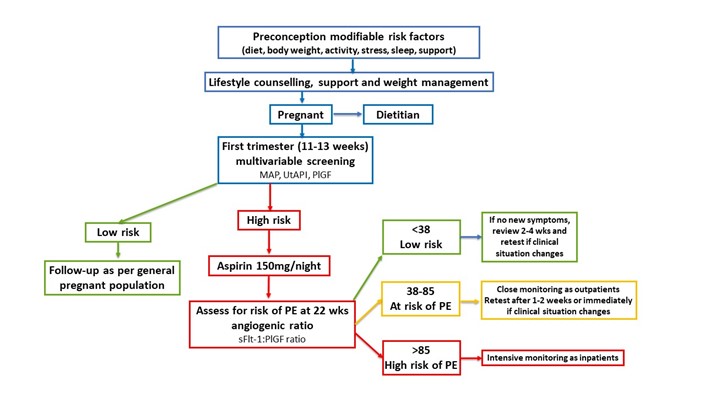

Once pregnant, both the international and Australian guidelines recommend that all women have multivariable screening for PE at 11–14 weeks gestation, at the same time as screening for genetic conditions. Approximately 10% of women will be identified as high risk and can be offered the option of preventive treatment with daily low dose aspirin until 36 weeks gestation. We have recommended that high risk women have ongoing assessment with blood tests that assess the angiogenic ratio, which measures the ratio of placental biomarkers sFlT-1 to PlGF, where available. These measurements can begin at 22 weeks and are used in conjunction with ultrasound scans, blood tests, fetal monitoring, and clinical assessment, to identify and manage pregnant women prior to the onset of serious complications associated with PE (see Figure 2 below).

Internationally, components of this model have been shown to be associated with a significant reduction in PE-related pregnancy and neonatal complications, and health care costs. In Australia, the introduction of early pregnancy PE screening has been estimated to result in a significant decrease in health care costs. We expect that the combined benefits of our recommended model will be even greater. Clinical evaluation is currently under investigation in real-world implementation studies.

Current challenges in the implementation of this model

Preventive lifestyle-specific guidelines should be developed for health practitioners involved in pre-pregnancy care of women considering pregnancy. Education campaigns should be developed to inform health care practitioners involved in antenatal care about the importance and practical implementation of the new screening tests.

Protocols for the measurement of mean arterial blood pressure need to be implemented. Ultrasonographers will need to be upskilled and accredited in techniques for assessing uterine artery pulsatility index, which is a measurement taken at the time of the first trimester ultrasound. Protocols to ensure that laboratories comply with quality control of serum biomarker assays will also be needed. Doctors managing pregnant women will require information about how to integrate angiogenic ratio results into existing clinical management practices.

Looking ahead

The importance of lifestyle interventions for reducing the risk of pregnancy complications needs to be emphasised in public health campaigns and antenatal education. All lifestyle-related public health messages associated with the implementation of the National Preventive Health Strategy should include reference to prevention of pregnancy complications and future health problems in mothers and babies.

Effective implementation of the recommended model has the potential to reduce pregnancy complications, decrease social disruption, hospitalisation, and time away from work and family, save health care costs, and remove some of the burden of care from a resource-stretched hospital system.

The implementation of this model has some limitations. Equity of access to qualified professionals will take time during the training and implementation phase. The multivariable model has a 10% false-positive result rate, so some low risk women will be assessed as high risk. Adequate counselling will be required, and refinement of the algorithm is ongoing. It will take some time for antenatal carers to develop experience integrating angiogenic ratio results into clinical management.

Conclusion

Individual components of the model have already been successfully implemented in many tertiary hospitals around the world. Our proposed model integrates the existing screening tools with lifestyle and medical management strategies. We believe there is a strong evidence base and demonstrated cost advantage to support the introduction of this model within existing Australian health care settings. Successful implementation could be fast-tracked through accredited National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Research Translation Centres and requires appropriate resource allocation from both governments and health service providers.

Jim Parker is an honorary clinical associate professor in the School of Medicine at the University of Wollongong and a former obstetrician, gynaecologist, and endoscopic surgeon.

Claire O’Brien is an associate professor in virology at the University of Canberra.

Christabelle Yeoh is a medical practitioner, Next Practice Genbiome, Sydney.

Felice Gersh is an obstetrician and gynaecologist and medical director of the Integrative MGI in California USA.

Shaun Brennecke is the University of Melbourne Dunbar Hooper professor of obstetrics and gynaecology at the Royal Women’s Hospital in Melbourne.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.