Around the country, private maternity hospitals are closing, with enormous implications for many Australians needing care and for the health system as a whole.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had profound effects on Australia’s health system, not least of which has been the enduring pressure on our public hospitals. More Australians are waiting longer for planned surgery than ever before, emergency department congestion is at record levels, and ambulance ramping is costing lives. At the same time, access problems for older patients seeking aged care mean that public hospital beds are often filled with people who do not need acute care but have no place to go outside of hospitals. Ways of trying to keep people out of hospitals — accessible and affordable general practice to manage acute and chronic health problems, and expensive urgent care centres — are struggling to keep up with demand for services.

In the current environment, it might be expected that Australia’s private hospital sector is thriving as people seek alternatives to our public hospitals. Certainly the numbers of Australians taking out private health insurance is increasing, reversing a trend of decline over the years before the pandemic. However, despite promising signs that private health insurance is enjoying a renaissance, all is not as it seems. There are concerning signs that Australia’s private hospitals are struggling to remain viable after serving our health system for decades. At a time when our public hospitals are struggling to cope, failures in the private hospital sector would strike a major blow for many Australians needing care and destabilise the entire health system.

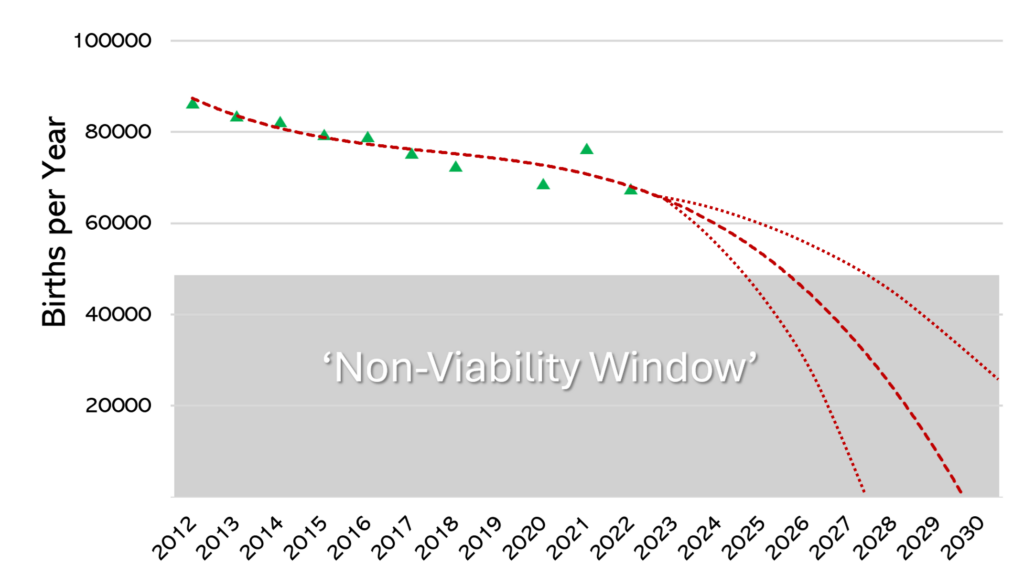

An area of great concern, and likely the harbinger, is that of maternity care. Thirty years ago, almost 40% of all births occurred in private hospitals in Australia. If women who use their private health insurance in public hospitals are excluded, it is likely that in 2024 less than 20% of births will occur in private maternity hospitals based on trends after the pandemic. In the decade from 2012 to 2023, the number of babies born in private hospitals fell by 22%. Taking into account these trends as well as falling birth rates and other societal factors, our preliminary modelling is predicting that the number of births occurring in Australian private maternity hospitals are likely to fall precipitously. So quickly that, by the end of the decade, private maternity hospitals will cease to exist (Figure 1). Such a loss of capacity has enormous implications for the health system as a whole, which we would like to explore here.

The first factor underpinning our prediction is demographics. Australians are having fewer babies with our birth rates — like those in all high-income countries — showing no sign of stabilising. The rates of decline in childbearing are steepest for women and couples in higher socio-economic groups. This is important because socio-economic status influences a person’s capacity to afford private health insurance premiums. As things stand, full reproductive health cover — including pregnancy and birth cover — is included only in gold insurance policies. Many women who do hold private health insurance still choose to birth in public hospitals. This is related partly to the attractiveness of models of care offered by many public hospitals, and also with the disincentive of out-of-pocket costs that accrue even with top-level health insurance.

A recent National Association of Specialist Obstetricians and Gynaecologists analysis of data provided by the Department of Social Services for 2022 revealed that, of women who began antenatal care with a private obstetrician, 40% did not continue. Another factor is age, with young women — the group most likely to use maternity services — having lower rates of private health insurance cover. Statistics from the start of 2024 reveal that only 5% of all private health insurance payouts were for maternity care. Yet data reveal that women value continuity models with private obstetric care rating highly, and roughly half of births in Australia will require either instrumental assistance or caesarean section, so non-obstetrician group practice models cannot deliver true continuity for many women who would value it.

Around the country, private maternity hospitals are closing. This trend is occurring in Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and Victoria. The causes of these closures are multiple but one of the key issues is staff shortages. Maternity care is labour-intensive — pardon the pun — and finding skilled staff is proving a major challenge for private hospitals. The available midwifery workforce has been falling and training new midwives takes time and resources. Providing attractive pay and conditions is difficult in private hospitals, meaning that public hospitals are becoming more competitive and attractive to staff.

Midwives are not the only group critical to providing care in private hospitals. Anaesthetists and paediatricians are essential and must be available around the clock. Difficulties in securing enough of these specialists to work in private hospital maternity rosters is recognised as one of the drivers of private maternity hospital closures. Similarly, providing care to private patients requires 24-hour commitment from obstetricians. As older obstetricians who commonly worked in solo private practice retire, a move to obstetric group practice is taking place. However, no obstetric practice can be offered if a staffed maternity hospital — with midwives, paediatricians, anaesthetists and others —isn’t available.

Private health insurance in Australia is community rated, which means that any Australian, no matter their state of health or need for care, pays the same premium with the same insurer except, as previously explained, for women wanting reproductive health cover. For this reason, making sure that a large pool of healthy people are committed to paying premiums is critical for the sustainability of the system as a whole. Among the key drivers of healthy young Australians taking up private health insurance with hospital cover are maternity and mental health care. In a cost-of-living crisis the value proposition needs to be very clear to healthy young people not only for taking out, but maintaining over a lifetime, private health insurance.

At the moment, with demographic and other forces coalescing, our modelling suggests that the viability window for private hospitals to provide the resources necessary to run maternity services (the supply side) will not be sustained by demand for much longer. With the closure of private mental health beds also playing out at the same time, the value proposition for healthy young Australians to pay for health insurance seems likely to dwindle. With fewer private maternity facilities available, especially in regional areas, even women who hold health insurance have nowhere to use it. As things stand, our prediction is of the private maternity sector rapidly running out of steam – and that is bad news across the board.

Caroline de Costa was formerly a professor of obstetrics and gynaecology at James Cook University College of Medicine and Dentistry, Cairns, and is now a researcher at The Cairns Institute, JCU .

Gino Pecoraro (OAM) is a Brisbane-based obstetrician and gynaecologist at the University of Queensland. He is the current president of the National Association of Specialist Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, former board chair of the Australian Medical Association and a past president of the Queensland branch of the AMA. A/Prof Pecoraro does work in private obstetrics.

Steve Robson is an obstetrician, gynaecologist and health economist. He is president of the AMA.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.