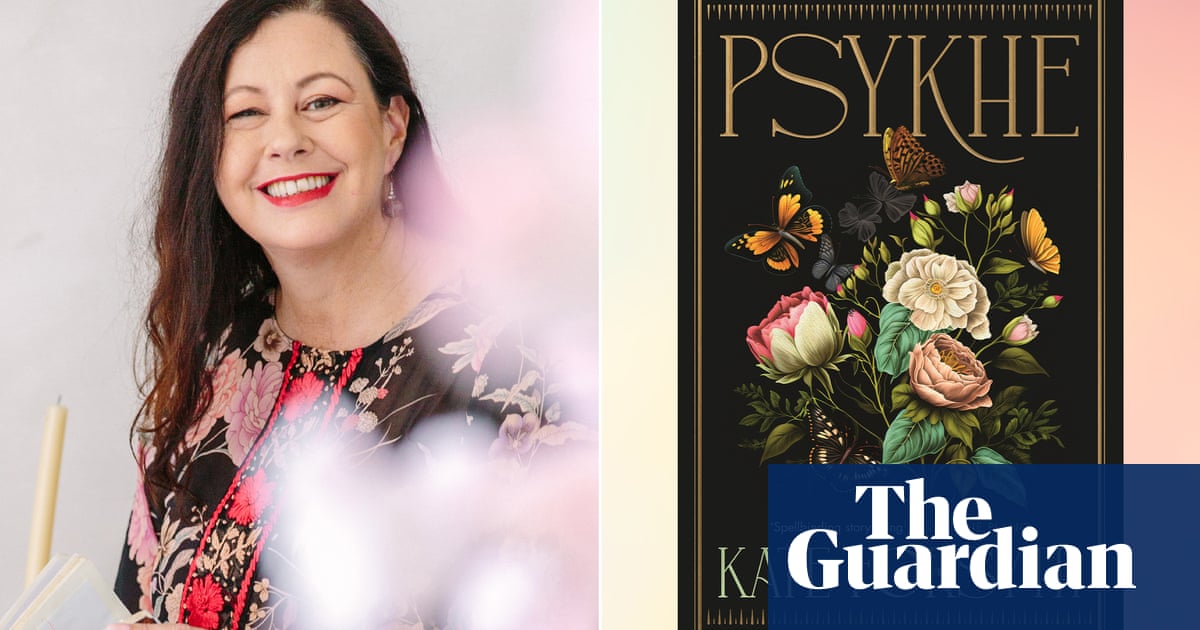

An award-winning novelist, poet and researcher with a doctorate in fairytale studies, Kate Forsyth is known for her female-led novels that bring together familiar threads of myth and magic with the predictable comforts of romance and history. In Psykhe, she takes on the Greek myth of Eros and Psyche, which she credits as being the “taproot” for one of her favourite stories, Beauty and the Beast.

In Greek mythology, Psyche, the most beautiful of three human sisters, falls in love with a god, Eros, the son of Aphrodite and the embodiment of love itself. But, as is the way in all good mythology, Eros comes with strings attached: Psyche is forbidden to see him. If she does, the story goes, he’ll disappear for ever. But Psyche’s sisters, envious of her happiness, plant seeds of doubt until, in the middle of the night, Psyche tries to catch a glimpse of her husband by the light of an oil lantern, which drips on him and wakes him up. As promised, he flees. Unlike many myths though, Eros and Psyche are given a happy ending, earning the favour of the gods and living happily ever after in the sky.

Forsyth’s Psykhe is far less passive. At first she is meek, the oddest of the three sisters and responsible for getting their family cast out of favour after she saves a bird marked for sacrifice. Her father blames her for angering the gods and her sisters seem caught between envy and disdain. But in the remote, gloomy watchtower where Psykhe is cast out with her sisters, she begins to thrive.

Nocturna, the old midwife who acts as the tower’s gatekeeper, takes Psykhe under her wing, teaching her herbalism and healing. Stripped of creature comforts and royal society, Psykhe’s sisters suffer and complain but, free from her father’s watchful eye, Psykhe blossoms. When she meets Ambrose, whose black curls and hazel eyes cause “an odd twist in the pit of [her] stomach”, she comes to life with desire.

Forsyth attributes her fascination with the Psyche myth to its celebration of “female desire and disobedience, and [the way that] its denouement leads to love and liberation, not sorrow and suffering”.

But Forsyth’s Psykhe does suffer. Some of the trials that she and other women in the book are forced to endure at the hands of gods and men are described in cruel detail – in particular the myriad ways in which women are carelessly made the playthings of both. And, like the original tale, when she confronts Eros/Ambrose’s mother, Venus (the Roman name for Aphrodite), Psykhe is set three impossible tasks that see her stripped of everything she once held dear.

But Psykhe is also more liberated than her mythological inspiration. She is given more than love; she has agency, knowledge, intellect, respect. Other characters, including her sisters – who are written with far more nuance here than in the original myth – care for her. She is more than her beauty, more than an object of desire. Forsyth raises the relationships between women, in particular the calm that Psykhe finds in her friendships with older women, to the level typically reserved for romance. Ambrose, ultimately, is still the prize but Psykhe is able to write her own tale.

In some ways though, the things that make Psykhe so comforting also strip it of its teeth. The novel is predictable, familiar; her gutsy resilience; the ability for love overcoming all obstacles – all are a balm on a cold winter night but it also feels naive and simple. While it’s always a win to see a woman unashamed of her desire, and women looking out for one another, Psykhe is nice at the cost of being interesting. She cares for the injured, comes back to her father – no matter how badly he treats her – and will consider the needs of an ant before her own. Compared with Madeline Miller’s Circe, a much pricklier female character, Psykhe feels somewhat unsatisfying.

after newsletter promotion

Ultimately, the novel succeeds in its ambition to entice and delight. Forsyth is an assured writer who knows her stuff when it comes to myth, a storyteller who can draw the reader in with quiet confidence. The outsider coming to power; the thrill of a magical assist; the familiar rhythm of being taken on a journey that leads you there and back again – it’s an alluring opportunity to leave behind the worries of reality for a while. But you may find simple comfort isn’t enough.