If you feel like your six-year-old has suddenly gotten extra fussy about the texture of their dinner, don’t worry. It will pass. A new study from the University of Copenhagen’s Department of Food Science demonstrates that at the age of six, children prefer to avoid crunch in their peanut butter, berries in jam and pieces of fruit in yogurt,

In the study, the researchers asked 485 children between the ages of five and twelve to choose between six different foods with and without lumps, seeds and pieces of fruit in them. The foods were bread, orange juice, peanut butter, strawberry jam, yogurt and tomato soup. The researchers showed children drawings of these foods both with and without lumps, and then asked them to choose between them.

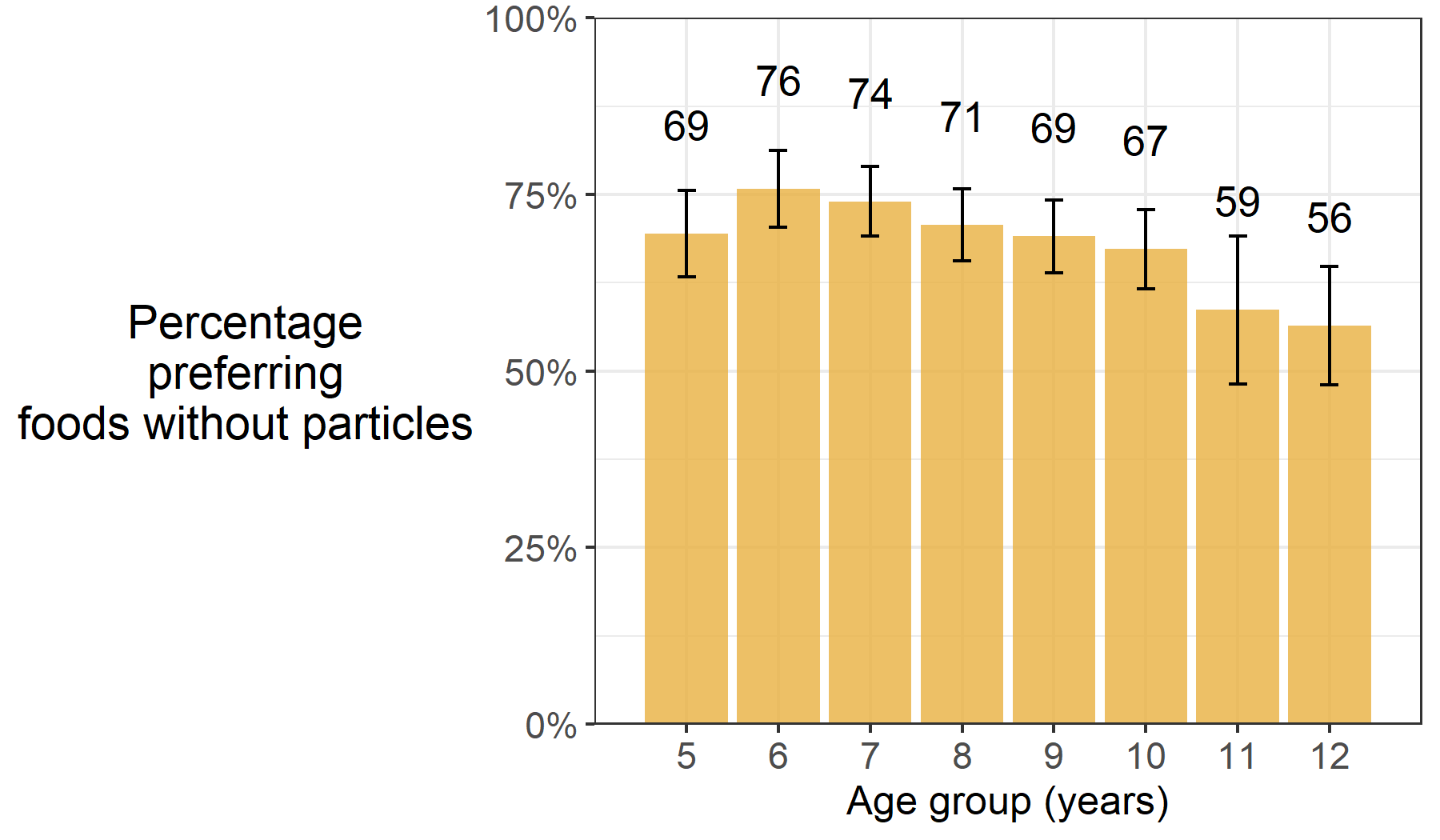

In 76 percent of the instances, six-year-olds opted for foods without lumps, the highest preference rate observed across the age groups.

“The fact that children in general are not happy with too many lumps in food is probably something many people can recognize, but this is the first time that a scientific study has linked a specific age group, namely six-year-olds, so clearly to this food preference,” says Dr. Ching Yue Chow, first author of the study.

To get answers that were as precise as possible, the researchers have used real foods to test how consistent children were in answering these questions in other studies.

Protection against dangerous foods

According to Ching Yue Chow, there may be an explanation for why children’s fear of complex texture in food peaks around the age of six.

“Food neophobia is often described as the reluctance to eat new or unfamiliar foods. It is thought to be a protective function to prevent children from eating potentially poisonous foods or other dangerous things when they start to become more independent. Studies have reported that food neophobia starts from a low baseline at weaning. It increases sharply as a child becomes more mobile and independent, reaching a peak at around 6 or 7 years old.

As such, it makes sense that this particular group in our study does not like too many lumps in food, as it is at this age that they are most cautious when it comes to food,” explains Ching Yue Chow.

The researchers also examined whether chunk size in food has anything to say. But here, they found no unequivocal answer.

“It seemed that the children generally had no problem in distinguishing different sizes of chunks when foods were in their mouths. For them, it’s mostly about the presence or absence of chunks,” says Ching Yue Chow.

However, despite there being a low point in the desire to eat food with chunks at the age of six, it gradually goes the other way in 7-12-year-olds, the study shows. And this is supported by our previous knowledge in advance of how children’s food preferences mature with age.

“As children reach school age, they may become more influenced by classmates and others within their circle to try new types of food and have more of a desire to expand their horizons. We can also see that the proportion that would like to have food with chunks in food grows in concert with their age in the study,” says Ching Yue Chow.

New dishes may need to be introduced 8-15 times

And according to the researcher, the “anti-chunk phase” that 6-year-olds have, you have to accept as a parent, although it can be frustrating when the kids don’t want to eat the food they’re served. But that can easily change once they’re past the critical age of six. You just have to keep trying – often up to 15 times, the recommendation goes:

“A lot of research on children and foods shows that repeated exposures to new dishes have a positive effect on whether they’ll bother eating them. Specifically, it is about giving children the opportunity to taste new food while there is something on the plate that they already know. Often they need to be presented with the new dish 8-15 times before they develop preference for it, but persistence pays off,” explains Ching Yue Chow.

Furthermore, it’ a good idea to avoid compulsions and rewards for children to eat their vegetables.

“Rewarding a child with an ice cream if they eat their broccoli, is a very short-term strategy. Because the moment you remove the ice cream, they don’t want to eat the healthy foods. At the same time, you shouldn’t pressure a child or try to force them to eat certain things, because you risk that they will eat the new food even less than before because they associate it with something negative,” says Ching Yue Chow.

The new research results shed more light on the food preferences of children between the ages of five and twelve, which the researcher hopes can make parents and the food industry wiser about our relationships with food.

“It is important to understand the underlying psychology of children when you, as a parent, serve them food and when you as a company develop new products to avoid children becoming unnecessarily picky. Here, I hope that our study can serve as an inspiration to parents and those who develop new food products,” concludes Ching Yue Chow.

About the study

- The research was carried out in a close collaboration between Future Consumer Lab, Department of Food Science, University of Copenhagen and the CASS Food Research Centre at Deakin University, Australia.

- The researchers behind the study are: Ching Yue Chow, Anne C. Bech, Annemarie Olsen, Russell Keast, Catherine G. Russell and Wender L.P. Bredie.

- The study involved 485 Australian children aged 5-12 years.

- The study is funded by Innovation Fund Denmark and Arla Foods.