This project originated from the observation that while many communities (particularly low-income communities and communities of color) want to lead data collection efforts that enable them to create and implement their own policy and programmatic agendas, traditional research designs and ecosystems do not generally enable this type of community leadership and engagement. Traditional research models in which communities are the subject of the research typically empower researchers and funders, because both types of entities control important levers of the research ecosystem. This includes the development of research questions, control of the research budget, latitude and incentives to publish without acknowledging community members as co-creators, and determining the locus of the funding.

As a result of these realities, we designed our project to answer the following question: What are the conditions under which communities can be in greater control of research and data governance more generally so that they can advance their own public policy or programmatic agendas?

Community data justice model proposal

To answer this research question, we conducted an extensive literature review, identified and reviewed extant models of community-based participatory research, conducted stakeholder interviews, and convened roundtables of community organizations, researchers, government, and media participants. As a result of this process, we were able to conclude that existing research and data governance models can be transformed if funders, researchers, and community partners embrace important changes in research infrastructure that include adopting collaborative research behaviors and planning research projects with communities. This will lead to enhanced sustainable research capacity, the creation of impact-focused solutions, and contributions to on-going research-community partnerships.

If the above changes are adopted, supported, and encouraged, the resulting shift in the power balance between communities, researchers, and funders should allow communities to:

- Conduct their own research with or without research partners

- Shape the narrative that emerges from research and analyses

- Pilot community-generated initiatives to enhance or address particular outcomes

- Sustain community research capacity and initiatives that emerge from research and analyses over the long term

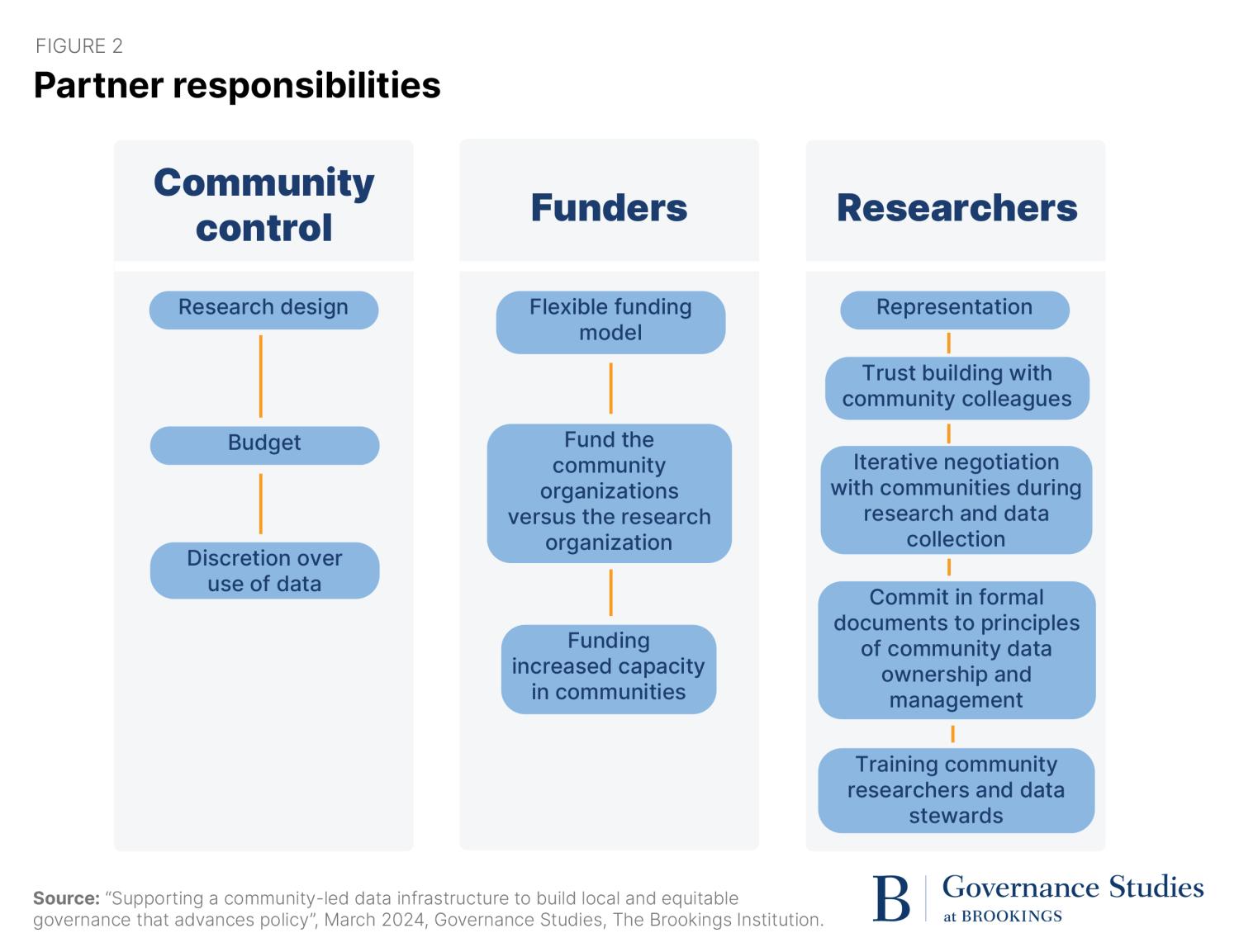

To support this model, we recommend that researchers:

- Spend time and effort building trust with community partners

- Engage communities in iterative negotiation at the onset of projects and along the way through research design, implementation, and analysis

- Formalize all of the outcomes of these negotiations with memorandums of understanding (MOUs) spelling out data ownership and management within the partnership

- Train community researchers and data stewards

- Represent the diverse backgrounds of the communities with whom they are partnering

We also recommend that funders support this model by:

- Providing more time for researchers to work within funded projects to allow for community engaged research approaches that are time intensive

- Increasing flexibility in the funding process to allow for the other principles we outline to come to fruition

- Placing funding opportunities within community organizations and not in research institutions

- Building capacity of community organizations through direct funding whenever possible

Community partners should also have opportunities to negotiate their control over research and data governance. We recommend that they prioritize the following actions:

- Negotiate the research agenda, design, and implementation

- Negotiate authority over the collection and use of community-based data

- Be prepared to connect with and communicate with journalists and the media broadly

- Negotiate research budgetary control

- Request funding to build and sustain in-house research capacity

Piloting and refining the community data justice model

Throughout the project, we had the opportunity to identify several promising case studies that showcase organizations and approaches that improve community control over research and data governance. While these case studies were encouraging, they did not include all of the elements we articulate above in our model. Additionally, consultations with the many stakeholders involved in the project allowed us to determine that there is an opportunity to pilot promising practices across a range of research partnerships. To that end, we aim to develop and test a set of tools that enable researchers and community members to implement the important behaviors and approaches recommended to realize our community data justice model.

This project originated from the observation that while many communities (particularly low-income communities and communities of color) want to lead data collection efforts that enable them to create and implement their own policy and programmatic agendas, traditional research designs and ecosystems do not generally enable this type of community leadership and engagement. Traditional research models in which communities are the subject of the research typically empower researchers and funders because both types of entities control important levers of the research ecosystem. This includes the development of research questions, control of the research budget, latitude and incentives to publish without acknowledging community members as co-creators and determining the locus of the funding.

As a result, while research and data collection undertaken in the context of this model has generated important insights for generations, the model itself does not promote equity among communities, researchers, and funders in the research and data governance ecosystem. Community-oriented research in which communities do not control the collection and use of data often feels very extractive, repetitive, and devoid of impactful solutions that advance the goals of community members. When communities do not have control over the research agenda, design, and data governance, their agency is limited, which may perpetuate biases and inequity. Because data has the power to define narratives, it is important that historically disenfranchised communities have the power to ensure equitable data interpretation, representation, and accountability.

While we acknowledge the rich research tradition of community-based participatory research methods and a number of innovative community-oriented funding models, we found that there are limitations, even when these approaches are practiced with care and intentionality. For example, there are limitations to the amount of latitude and discretion communities themselves can exert in determining study design, narrative control, and data governance more generally because they control neither the resources used to fund the research, nor the methods for data collection and use of data to determine outcomes.

As a result of these realities, we designed our project to answer the following question: What are the conditions under which communities can be in greater control of research and data governance so that they can advance their own public policy or programmatic agendas?

This project was designed to understand the extant literature and existing practices of community –engaged research, the infrastructure needed to enhance community-academic partnerships, and to discover better ways to generate evidence to support community action.

To carry out our work plan we devised a multi-stage process that allowed us to learn from researchers, practitioners, journalists, and leaders across academic disciplines and fields of study by employing a mixed-methods approach to examine our research questions. Our research design includes:

Stage 1: Discovery process

- Conducting an extensive literature review that included journal articles, book chapters, and public reports

- Identifying and reviewing extant models of community-based participatory research

Our landscape analysis sharpened the questions we utilized to guide our qualitative data collection and directed us to the range of individuals included in our interviews. Our team utilized the following process to identify relevant literature and conceptual models to inform our summary of the overall landscape.

Drawing on terms from the literature, such as “community-based” and “community-centered,” helped to narrow down the appropriate content to base our initial research focus. From there, we were able to discern which types of organizations were employing useful models that prescribed to developing partnerships within the research process. Health organizations showed promising results in this regard, and we found many useful examples of community-centered work from the Center for Disease Control (CDC), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the American Public Health Association (APHA).

Stage 2: Scholar and practitioner listening and learning process

- We identified case studies and organizations where communities have control over data governance and/or research questions and design. Similar to the landscape analysis, these case studies were largely based on existing research and on our team’s extensive knowledge of community-based research to guide our search for the most relevant organizations to examine. The case studies were supplemented by interviews with researchers from each case study’s organization. That effort uncovered interesting community-based research approaches such as those of the Ferguson Commission, the Native Lands Advocacy Project, the Greensboro Health Disparities Collaborative, the Abriendo Puertas research approach, and the University of Virginia’s CLD3 model. The latter four models are profiled in our case studies section.

- Overall, we spoke with 34 stakeholders, 17 of which were in individual interviews and 19 throughout our three roundtable discussions (two roundtable participants were individually interviewed before). We then recorded interviews with eight select individuals who participated in the roundtables.

- We conducted semi-structured preliminary interviews with 17 experts in community engaged research, media professionals, and nonprofit/advocacy organization leadership. Members of our team conducted most interviews through a combination of virtual discussions over Zoom or Teams, though in a few instances, interviews were conducted in-person. The interviews were designed around a structured script developed by our research team to help ensure consistency across our discussions with experts. The script for these interviews is included in the appendix of our report. The interviews averaged an hour in length. Most of the sessions were audio-recorded, transcribed, and translated by team members, then analyzed. Anonymized quotes are included to highlight major themes that emerged from these semi-structured preliminary interviews.

- We hosted a series of roundtables with community organizations, researchers, government, and media participants. The main goal for the chosen range of experts and stakeholders was to wrestle with key questions of how research and data governance can be transformed to allow communities to take the lead, and of course, to inform our recommendations in the final report to ensure any possible hurdles (practical or policy related) were considered, and to clarify our findings. These discussions were guided by our team to ensure that robust and insightful conversations resulted in a deeper understanding of what was needed to enhance our model. The series of three discussions with experts allowed us to dive deeper into the questions we posed to the group, which would not have been possible with one session. Although we were able to sustain a core group of participants throughout the sessions, we invited fresh perspectives along the way to fill gaps in expertise or sector as we moved through the process. We conducted the stakeholder discussions in-person at The Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C. However, given the travel constraints for several of the participants who could not make it in person, we provided a mechanism for participants to join in these meetings virtually. These sessions lasted an average of two hours, and all participants were offered a small incentive to participate.

- We convened roundtable participants to discuss three main topics or themes:

- Defining a community-driven model for data governance

- Reflect on existing models and examples of data governance

- Reflections, critiques, and recommendations for a community-controlled, shared power model of community-engaged research to achieve data justice and equity

We describe the main findings from our landscape analysis and highlight the key points from our listening and learning process to present elements of what a new model for justice-oriented and equitable community-engaged research can resemble with the focus being on enhancing community ownership of this process to ensure a greater sense of data governance.

As a result of the background research and consultative process, we were able to conclude that existing research and data governance models can be transformed if funders, researchers, and community partners embrace important changes in research infrastructure. This includes adopting collaborative research behaviors and planning research projects with communities for the sustainability of research capacity to create impact-focused solutions, and contributing to ongoing research-community partnerships.

Even with the greatest intentionality and effort from funders and research partners, it takes time and consistent effort to develop a research and data governance infrastructure that promotes greater community data justice. We found that community control over research and data governance should be both structural and behavioral, which are more achievable under the following conditions:

- Funder and research partners should focus attention and commitment on practices, processes, human capital capacity, and funding streams with community partners to create a sustainable data governance ecosystem

- Researcher and community partners should prioritize practices that create an iterative culture of engagement that leads to a strong ethos of trust and power-sharing between communities and researchers

In addition, as we collaborated with our stakeholders, we were able to develop a community data justice model that confers authority over all dimensions of research design and data governance to communities as they engage with researchers, funders, and other partners engaged in community data collection. When fully realized, the concerted efforts of all three types of entities should lead to increased community capacity for communities to:

- Conduct its own research with or without research partners

- Shape the narrative that emerges from research and analyses

- Pilot community-generated initiatives to enhance particular or address specific concerns

- Sustain community research capacity and initiatives that emerge from research and analyses over the long term

A model that fulfills these conditions has the potential to enable communities to have more influence and control over data collection and governance than either researchers or funders, and is more likely to infuse research with new perspectives, as well as policy and programmatic recommendations, that could be meaningful for community members.

Most salient themes for a transformative model of community control

We examined numerous models and conducted several case studies of community engagement research and data governance. One of the limitations of these models and case studies, which provided the strongest examples of shared power with communities, was that communities were not in control of multiple important processes and resources related to the research endeavor.

As a result, we prioritized, both in our background research and in the stakeholder interviews and roundtables, discussions of the conditions that would be needed to shift the balance of power in data governance from funders and researchers to community control. Over the course of this project, several consistent themes about the responsibilities of researchers, funders, and community partners emerged. We summarize them below.

1. Responsibilities of researchers to advance community empowerment

If communities are to have more control over research and data governance, researchers and the institutions that house them will have to make a major cultural shift. Below are some of the most salient areas where the research community can make improvements to enhance the power and agency of communities interested in using research to advance their own agenda(s).

- Build trust with the community or communities with whom researchers intend to partner. This is a critical element and the foundation of shared governance within successful community engaged research projects. It requires time to develop a trusting relationship between researchers and the communities they partner with, which as we note, will require modification to the typical timelines attached to external research grants, and will also require researchers to invest in building the relationships in the community to conduct a truly transformative research model that promotes justice research. We heard from multiple researchers that have demonstrated experience with community-engaged research that the time required to truly get to know community leaders can be frustrating but that this is key to establishing trust.

- Engage communities in iterative negotiation at the onset of projects and along the way through research design and implementation. Agenda setting may be the most important, yet the least implemented aspect of the negotiation process. Engaging community leaders and stakeholders in the discussion of the challenges facing communities should occur at the start of the negotiations which will increase the community’s engagement in the full process and lead to research that directly speaks to their greatest needs.

- Formalize all of the outcomes of these negotiations with MOUs spelling out the data ownership and management within the relationship. We heard examples of where research institutions have taken important steps to cede power to communities by establishing formal MOUs to allow community advisory boards to oversee decision-making at institutes housed in their institutions.

- Train community researchers and data stewards to build infrastructure within nonprofit and community-based organizations. There are strong examples in our case studies of organizations providing research and data oversight training to organizations that they partner with that provide solid foundations for expansion in this area. This includes UnidosUS revising how they give out funding to community organizations that include community members on the committee that makes funding decisions following some basic training. We heard from their team that this has been an important but somewhat uncomfortable process, as it differed from their original model, which did not include community stakeholders. This is an important reminder that building a just community data model may be uncomfortable at times but can lead to great outcomes if all parties involved believe in the process based on mutual trust and respect established prior to the implementation of changes in the research process.

- Researchers should come from the communities (descriptive representation) being studied. When considering expanding in-house infrastructure within community organizations, identifying and training researchers from the community should be a priority. This is a critical aspect of sustainability; to sustain the investment in data governance, it is necessary to teach and train the next generation of researchers and those with lived experiences who are embedded in the community. These new researchers can continue to conduct community engaged research well beyond the initial project. We have learned from both our interviewees and landscape analysis that trust is enhanced when there is descriptive representation via the inclusion of a community member across all aspects of the data management and research process, making this an important yet often overlooked aspect of capacity building and building trusting relationships. Our interviewees noted the benefits of focusing training on young scholars to extend the long-term impact of this effort.

2. Responsibilities of funders to advance community empowerment

Our interviews with researchers and stakeholders highlighted the fact that funders can play an important role in increasing community control over research and data governance. Positively, several experts noted that they feel private foundations have greater potential to shift norms in research than the federal government and other funders. Below are some of the key responsibilities funders should take on to start to shift power towards communities.

- Provide a longer timeline for researchers conducting community-based funded research to allow for community engaged research approaches, such as building trust and recruiting and training community partners, which are time intensive. This was the most consistent suggestion made during our qualitative interviews, with many experts noting that the short timelines for funded projects are a major obstacle for the incorporation of community members and completion of projects. We recognize the challenge this may present to funders but want to stress the importance of trust-building and the training of community members in the data and research enterprise, all of which requires more time than typically allotted in contracts supporting research but would contribute to creating a community data justice model.

- Increase flexibility in the funding process to allow for the other principles we outline to come to fruition. Flexibility can be built into the process in many ways. It could include looking for paths to incorporate community members in the initial phase of research to allow the community to define the agenda or identify challenges they want addressed before a call is put out for research proposals. Funders could prioritize research that addresses solutions to the identifiable problems as opposed to solely studying the problem(s). It could include incorporating policymakers to ensure that data and findings are translated into applicable policy options. It could also include representatives from the media who could circulate findings or media trainings to allow for multiple avenues of dissemination. Flexibility should also extend to the final stages of the research process. Funding could be provided to allow community members to engage in each step of the funding and research process. The need to integrate media training for community members emerged as a particularly salient issue when speaking with our expert stakeholders. The following quote reflects the general sentiment conveyed by respondents.

“I like the idea of a speakers’ bureau for the community because the players may vary by community. I think there should be a partnership between the researchers and the community in working with the media as well. This would be important based on the type of media and goals.”

- Place funding within community organizations instead of research institutions and build capacity of community organizations through direct funding, whenever possible. Empowering community organizations to take the lead in the housing and dissemination of research funds will contribute to an important shift in power, as control of budgets and decisions related to funding is true power within research and data administration. However, providing this agency within community organizations may require direct funding to support the administration and staffing of community organizations, something we know is not the norm in traditional funding streams.

3. Community control of research design, budget, narrative, and application of data

In addition to the important changes in research practices that researchers and funders can undertake, community partners also have an important sphere of control in the community data justice model. The locus of community empowerment includes control or shared power in the development of the full research process, particularly the research design, focus of the study, application, analysis, and distribution of findings. In the traditional research model, shared decision-making over aspects of the research design process is not common, and more often relies on limited input from community stakeholders when making important decisions. In our extensive review of existing models, we found examples of community control over research and data governance to be extremely rare.

There are five areas where community partners can focus their attention when working with researchers and funders:

- Negotiate the research agenda and design. The first component is community control over the questions asked during a research project. We found that the traditional research model of researchers defining the research questions dominates, even in community-based participatory research. In our discussions and research, we identified one model (CLD3) that intentionally solicits ideas from communities, but that was an exception. Communities, therefore, should be able to negotiate the research agenda when working with researchers. If communities are able to define the questions being asked, community research is likely to be more responsive to community-identified needs and will be directed to help communities instead of serving to incentivize only researchers or intellectual inquiry. Additionally, this will provide an avenue to acknowledge and credit community members as co-creators and collaborative partners.

- Negotiate authority over the collection and use of community data. The second component is determining control over how data is utilized and disseminated. We determined that the control of data use is a strong measure of power in the relationship with researchers. In our analysis, we found very few examples of community control. There was one notable exception discussed in our case study of the Tribal research design process, which are projects that go through Tribal IRB review and requires Tribal approval of the research design and publication of research results. In this case study, Tribes have ultimate control over whether data is released at all and they have control over the narrative that is created using their data.

- Throughout our discussion with stakeholders, we heard from several nonprofit leaders that the inability to provide input on how the data would be used to improve the well-being of communities that they serve discouraged their enthusiasm for research conducted through partnerships. As one stakeholder remarked,

“We have never seen any benefit to the populations we serve with the research we have been asked to do. If we cannot tailor the research to answer questions we have internally about how to serve our communities, there is no real point to allowing researchers to work with our organization.”

- It is, therefore, important that communities are explicit about how they want their data collected and used and the mechanism by which permission to collect and use data is granted.

- Be prepared to connect with journalists and the media more broadly. As we conducted our discussions with stakeholders, we determined that an important element of community control over the use of data is the community’s capacity to share information with journalists and the media more generally and to shape the narrative about themselves and their community. Our media stakeholders noted that building effective relationships with journalists would improve the ability of communities to control the narrative associated with the data collected about them. This could include having trained community spokespersons creating data visualizations, authorized by the communities in question, to share with journalists via diverse media outlets.

- Negotiate research budgetary control. One of the most impactful shifts in community power toward community control would be to increase the ability of community organizations to oversee the budget for research projects. There was a near consensus in all of our qualitative interviews and roundtables that community stakeholders rarely have any input on decisions related to research budgets. This is a key limitation in the existing models of community engagement. As the structure of budgets reflects the priorities of any research effort, it is important to revisit the budget process and revise how funding decisions are made and who is provided with funds to conduct research. One suggestion is to formally require a community partner in the grant making process, which will push the balance of power in budget oversight toward communities.

- Request funding to build and sustain in-house research capacity. To achieve community control in the research design process, community partners will need to develop an enhanced research infrastructure. Community partners should have an opportunity to request funding to build in-house capacity for research within community organizations, so that communities can develop their own research independence and expertise from universities/researchers. Our roundtable participants uncovered some good models where research institutions train community researchers who have co-conducted focus groups and other aspects of data collection as formal members of funded research teams. This is part of the larger suggestion that community organizations negotiate the funding of the administration/staff of their organizations, which would be in addition to the research funding. The research infrastructure could include grant writers who can help sustain the project’s effort by pursuing other funding, including federal and state funds.

Abriendo Puertas – Opening Doors

Focus and mission of organization

The mission of Abriendo Puertas/Opening Doors (AP/OD) is to honor and support parents as leaders of their families and their child’s first and most influential teacher. Their work focuses on not only education (early childhood education being a core focus), but all policy areas that impact Latino families. Below are some of the areas they have focused on of late with policy advocacy

- Gun violence and mass shootings

- COVID-19/Long COVID

- Mental health of children and parents

- Paid Family Medical Leave

- Culturally & linguistically relevant quality early childhood development & education

Parent/community engagement anchors their work

The following excerpt from their mission statement makes it clear that their work aims to directly engage parents in their policy advocacy work. This is key, as community engagement is the foundation of their work.

“We believe that PARENTS are powerful agents of change in the lives of their children and communities. They lead the way to positive outcomes for their children.”

AP/OD parents participate in local programs to strengthen their leadership, knowledge, and support systems—all key in preparing their young children for school success. AP/OD has a well-known and respected curriculum they use to build parent knowledge and assist them in establishing a strong foundation for their children in reading, math, technology, health, and more. Parents support each other in making what they learn a part of daily life, understanding they are in powerful positions as leaders and advocates for their families.

Examples of family engagement in policy advocacy support our ideal model

We have learned the following from the comments made from AP/OD’s leadership during the discussion sessions and our in-depth interview with their director. The organization provided examples of several innovative approaches that are in line with the elements of our ideal model:

- They have partnered with university researchers to train parents in their network to conduct focus groups and administer surveys as part of their overall early childhood research and advocacy.

- They partner with research partners to conduct rigorous survey research that is blended with narratives from their families in their annual study of Latino families. This includes having parents present their stories alongside established researchers, which is a powerful combination.

- They use their national survey to provide specific policy recommendations in their core areas of focus, such as early childhood education and development. This research helps set the agenda for their advocacy efforts, which is in line with our goal of having the challenges for policy solutions based on community input.

- They have used this community-engaged research approach to successfully advocate for significant policy reforms across state and federal level policy domains. The best example of their impact is the recent constitutional amendment for early childhood education expansion in New Mexico, a product of decades of collaboration with other advocacy groups and researchers.

- Finally, they fill gaps in their infrastructure with partners who are aligned with their core values and mission. This includes communications experts who help with the translation of their work to policymakers and the media. They have also partnered with Brookings to conduct a webinar focused on long-COVID and with the Giffords Center for their work on gun violence advocacy.

Limitations of their existing infrastructure and opportunities for advancement

While this organization has many of the elements we have identified as being ideal for a community-grounded data governance model, their leadership has identified the need for continued advancement. When asked how their current power relationship with the parents and communities they serve is centered, Director Adrián A. Pedroza noted that they are roughly 60% to 40% with power in their favor but are working to integrate some innovations to get them to the 50-50 level. This includes hiring new project management and staffing capacity specifically focused on research that centers families in the policy work.

Areas where we can build their work with RWJF support

In our discussion with AP/OD about how we might be able to support their goal of reaching a 50-50 or greater relationship with their community of interest, Latino parents, the following opportunities emerged:

- Provide support to bring a research intern into the AP/OD staff. They have attempted to do this in the past with limited success. With Brookings oversight of the intern, there might be an opportunity to have this scholar work on increasing the research analysis of their existing data.

- Support the pursuit of external funds to conduct more research in line with the goals of the organization and the needs of parents. This organization is approached by researchers who are often interested in their curriculum or who are looking to gain access to their parent network. However, there is rarely a match between the goals and needs of the researcher and that of the organization. Some support from an outside team who can help identify external funding to support and sustain their community-engaged research goals would allow their team to continue expanding the engagement of their network in research efforts.

Indigenous data sovereignty and governance: Nuances to data collection and management for Native Nations/Native Americans

Summary of lessons learned

Our research included interviews with several Native American researchers who are experts in community engagement with Tribal communities, as well as the inclusion of Native American-focused work in our landscape analysis. This work makes clear that the unique sovereign status of Tribal communities in the United States requires a distinct model for these communities. This is matched with a growing global Indigenous data sovereignty and governance movement that is spurring greater attention and conversation, especially in the science community and among Tribal governments. In short, none of the frameworks that we referenced in our interviews, drawn from the landscape analysis, went far enough to meet the thresholds required to truly respect Tribal sovereignty and governance powers for data collection and ownership as communicated to us by our respondents. Below are some of the specific elements of conducting work with Tribes and Native American populations which were gleaned from that research.

For Tribes, data sovereignty and governance requires a much higher level of control than any of the conceptual frameworks or models point to. This includes Tribes ensuring that researchers are conducting research that is important and relevant to Native nations and communities (Indigenous data sovereignty) and requiring that researchers ask for formal permission to engage in research that specifically targets or recruits their members and go through a formal IRB process for Tribes that have that infrastructure in place. Moreover, many Native nations call for Tribal ownership of data collected on their Tribal members and in their communities (Indigenous data governance). These are all processes that can take much longer to complete than most funding cycles allow, requiring much longer funding cycles for researchers on external funding.

Tribes may also require reviewing any research reports, articles, or public presentations before the research findings are to be shared publicly. This is not something we came across for any other communities, which is unique to Native American research. This is foundational to the overarching principle that Tribes should own all data conducted on or in partnership with their community and control all decisions about how it is used.

Examples of Native American institutes/centers

Although the interviews we conducted with experts in Native American community-engaged research noted that there is not an existing research entity that oversees data management beyond their own individual Tribe, they did provide several examples of research entities that all have some aspects of the themes identified in our ideal model.

- American Indian Public Health Resource Center at North Dakota State University. The core mission of this organization is to respect Tribal authority, autonomy, and self-determination. This is the main principle stressed in our interviews with experts, and this organization appears to follow the best practices identified by those researchers. The organization addresses capacity building and supports community developed projects by providing culturally responsive technical assistance and other supports. They therefore approach research from a partnership perspective, critical for reaching the power balance we envision for the ideal model. The AIPHRC also provides Indigenous Evaluation training and resources for Tribal nations, agencies, and government entities. They can therefore be a resource to fill gaps in these areas for other research teams and Tribal communities.

- Johns Hopkins Center for Indigenous Health. This center has some of the qualities we envision in our themes for an ideal research center, including conducting sound research that advances the well-being of Tribes and the training model for Native American researchers interested in health research careers. Their long-standing relationship with Tribes is a model for others to follow, as this has allowed Tribes to help set the agenda for the research and helps ensure that research advances the direct needs of Tribes. This wasn’t always the case, as the center had to restructure how it interacts with Tribes and move to enhance descriptive representation, leading one of the experts we spoke with to have higher confidence in the organization’s ability to meet the goals we aspire to in our model.

- Native Nations Institute housed at the University of Arizona. A strength of this organization is their training capacity, as they offer technical assistance for a range of services including constitutional reform and strategic planning for economic development. For a fee, NNI will work with Tribes to ensure the work advances their goals.

- Native American Budget and Policy Institute at the University of New Mexico. Two of the most important elements of this organization that should be considered for wider adoption are to 1) have Governance Councils that have formal oversight powers of research entities focused on Native Americans. These are of a higher level than Advisory Boards, and in the UNM example, require provost level sign-off; and 2) train Native American students to conduct applied research that can be of benefit to their own communities.

Action steps suggested for research in partnership with Tribal organizations

Tribes often lack the internal capacity to implement the best practices for conducting research, making investment in this infrastructure a great opportunity for funders.

- Integrating students or young professionals from Tribal communities into research centers who can provide training could help increase the ability of Tribes to perform research independent of universities or other research institutions.

- There needs to be greater recruitment and training of a cadre of Native scholars who have the research and data skills that can partner and work with Tribes on data needs, challenges, and frameworks to advancing Tribal needs and interests around data.

- Engage Tribes in discussions of the most pressing needs in their communities that private foundation-funded research could help address and treat Tribes as partners in research.

- Respect Tribal IRB protocols and the best practices for conducting research with Tribes. We have included an example of steps to take when conducting this research.

- Prioritize researchers who have a track-record of working in partnership with Tribes in scoring research proposals, and especially researchers who may be from the community of interest to the research project.

- Establish Governance Councils in line with that created by the UNM Native American Budget and Policy Institute that oversees and sets the agenda for Native American-focused research centers.

- Finally, with additional resources, making wider connections across the ecosystem of community-engaged Native American research could help ensure that Tribal communities who lack the internal capacity to oversee data and research are connected to entities who may be able to support those efforts. This will take some training and enhancement of the research centers and institutes that are already doing this work to meet the increased demand.

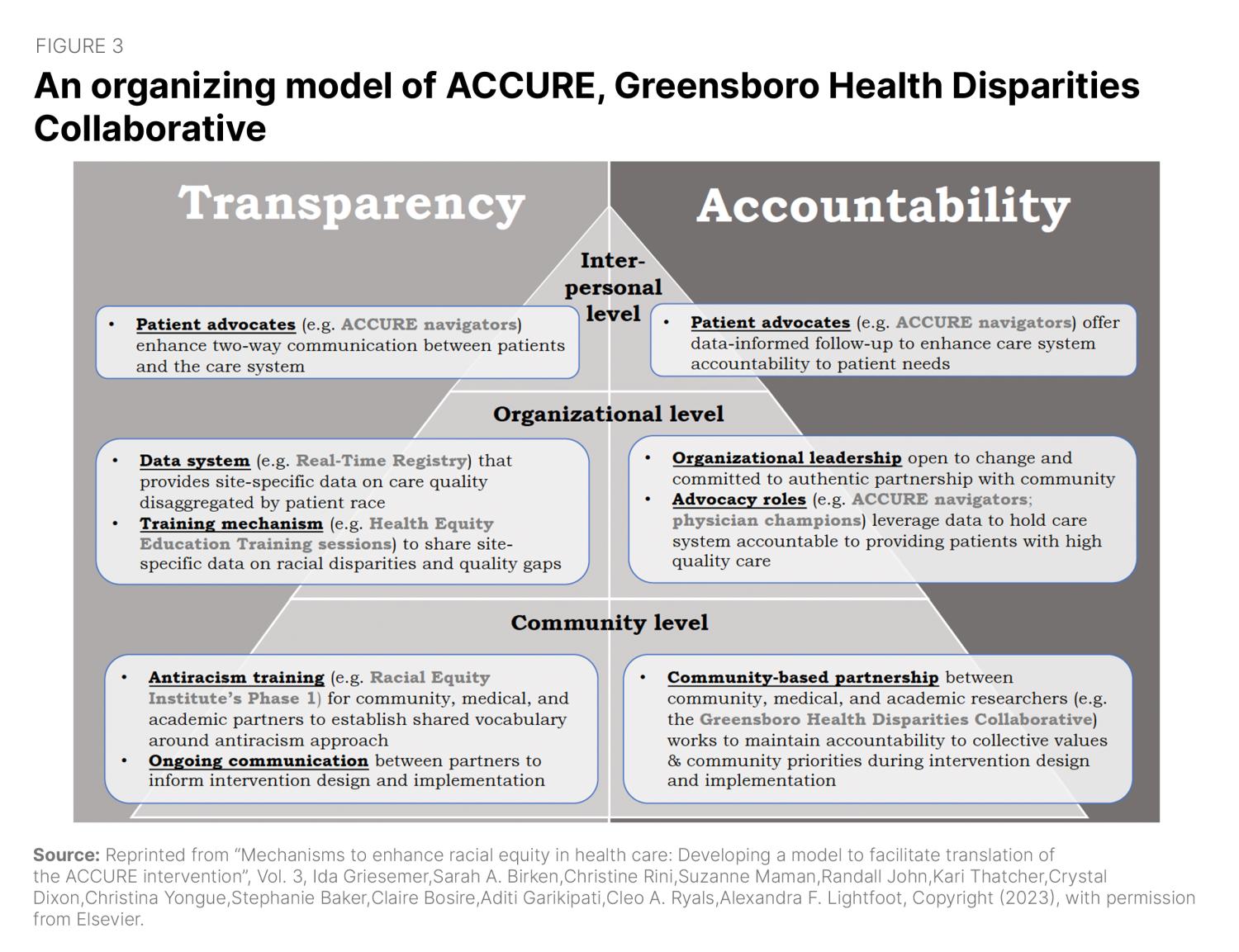

Greensboro Health Disparities Collaborative: Case study on anti-racism model

Organizational origins and mission

The Partnership Project (TPP) evolved from Project Greensboro, an anti-poverty initiative, that originated with the 1993 Mayoral Task Force on Crime. In 1996, Project Greensboro, Guilford College, and the City of Greensboro formed TPP, The Partnership Project, Inc.

After initially focusing on symptoms of community fragility, TPP was introduced to Undoing Racism training facilitated by the People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond. The racial analysis shifted the focus to addressing the root cause of systemic inequities, racism. The mission of The Partnership Project is to establish structures that respond to, empower, and facilitate communities in defining and resolving issues related to racial disparities.

Prompted by both personal experiences and the 2002 release of the Institute of Medicine’s meta-analysis Unequal Treatment, TPP secured an 18-month planning grant from the newly formed Wesley Long/Moses Cone Community Health Foundation (now Cone Health Foundation) to address racial health disparities with a racial equity lens. TPP organized and convened a group of Greensboro community members, medical system representatives, and academic researchers. Over many months, the members of this Health Initiative met for relationship building and mutual education before applying for a National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant to investigate racial disparities in breast cancer care as the Greensboro Health Disparities Collaborative (GHDC). Since the founding of the Collaborative, to become a member, everyone must complete a two-day Phase 1 Racial Equity Workshop provided by the Racial Equity Institute. This training centers on a historical analysis of structural and institutional forms of racism.

Approach: GHDC utilizes principles of anti-racism and a Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) approach to:

- Empower and facilitate opportunities for communities to define their own realities.

- Address and challenge the disconnect between research institutions and researchers and community members who experience racial inequities in their lives.

- Support co-learning opportunities for all members to grow in their understanding of racial equity including space for uncomfortable conversations about the history and current effects of racism.

- Support training and guidance to expand researcher-roles for community members.

- Facilitate and nurture a co-learning environment that embraces and manages necessary conflicts.

- Develop tools and lessons learned from projects to disseminate for other community-groups and to educate researchers about ways to engage communities.

- Support one another in community with a core set of values, principles, and processes of operation:

- In-person meetings begin with 30 minutes for food and fellowship time before formal business is discussed. Zoom meetings begin with 30 minutes of unstructured fellowship time.

- Addressing each other by first names creates equity in status among a diverse membership and helps build rapport, relationships, as well as bonds of trust.

GHDC tools:

- By-laws detailing how transparency in decision-making ensure community power is not eclipsed by academic/medical power.

- Dissemination Guidelines detailing equity in co-authorship and co-presentation to ensure community voices are not eclipsed by academic/medical voices.

- Full Value Contact signed by all members when they join, listing group-created common values, including the belief that every group member has value and therefore has a right and responsibility to give and receive open and honest feedback.

- Outreach Committee to provide continuing racial equity training updates to the full Collaborative at monthly meetings.

- Pinch Moment conflict accommodation for members to actively practice managing conflict and tensions when they arise.

- Financial Compensation Guidelines that detail support of GHDC and TPP as well as individual members endeavoring for equitable compensation for community members.

Developing and implementing an anti-racist path to public health research

Cancer Care and Racial Equity Study (CCARES) was funded by the NIH in 2006 to investigate why disparities between Black and white breast cancer existed. The project proposal was guided by a process established by GHDC.

- GDHC members completed a workshop focused on CBPR principles and approaches.

- Established a timeline and structure to respond to the NIH Program Announcement.

- Divided the grant writing tasks into 5-subgroups composed of one academic partner from UNC, one medical/health professional partner, and multiple members of the community. The subgroups were: Research Questions, Methods, Analysis and Dissemination, Proposal Reading, and Budget.

- Structured opportunities for storytelling and narrative building about experiences of racism in the health care system.

- Identified mechanisms in institutions that fail to foster racial equity to seek to understand how health care systems lead to inequitable health outcomes.

CCARES tools developed:

Accountability for Cancer Care through Undoing Racism and Equity (ACCURE), funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) was a multi-site system change intervention that utilized CBPR to reduce race-specific gaps in treatment initiation and completion for Black and white breast and lung cancer patients. The ACCURE intervention was based on the results from CCARES (described above). ACCURE integrated four innovations to implement the aims of the study:

- Training a nurse navigator to use a racial equity lens to identify and address practical, emotional, and communications issues for Black and white breast and lung cancer patients.

- Developed a real-time patient registry to alert the patient navigator in real time when patients did not meet nationally accepted treatment milestones and provided data to alert clinicians about race-stratified quality metrics for health care.

- Communication and collaboration with Physician Champions at each site to communicate race-specific clinical performance reports to physicians based on cancer type to ensure equity in the quality of care received.

- Provided Health Care Equity Education and Training (HEET) to medical and administrative staff at each study site to increase their awareness and accountability for patient care and patient outcomes through a racial equity lens and concepts of unconscious bias.

ACCURE tools developed:

Limitations and gaps in GHDC: All endeavors have limitations and challenges including GHDC:

- Fluctuation in membership has made it difficult to maintain a majority community influence.

- Embedding new people into an established collective is hard.

Recommendations to funders: GHDC’s successful model would suggest several recommendations to researchers and funders:

- Build in time at the beginning of an endeavor to get to know one another.

- Sharing a common language of analysis and an understanding that inequity was born out of centuries of racially constructed institutions.

- Researchers need to learn about the community and what drives their interest in research.

- Community members need to learn about what drives the researchers’ interest in investing time in this community.

- Address the pay ratio to provide equitable compensation for all partners.

- Understand that food and fellowship are tools to advance the work.

The Biocomplexity Institute: Case study of community learning through data-driven discovery model

Mission of organization

This intricate research institute offers a range of research opportunities and collaborations that investigate how living and non-living systems interact. The Biocomplexity Institute has married technological advances with systems-level thinking and problem solving. Their work focuses on the interactions between living and non-living systems from the molecular level to global, social, and economic systems. In a holistic way, the Institute also examines how the construction of social and economic systems and policies shape the spread of diseases through various community networks and how social services and systems are accessed and utilized. The Biocomplexity Institute identifies strategies to understand a mosaic of data sources, data infrastructures, and communities responsible for their production and management. The Institute utilizes the advances in computer technologies to help make meaning of the diverse range of data and finds unique ways to leverage this data for community members, nonprofits, government, and service organizations. This data is also important to aid in decision-making for scientists, policymakers, and leaders of service organizations.

Community learning through data-driven discovery process (CLD3)

The CLD3 model is a mechanism that integrates data science into communities to enhance decision-making at the local level. The CLD3 process liberates, integrates, and makes these data available to community leaders and researchers to tell their community’s story. The CLD3 process starts with research questions, discovering data sources to answer these questions, conducting exploratory analysis, and creating statistical models. Based on the statistical analyses and discussions with stakeholders, the cycle continues with proposing policy interventions and implementation of these interventions, including analyzing the interventions and updating policy. The cycle continues to monitor the outcomes of interventions, thus creating an adaptive feedback loop.

They have successfully tested scaling CLD3 through a partnership with Cooperative Extension Systems (CES) in Virginia, Iowa, and Oregon. A key feature of this work is to build the skill and knowledge capacity of CES professionals to help facilitate data-driven decision-making for the communities they serve. This program can lead to a larger National Community Learning Network. One of the advantages of working with a CES network is that they have a presence in every county in the United States. Each solution derived from individual projects and subsequent work can be scaled to a national level through the collection of these data, maps, analyses, and stories in a Social Impact Data Commons infrastructure. Project teams can assess the development and implementation of data-driven solutions and measure their direct impact.

The CLD3 model integrates four major premises:

- Continuous interactions with communities, stakeholders, and decision-makers.

- Developing, implementing, and assessing data-driven learning processes that understand the role of various forms of evidence and how it can be applied in real-world scenarios.

- Nurturing existing and new collaborations.

- Developing rigorous research frameworks that integrate theory, practice, and study designs to guide the scientific process.

The CLD3 model seeks to integrate data for analysis and evidence-based decision-making from sources across the social ecology in different forms. Some examples include:

Forms of data:

- Designed data, such as statistical surveys or designed experiments.

- Administrative data at neighborhood, municipal, county, state, or national levels.

- Internet sources, such as websites and social media and captured through application programming interfaces (APIs) and web scraping.

- Procedural data focusing on policies, and practices within organizations or for systems such as health care or local governments.

Examples of sources of data:

- Individuals, families, and community networks (deidentified), e.g., community conversations, and data walks.

- Designed data, e.g., U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey, Bureau of Labor Statistics Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics.

- Administrative data, e.g., local property data, fire-emergency medical services data (911), local and national food bank data, National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) births and deaths records.

- Internet data; Ookla speed test data to measure broadband access and availability; location of services to measure ease of access (catchment areas), e.g., urgent care and grocery stores.

- Neighborhood level data

- Food access

- Quality of neighborhoods and housing

- Neighborhood and community infrastructure

Across projects, Institute members assess data for its quality and utility to answer questions posed by stakeholders. Data are organized to facilitate management and analysis within a data governance framework to ensure there are ethics and accountability guiding data access, dissemination, and destruction.

The CLD3 model leads project teams through a process of ethical data access and use guided by principles of community-engagement. The examples of how the CLD3 model have been implemented across projects have developed a rigorous and repeatable process for others to engage in community-driven, solutions-oriented data science.

Literature Review

Overview

This community data governance project aims to reimagine the framework of data governance through the lens of data ethics, justice, and community-engaged research. Before we formulated our recommendations to achieve this, we conducted a review of various sources to provide a strong foundation to build upon. This includes academic journals, influential organizations, and key databases. We examined community capacity, data rigor quality, and perceived standards within research institutions to get an accurate understanding of this environment.

Landscape analysis of RWJF

This project is funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and a landscape analysis was conducted to get a baseline of understanding of the previous policies and practices initiated by this organization. This analysis will ensure our research will be utilized properly and is in-line with their expectations.

The focus of their work stems from centering communities, as their Sentinel Communities project highlights. Since 2016, they’ve monitored 30 communities’ efforts to promote health and well-being by providing reports showcasing community power, investment, and narratives. It reveals common qualities and practices in communities that others can learn from and implement themselves. This aspect was influential to our own project in how a system was developed to share successful strategies that uplift communities. Looking at research RWJF funds emphasizes their resolve to create structures for communities to follow and give agency back. Another such initiative they fund is the CDC Foundation’s program to improve engagement in community level data collection. The purpose is to accumulate community perspectives through focus groups, survey enhancements, community outreach, data collection, and information synthesis. What’s most compelling about these measures is that they help to put community voice at the forefront of the conversation. Our project further expanded upon this to create a blueprint for communities’ involvement to be centered in data ownership and throughout the research process.

Landscape analysis of methods

An analysis of the community-based participatory research (CBPR) method was conducted to understand the most common guidelines used to conduct this type of research. This method is a collaborative process that stimulates a community’s representation and contribution throughout the research process. At its basis, CBPR is transformative by empowering communities to integrate their expertise while maintaining ownership. This existing framework is rooted in the belief that communities must be centered in all stages of the research process for self-advocacy and determination. It has been a staple in research for decades and subject to evolve with greater discourse and community intervention. In 2013, a conceptual model of CBPR approaches was developed to improve community capacity with input from community organizations through focus groups. What this study confirms is that there is always room to expand upon the set interpretations of how community research should be conducted, and that community consultation is needed in determining the best practices for this research. Furthermore, the attributes of trust and power dynamics are ones we’ve found to be the most impactful within this model.

Additionally, on a global level, several frameworks have been utilized to analyze community-based projects, most notably the United Nation’s Human Rights Based Approach to Data which covers areas such as participation, privacy and accountability. It calls for developing communities of practice that improve the quality, relevance and use of data and statistics consistent with international human rights norms and principles in support of sustainable development. Nonetheless, there are still shortcomings that we aim to address and further develop to ensure communities are fully engaged in this process.

Methods we didn’t use

While exploring the most common methods for community engagement in research, there were several that stood out. These methods had their own unique focuses that provided a wider scope of what this type of research could look like. The frameworks seek to generate active participation and are organized in specific ways to reach this goal. Participatory action research is the precursor to CBPR in that it aims to have communities lead and inform the research process. Similarly, participatory rural appraisal specifically incorporates knowledge from the rural population in the development of projects. Many of the methods observed rely on the grassroots approach on this kind of specific stakeholder involvement to not only provide insight into the needs of the community but also for decision-making and overall evaluation. There are approaches to execute techniques like dialectical inquiry to combat group think and appreciative inquiry that utilizes questions and dialogue to help participants’ social engagement. What was also discerned was how the researcher’s perspective must be challenged to ensure local knowledge and practices aren’t undermined. This can then lead to empowering those previously marginalized by including structural elements of self-determination in the research design. These research approaches unveiled methods to center the community, and while not all-encompassing, they offer varying key attributes that are useful to consider for the project’s recommendations.

Common challenges and opportunities of CBPR

The CBPR research method offers a variety of opportunities that traditional research does not. Mainly, it allows researchers to treat community members as experts with valuable knowledge and perspectives. Community members are given the opportunity to transform their lived experiences into agents for deeper social change. The incorporation of ideas and solutions from those most impacted by the issue has the potential to bring forth collaborations between community stakeholders, governments, and researchers. This method promotes shared vision, community ownership, and greater opportunities to coalesce around particular issues. Through tapping into the assets of communities and emphasizing their strengths, CBPR is an avenue of community empowerment and capacity building. Participants are enabled to develop problem-solving abilities and take greater control over the issues plaguing their community. Researchers develop a deeper understanding of the community and are enabled to develop better research designs for their studies. CBPR’s basis of respect and partnership with community members often makes it a more ethical and democratic approach than traditional research.

The complex nature of relationships, power and accountability within CBPR creates a unique set of challenges. The time it takes to develop the trusting relationships CBPR requires can be difficult to align with funding timelines, group calendars, and community expectations. CBPR work can require high levels of emotional and intellectual energy from participants and disrupt their personal lives. Researchers are forced to balance the power and vulnerability of themselves and the community they are working with. Further, researchers must understand the culture of the communities they are working in to ensure their work will be ethically and culturally appropriate. In some cases, challenges can arise in defining what constitutes a community or resolving conflicts between individual and group interests. CBPR studies are difficult to fit into thr International Review Board’s research frameworks that dictate clear distinctions between researchers and researched. Additionally, modifying informed consent in the context of community is required since studies often require individual consent to participate. What’s more, resource constraints present an added challenge. Community-based organizations typically have limited time and staff to invest in these partnerships and often rely on external research-based institutions. Beyond this, there is often an uneven balance of financing which reinforces the power imbalance between CBOs and research institutions. The latter typically serves as the primary source of funding while the CBO assumes a dependent role on that of a subcontractor.

Future areas of research

Trust is a fundamental aspect of community-based projects. However, there is a lack of an understanding of the process, stages, tools, and best practices to not only develop and manage the challenges and conflicts of the relationship but also how to measure the level of trust over the course of the project. Nevertheless, there is existing research to further explore how to build and measure an operational definition of partnership trust over the lifecycle of the project.

Best practices with the media

An often-overlooked aspect of research is its connection to media relations. When deciphering the most important elements of a research project, it was evident there was a glaring lack of development in dealing with the media. This is cause for concern given how useful a tool it can be for increasing the impact research can have. Utilizing the media can promote public awareness, inspire more work, and ensure future funding. Most importantly, having the power to disseminate information is a key construct within community-based research. The strategies of best practices with the media enable self-sufficiency in this field. These strategies include preparing a press kit and passages to help set the agenda, building relationships with reporters, and setting the narrative through a positive lens. Understanding how vital media is in relation to research allowed us to ask questions from experts to further this connection and create substantial procedures that can be implemented.

Data collection in communities

Going into this research, a central question we aim to answer is how can communities collect their own data and maintain ownership? Not all communities can house their own data, so it’s important to establish strategies that lead to greater transparency and easy access to information. This led us to distinguish between various applications that disseminate such information. Understanding data literacy is a key component of data communities that seek to foster engagement and collaboration. A data community is the instrument to provide access to potential partnerships and valuable assets. This element of data sharing can make a significant impact on communities who would benefit from this strategic investment. A study was done to examine the National Institutes of Health’s policy for data sharing, and it highlights that community perspectives increase benefits for all parties. The study focuses the crux of the issue on how data is vital to the scientific method and that when done properly, the distribution of data enhances the research process across the board. Data dashboards are also a useful tool that offers a unique way for researchers to support community engagement. The infrastructure enables community partners to disseminate information and explore other avenues of thought through data visualization, intuitive functions, and enhanced communication capabilities. The application of these various principles implores that access and ownership of data is a vital aspect to all research. It’s necessary then to ensure this is a focal point when reimagining the framework of data governance.

There are existing databases that embody these principles and take actionable measures to increase transparency and collaboration. In examining the Community Commons Database, this robust platform provides tools, resources, and data in an organized fashion, curating a network of support. Similarly, the National Equity Atlas from PolicyLink informs community action by democratizing data and advancing equitable growth. These platforms showcase how aspects of data visualization and data capacity encourage engagement. They are highly receptive, produce quality work, and initiate analyses for communities to have greater agency. Discerning what applications work the best in these databases allows for replication on the scale we aim to use.

Community committees

Community committees exemplify how uplifting and supporting members of a community can create positive change. Stemming from lived experience and personal affiliation, this showcases that those with a direct link to the problem are the most qualified to initiate solutions. A group of committed leaders can have the power to center the community’s voice when there are compounding factors that have systemically disenfranchised entire communities. In 2014, The Ferguson Commission was created in response to the death of Michael Brown Jr. and the unrest that followed. The Commission, composed of 16 community volunteers, evaluated the institutional conditions which enabled such flagrant disregard for human decency and engaged with the community and experts to develop a deeper understanding of the impact of these conditions. The subsequent report details actionable policy recommendations to ensure equitable practices are upheld. This is an example of what strategic community leadership can accomplish when there are resources to enable change.

Tribal data sovereignty

Indigenous People are visionaries of data sovereignty, essentially altering the landscape of community-based research as we know it. They must set their own agenda because they know they can’t rely on third parties to accurately represent their interests when they’ve been historically oppressed by said entity. The First Nations Principles of OCAP goes further to expressly establish that all First Nations’ data and information only belongs to them. This is a model stating that ownership, control, access, and possession of all data will be aligned with First Nations’ traditional knowledge, principles and protocols. This explicitly outlines how data sovereignty plays a role in empowering marginalized communities and uplifting them to create boundaries that protect against exploitation.

Successful Tribal data sovereignty is applied worldwide, in which capacity for agency is incrementally restored. For instance, in New Zealand, Te Atawhai o Te Ao is an independent Māori research institute whose guiding principles are to generate and rediscover knowledge through a community lens. Their identity is a staple of their research and autonomy to produce and have ownership over their work. This has led to projects that reflect the community’s needs, such as a survey of Māori experiences with racism that can influence real policy change. In Alaska, collaboration between the Alaska Native Tribal Consortium (ANTHC) and Alaska Pacific University (APU) has formed the Alaska Indigenous Research Program (AKIRP) to address the needs of Alaska Native and American Indian People. From a culturally conscious framework derived from Alaska Native elders, the program provides Indigenous-centered, cross-cultural health research, education, and training in Tribal health. Much can be learned from these two extraordinary examples of how Tribal sovereignty has evolved and continues to shape the research field. Importantly, they feature how the ideals of data privacy and control are attainable and do have an impact on the community.

Limitations

While the examples in this review offer ample positives, there are limitations to what has been achieved. As an overview, the literature doesn’t adequately delve into the root of key issues, in which there is no greater understanding of what infrastructure is needed within this field, hindering the success of generating intersectional change. For example, the methodologies previously mentioned state there should be more community interaction in the research process, yet they offer no structures to support the investment of this or tangible community ownership. Having formal agreements at the onset of the research process will ensure communities have legal recourse and a lasting relationship. A main point within this type of research is how data will be collected, stored, and implemented. The literature provides examples of this, yet there are no concrete steps on how to exactly achieve this. There must be technology experts in-house that can create and maintain these databases to continue the work of communities. Additionally, it’s not enough to just have certain tips in dealing with reporters or the media, there needs to be an infrastructure of media training. This is not typically seen as a priority but it’s a valued skillset to acquire and establish so the research can be accurately presented and disseminated to a wider audience.

This work is based on centering communities, and as the literature shows, there are many communities that have re-established their agency in some capacity. Within these communities’ journeys they’ve had to prioritize their own needs over others. In the future of community data governance, sharing strategies on how they were able to be successful with other entities will help to broaden these equitable practices on a larger scale. We aim to have a deep and lateral understanding of what the necessary steps and requirements are to establish communities as the focal point in all elements of the research process. Using the best pieces of previous models, ideals, and practices, learning from them and building upon them will guide our framework to create a model that is inclusive and thorough.

Conclusion

From this literature review, we’ve gleaned an initial understanding of what’s most important to include in an enhanced model that advances the community in all facets of the research process. The most essential aspect that all examples of the literature embody is giving agency and power back to exploited communities. This is a defining piece of what it means to do community-based research, regardless of the different capabilities needed to usher in results. The avenues we explored sought to shed light on what’s been working in community-based research, but most importantly, what’s missing. Our project expanded on this by various means to recognize these gaps in the literature and then curate a multidimensional model.

Scripts used for our stakeholder interviews

Questions asked in our preliminary interviews:

Part 1

We would like to get started by having you tell us a bit about your thoughts about and/or experience with community-engaged research intended to capture the opinions of hard-to-reach communities who are often marginalized or mis-represented through traditional research.

- How did these relationships develop and become sustained?

- Are there a set of principles you use to guide your community partnerships?

- What challenges have you encountered in building trust and rapport between researchers and community members, and how did you manage them?

- What best practices have you used or come across that nurture mutually respectful and beneficial relationships?

- What principles have you seen in partnerships that successfully move from infancy to more mature long term?

Part 2

Our project is centered on understanding best practices that can lead to more equitable partnerships, particularly how we think about evidence and/or generating data to solve complex social, economic, and health challenges.

- When you hear the idea of an equitable data infrastructure or equitable data sharing models, what comes to mind?

- What models of equitable data collection and shared governance can lead to better represent and be more inclusive of the lived-experiences, voices, and opinions of marginalized communities?

- In particular, who should always be at the table?

- One component of this project is to identify a list of best practices, resources, and narratives that help to highlight what is working. If you have any examples of conceptual models or any best practice-oriented thoughts that you may want to share with us, it would be much appreciated.

Part 3

Let’s switch gears and talk about how community engaged research is supported or hindered by policymakers, media, and other stakeholders who use or communicate about data to broader audiences.

- What are your experiences working with policymakers to either collect, analyze, or communicate about data?

- Our background research has suggested researchers may have some challenges getting policymakers to understand that data not collected more traditionally (random samples etc.) has value, have you had any experiences with this in your work or heard about this from colleagues?

- Given the challenges you have outlined, what are some of your thoughts on how to ensure that data generated at the community level is considered seriously by a variety of audiences?

- What has been your experience working with media teams, media outlets, or journalists, to either collect, analyze, or communicate about data?

- Do you think the press has any biases toward community engaged data or narratives generated by communities?

- Finally, are there any other suggestions you have for us that you feel could help improve the prospects of addressing social inequalities through better data collection for marginalized communities?

Questions asked in our post-roundtable interviews:

- As you know, we are looking to build a new model for conducting research that puts the balance of power with communities. Based on a goal of having more than 50% of power in a relationship with the community, where do you see your organization/organizations as a whole, on that spectrum? What steps do you think will need to be taken to get to that next level and what aspects of your current work do you think is already there?

- What do you think the ideal power balance should be between communities and researchers and research institutions?

- If you were to envision a new center or institute that would truly put power with the community, what would that look like to you?

- Reflecting on your past work, what advice can you offer to help other organizations that are trying to emulate the same work as you?

- What best practices have you come across in building trust and rapport for a successful long-term relationship?

- Finally, can you point to any policy outcomes that have resulted at least in part from your team’s work that has already improved the lives of families or that you project to improve outcomes for the wider community?

Author section