I keep winding up in Oxford, Mississippi, sometimes for business but always for pleasure.

The first time I visited, in 1987, I was a reporter covering the debut of the commemorative William Faulkner stamp (the Postal Service likes to do these ceremonies in the subjects’ hometowns). It was a big deal, not least because the Postal Service was eating considerable crow: Surely Faulkner is the only commemorative subject who was also once fired by the Postal Service, as he was in 1924 (provoking his declaration that never again would he “be at the mercy of any s.o.b. who had two cents for a stamp”).

There were lots of Faulkner scholars underfoot, and Eudora Welty gave a reading. And every surviving Faulkner relation showed up. Even Faulkner’s only child, Jill Summers, made an appearance. I was poking around Rowan Oak, Faulkner’s home, and chatting with the curator when she came in alone, went upstairs for about an hour, and then left. The curator told me it was the first time she’d been back since her father’s funeral in 1962.

566032779

Downtown Oxford at twilight.

Carolyn Cole/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

It’s tempting to ask rhetorically how could she possibly stay away from such a charming town, because Oxford’s been luring me back again and again since that first visit, sometimes for work, sometimes just for fun. But then, Jill Faulkner’s experience growing up there was quite different: For one thing, her father, when he wasn’t writing prize-winning novels, was a solitary binge drinker with no time for niceties like his daughter’s birthday party (“Nobody remembers Shakespeare’s child,” he told her on one such occasion). More humbly, but with far more import for day-to-day life, her daddy detested modern appliances, refusing to allow even a radio or an air conditioner in the house (in Mississippi!). And never mind a television set. To watch his favorite TV show, Car 54, Where Are You?, he walked over to a neighbor’s house.

In Oxford, it’s hard to escape the long shadow of the Nobel-prize-winning creator of fictional Yoknapatawpha County (there was a food truck in town for a while called YoknapaTaco, and there’s an apartment complex, one of dozens ringing the old town, that some not entirely Snopes-like developer dubbed Faulkner Flats). If there were a literary equivalent of Zillow, Concord, Massachusetts might rate as the number one town in America for authors per square foot, having bragging rights to Emerson, Thoreau, and the Alcotts. But anyone who’s fallen under Faulkner’s spell, even a little, can’t visit Oxford without immediately trying to match incidents in his books with actual locations. For anyone who needs help, the local tourist office has created a walking tour brochure (there’s where Gavin Stevens’ law office was once located, or at least where it was set in the film of Intruder in the Dust; that’s the house that modeled for the Compson mansion; and of course, in the center of everything, there’s the town square where Benjy was driven the wrong way in The Sound and the Fury). There’s even a little life-size bronze statue of the author sitting on a bench facing the square.

So Faulkner is hard to ignore. But not impossible. Not like football in the fall.

Ole Miss football might as well be another religious denomination, given the fervency with which it is worshipped by the faithful, i.e., the alumnae. The day in December when the next fall’s schedule is announced, hotels get booked almost immediately (and prices skyrocket). If you do not like football, you want to avoid Oxford in the fall.

The Lyceum, oldest building on the campus of the University of Mississippi.

Wesley Hitt/Getty Images

But if you get trapped as, say, the significant other of a rabid Rebel football fan, what are your options? Given that this is a college town, and college towns, especially in red states, have more in common with other college towns than with neighboring towns and cities, your options are much better than you might expect.

Oxford has changed a lot in the last few decades. The Oxford I first saw in the ’80s was a sleepy little Southern college town built around a courthouse square with its requisite statue of a Civil War foot soldier, no memorable restaurants or hotels, and one very good bookstore. It had more in common with Faulkner’s Oxford than what’s there today.

Oxford is still a small town, but you wouldn’t call it sleepy. The extraordinary bookstore, Square Books, is still there and has three satellite stores dotting the town square. There’s also a terrific new & used record store, End of All Music, located above a lady’s clothing store on the square. (I told you it was a college town.) If you get thirsty and want to have a little fun, there are a couple of speakeasies in town, by which I mean bars with slightly secret entrances. Nightbird hides inside the Oliver Hotel, and Bar Muse is at the Lyric Theater.

Or go right to the source, because now Oxford can boast North Mississippi’s first distillery: Wonderbird, located on the edge of town, produces a subtly flavored product that could make you redefine your idea of gin–in a very good way. They’re not open for tours, and they don’t sell their product on the spot, but they do schedule tastings and special events from time to time, so maybe you’ll get lucky.

And these days there are enough good restaurants to qualify the place as a foodie destination.

City Grocery has been feeding happy diners in its location on the town square since 1992. And it has spawned several offshoots, including Big Bad Breakfast (where given my druthers, I’d eat three times a day), and most recently Snackbar. The only thing wrong with that place is its name: it looks and feels nothing like a snack bar and every which way like a first-class restaurant that does simple (fresh oysters) and complex (Royal Red Shrimp Cakes—corn cakes from the griddle that make you dream of heaven) with ease. Put it this way: I hate most slaw (what kind of word is that—slaw? It sounds like half a Tolkien villain), but I would eat Snackbar’s slaw any day. And you don’t have to fine dine to eat well in Oxford: Handy Andy will sell you a great barbecue sandwich and give you change for a ten.

What draws us to a place? Surely there is no set recipe or checklist, no one size fits all. Lovers of big cities may embrace Chicago or Paris but not both? Is your idea of a cool beach town Newport or Galway or Myrtle Beach? And sometimes places sneak up on us, as Oxford did on me. I’d been drawn back three or four times before I realized how fond I’d become of this small town stuck up in the hill country of northern Mississippi.

I know a handful of people in Oxford, which always helps. It’s not too big to get lost or too small to get boring (although it is getting bigger scary fast: the town’s population, currently around 25,000, has almost tripled since 1990). Summers can be brutal, but the rest of the year is temperate. And I’m Southern, which may matter most of all. In Absalom, Absalom!, Quentin Compson, Faulkner’s poster boy for sensitive young Southern males, mulishly insists, “I don’t hate it! I don’t hate it!”, when asked by his Canadian roommate at Harvard to “tell about the South.” First reading Quentin’s declaration when I was about his age, I thought, you and me both, pal.

If hate were all there was to it, it would be easy not just to tell about the South but also to then ignore it. But that’s only half the story. As Oxford’s most famous resident once observed, the past isn’t dead; it’s not even past. This is the South in a nutshell. Good and bad, past and present, all vie for primacy.

At the heart of the Ole Miss campus, the Lyceum, a stately old Greek Revival building, still shows the bullet holes from the 1962 riot protesting the enrollment of James Meredith, the first Black student to enroll in the university. Two people died in that riot between 3,000 armed citizens opposing segregation and federal forces that included U.S. marshals and the National Guard. But a literally scarred campus is not the only reminder of that dark time: on the plus side, a statue of Meredith also stands on campus to commemorate that watershed moment when segregation lost a crucial battle (one Mississippi politician plausibly called it “the last battle of the Civil War”). And here again, the record over time is complicated: the school ditched its noxious mascot Colonel Reb years ago, and Confederate flags are no longer ubiquitous at sporting events, but the football team is still called the Rebels. What the hell?

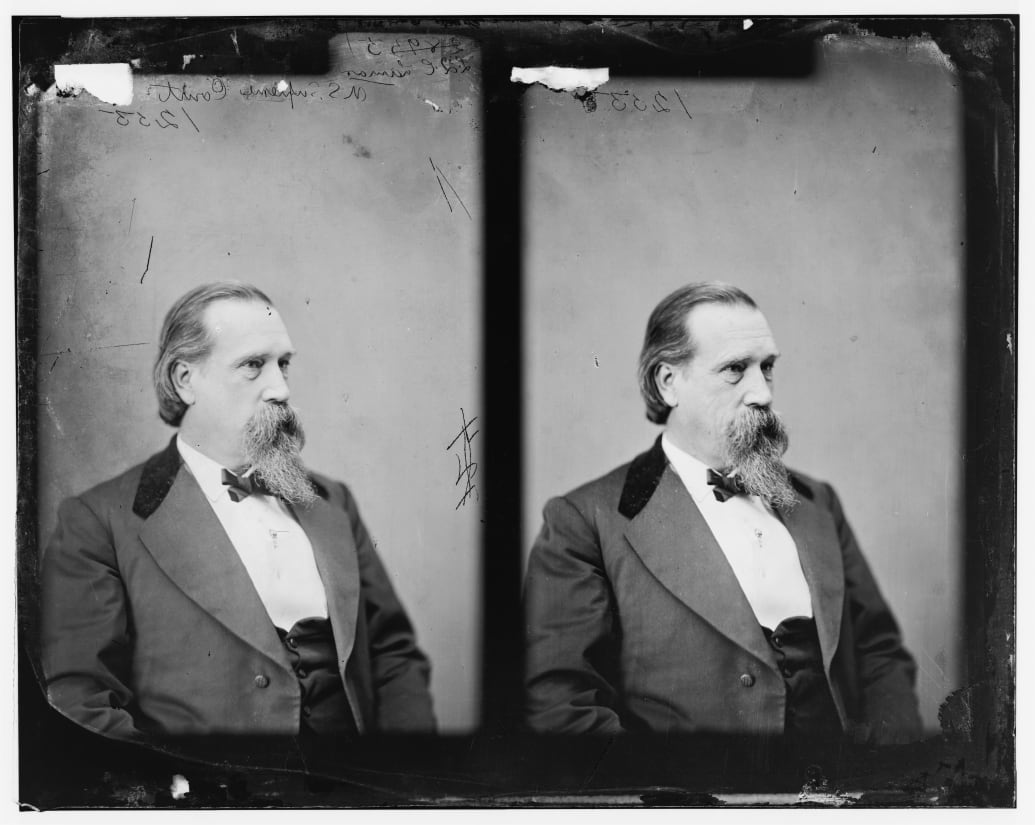

L.Q.C. Lamar epitomizes both the good and bad of Mississippi life.

Heritage Images via Getty Images

No one epitomizes the good and bad of Southern life better than L.Q.C. Lamar (1825-1893), an Oxford resident who served the Union, then the Confederacy, and then the Union again as a U.S. representative, a U.S. senator, secretary of the interior, and as a Supreme Court justice. Somehow he also found the time to practice law, farm, and teach math at the university. He was also a slave owner, a defender of secession, and Jefferson Davis’ emissary to Russia during the Civil War (he never made it as far as Russia and spent most of the war trying unsuccessfully to persuade European powers to ally with the Confederacy). But after the war, he also lived long enough to recant his opposition to Reconstruction and to embrace the idea of Black suffrage and the cause of Black education.

You don’t have to agree with John F. Kennedy that Lamar deserved a spot in Profiles in Courage to admit that he was a complicated man, capable of enslaving other humans but also able to cop to his sin. I’m not sure Faulkner ever gave much thought to Lamar, but maybe he did, because Lamar’s story and that of so many other Southerners fit Faulkner’s definition of the crux of all art: the human heart in conflict with itself.

Granted, that’s a heavy formulation to load on a little Southern town, but it’s that craziness, the knowledge that sense and nonsense co-exist inextricably, that I crave in places, particularly in the South, the place where I feel the least not at home. Oxford and its North Mississippi hill country environs don’t have a patent on that kind of crazy, but crazy certainly has a home there. You hear it in the literature, and you hear it in the music: North Mississippi blues—think Fred McDowell, Otha Turner, or R.L. Burnside—doesn’t sound like any other blues; it sounds like someone casting a spell, and a strong spell at that, a spell I’ve been under for quite some time.