The known: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are disproportionately affected by kidney failure but are less likely than non‐Indigenous Australians to be waitlisted for and to receive kidney transplants. Poorer outcomes have been cited as a reason for the disparity.

The new: Deceased donor kidney transplantation provides a clear survival benefit for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians eligible for transplant waitlisting compared with remaining on dialysis.

The implications: Our findings support prioritising and promoting waitlisting of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who are otherwise eligible for transplantation.

Historical and current colonisation practices lead to poor health outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.1 Kidney failure is one of many chronic diseases that affect a larger proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people than non‐Indigenous Australians; the kidney failure rate is more than three times as high.2 Kidney transplantation provides better survival outcomes than remaining on dialysis for people with kidney failure, particularly young people.3,4 However, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are far less likely to receive kidney transplants than non‐Indigenous people;4 in 2019, 14% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who required kidney replacement therapy received transplants, compared with 50% for non‐Indigenous Australians.2

The major barrier to transplantation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is being waitlisted. Non‐Indigenous Australians are far more likely to be waitlisted than Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.5,6 The difference is not explained by patient‐ or disease‐related factors,5 indicating that other factors are involved. A perceived lack of benefit has been cited by health professionals as contributing to a lower waitlisting rate.7 Comparisons of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non‐Indigenous kidney transplant recipients have found that outcomes were poorer for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people,8,9,10 leading to uncertainty among health care providers, and caution in promoting transplantation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.7

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are intensely interested in kidney transplantation and consider it the treatment most likely to allow them to return home and resume a normal family and community life.11 However, they feel ill‐informed and disempowered about pursuing transplantation as a treatment option.11

Given the disparity in kidney transplantation rates and uncertainty regarding its benefit, we compared the survival benefit of kidney transplantation and remaining on dialysis for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people eligible for transplantation.

Methods

Aboriginal community engagement and research governance

The Aboriginal Kidney Care Together Improving Outcomes Now (Akction) collaborative research group organised a series of community consultations with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living with kidney failure, their families, and carers in urban, regional and remote communities in South Australia.12 Transplantation was identified as a community priority.13 The Akction reference group worked with the research team to guide and govern the research process, including the engagement as investigators of two Aboriginal people who have experienced kidney failure (authors KO, RL). The findings of this study were reviewed by the Akction reference group, who guided interpretation and provided a strong message on the implications for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities (Box 1).

Data sources

In our retrospective national cohort study, we analysed linked data from the Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant (ANZDATA) registry (https://www.anzdata.org.au/anzdata), the Australia and New Zealand Organ Donation (ANZOD) registry (https://www.anzdata.org.au/anzod), and OrganMatch, a database administered by the Australian Red Cross, which maintains the kidney transplant waiting list (https://www.donatelife.gov.au/for‐healthcare‐workers/organmatch). The linked dataset facilitated accurate assessment of transplant waitlist status for individual people over time.

The study included all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults (18 years or older) who commenced dialysis in Australia for the first time and were placed on the deceased donor kidney transplant waiting list at any time during 1 July 2006 – 31 December 2020. We excluded pre‐emptive (ie, prior to starting dialysis), living donor, or multiorgan transplant recipients.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was relative survival after kidney transplantation, compared with remaining on dialysis, as indicated by the hazard ratio for death, unadjusted and adjusted for selected demographic and clinical factors.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted in Stata 17. Baseline characteristics are summarised as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs), means with standard deviations (SDs), or numbers and proportions. Data were censored at the end of follow‐up (31 December 2020), loss to follow‐up, or receipt of a living donor transplant. Follow‐up was not censored at removal from the waiting list or transplant graft failure and return to dialysis; people in whom grafts failed were retained in the transplant‐received group. Summary statistics exclude people for whom data were missing in the relevant categories (

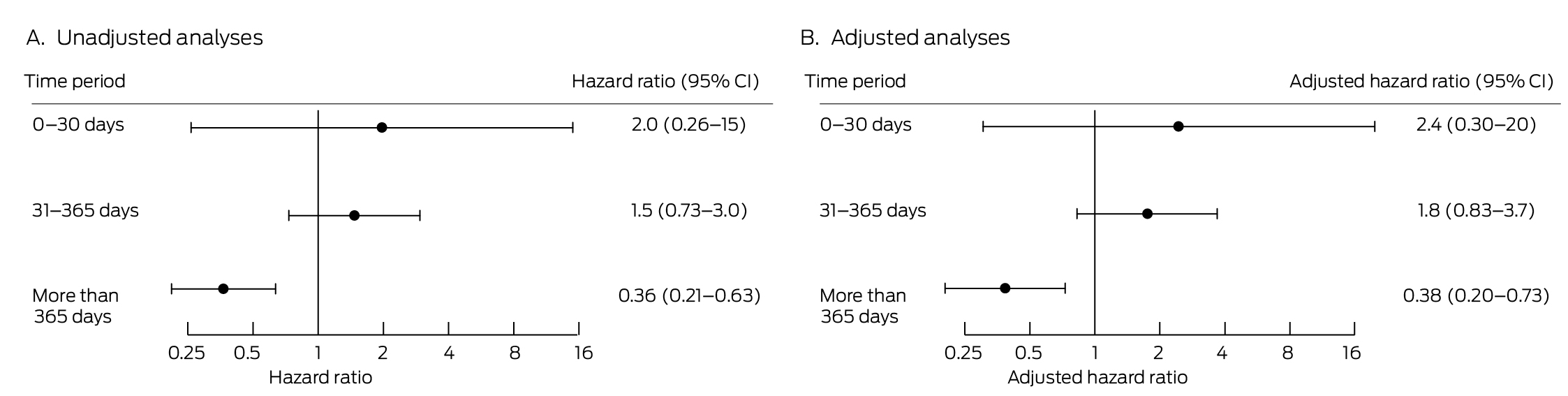

Survival was assessed in piecewise Cox regression models in which transplantation was a time‐varying exposure. The risk of death initially increases after transplantation because of surgery‐related risks and early intense immunosuppression, but declines in the longer term.3 As the risk is highest during the first month and remains elevated for about twelve months, treating transplantation as a time‐varying covariate led to violation of the proportional hazards assumption. We therefore divided post‐transplantation follow‐up into clinically relevant periods, allowing us to account for this violation: less than or equal to 30 days, 31–365 days, and longer than 365 days.

We explored interactions between kidney transplantation and age, gender, body mass index (BMI), diabetes, remoteness of residence (Australian Statistical Geography Standard14), and late referral to nephrology services (within three months of commencing kidney replacement therapy). We undertook multivariable analyses adjusted for age, gender, BMI, diabetes, late referral, coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic lung disease, smoking status, time to transplant waitlisting, geographic region of residence (remoteness and state/territory of initial dialysis centre), mode of dialysis (haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis), cause of kidney failure, and era of care (to account for changes in practice: 2006–2010, 2011–2015, 2016–2020). We report hazard ratios (HRs) and adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) for death with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We also prepared Kaplan–Meier style curves to visualise survival differences over time acknowledging that due to movement of people between the dialysis and transplantation groups throughout the study period, the interpretation of these require caution.

To assess whether changes in survival after deceased kidney transplantation were similar for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non‐Indigenous kidney transplant recipients, we repeated our analysis including non‐Indigenous Australians, applying the same inclusion and exclusion criteria. In this model we stratified by ethnicity and included interaction terms between ethnicity (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander vs non‐Indigenous) and each of the other terms in the model, and tested the joint significance of the interaction terms between ethnicity and post‐transplant status.

Data sovereignty and ethics approval

Data on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples collected by the ANZDATA registry remain the property of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community. The Royal Adelaide Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee has approved the operation of the ANZDATA registry (HREC/17/RAH/408R20170927). Our study was approved by the ANZDATA Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health working group, the Aboriginal Health Research Ethics Committee (South Australia; 04‐19‐848), and the University of Adelaide Human Research Ethics Committee (34486).

Results

Of the 4082 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who commenced dialysis during 1 July 2006 – 31 December 2020, 450 (11%) were waitlisted for deceased donor kidney transplantation and followed up for a total of 2927 years (Box 2). The median age at the commencement of dialysis was lower for waitlisted people (44 years; IQR, 34–53 years) than for those who were not waitlisted (53 years; IQR, 45–61 years); the proportions with selected other medical conditions were smaller for waitlisted people than those not waitlisted, as was the proportion living in remote or very remote locations (173, 38% v 1854, 51%) (Supporting Information, table 1).

Of the 450 people waitlisted for transplantation, 323 (71.8%) received deceased donor transplants. The median age at the commencement of dialysis was similar for people who received transplants (43 years; IQR, 33–52 years) and those who did not (47 years; IQR, 35–54 years); a smaller proportion had coronary artery disease (44, 14% v 29, 23%). Median time to waitlisting was longer for people who received transplants (733 days; IQR, 350–1431 days) than for those who did not (618 days; IQR, 350–985 days); the median time from commencement of dialysis to transplantation was 1083 days (IQR, 659–1902 days) (Box 3). Forty‐one people who received kidney transplants (13%) died during the follow‐up period; three were lost to follow‐up. Thirty people who did not receive transplants (24%) died; none were lost to follow‐up (Supporting Information, table 2).

Transplant survival

Deceased donor kidney transplantation conferred a significant survival benefit for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people waitlisted for transplantation from twelve months post‐transplantation (Box 4). In the immediate post‐transplantation period, mortality was comparable between the two groups; first 30 days: HR, 1.97 (95% CI, 0.26–15.2); between 31 and 365 days: HR, 1.47 (95% CI, 0.73–2.93). After this, there was reduction in relative mortality (beyond twelve months: HR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.21–0.63). This benefit persisted in the adjusted analysis (aHR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.20–0.73), and there was no significant interaction with age, gender, BMI, diabetes, remoteness, or late referral. The survival benefit beyond twelve months was also evident in Kaplan–Meier style survival curves (Supporting Information, figure 2).

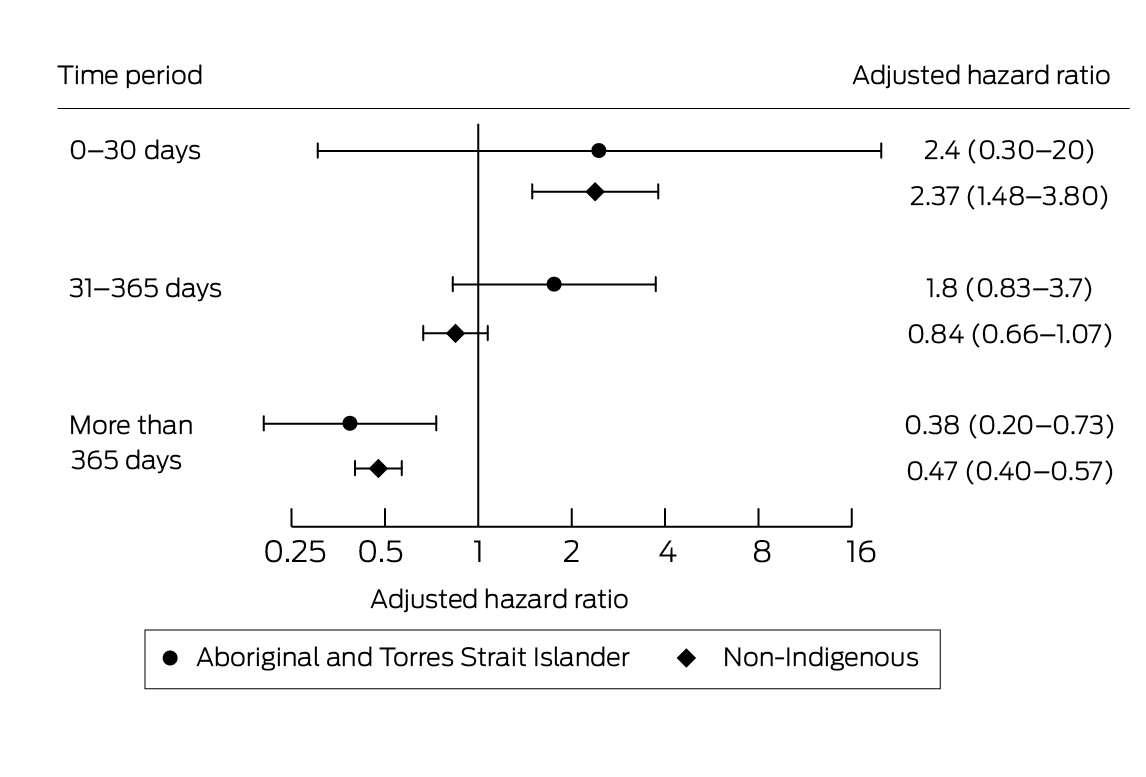

Of the 32 689 non‐Indigenous Australians who commenced dialysis during 1 July 2006 – 31 December 2020, 7984 were waitlisted for deceased donor kidney transplants (24%) (Supporting Information, figure 1, table 3); 6242 waitlisted people received deceased donor transplants (78%) (Supporting Information, table 4). The survival benefit for non‐Indigenous Australians — thirty days after transplantation: mortality aHR, 2.37 (95% CI, 1.48–3.80); thirty‐one days to twelve months: aHR, 0.84 (95% CI, 0.66–1.07); after twelve months: aHR, 0.47 (95% CI, 0.40–0.57) — was similar to that for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who received kidney transplants (Box 5). There was no difference in survival benefit between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and non‐Indigenous people (interaction: P = 0.16).

Discussion

We identified a significant survival benefit, after the first year, of kidney transplantation compared with remaining on dialysis for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who have at any time been on the deceased donor organ waiting list. This benefit, evident in both unadjusted analyses and after adjusting for a variety of selected demographic and clinical factors, was similar in timing and magnitude to that associated with kidney transplantation in non‐Indigenous Australians. Taken in conjunction with the strong and consistent message from the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community that transplantation is the treatment most likely to improve quality of life and connection to culture and Country,11 our findings should allay concerns about the benefit of kidney transplantation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and support initiatives across Australia to increase rates of transplantation.

During the first twelve months after transplantation, there was a statistically non‐significant greater risk of death, associated with major surgery and high‐dose induction immunosuppression. This finding is consistent with other reports.3 Deceased donor transplantation is offered only to people whose baseline life expectancy is reasonable and who are expected to tolerate the initial risks and derive a long term benefit.

The waitlisting rate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is alarmingly low. Despite being well enough to benefit from dialysis, only 11% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people commencing dialysis were waitlisted for transplants during 2006–2020, compared with 24% of non‐Indigenous patients commencing dialysis during the same period (Supporting Information, table 3). Determining who may benefit is complex. Waitlisting is the endpoint of an intensive process of referral, assessment, patient education, counselling, health optimisation and maintenance, and consent. Systemic biases at each level of this process are barriers for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.6,15 We reduced selection bias in our study by including only people waitlisted for transplants,3 but many people who may have benefited from transplantation were not waitlisted, for reasons including racism.16 It is likely that a substantial group of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with risk profiles similar to those of the waitlisted people included in our analysis would also benefit from transplantation, but were never waitlisted.

In our study, the survival benefit associated with transplantation was independent of geographic remoteness. However, this finding is limited by the lower numbers of people from rural and remote locations who were waitlisted. Geographic remoteness influences waitlisting and transplantation rates,5 as well as transplant outcomes,8 for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to a greater degree than for non‐Indigenous Australians. The assessment for transplantation relies on multiple interactions with mainstream health services in tertiary hospitals in state and territory capital cities, where institutional racism is pervasive.17 In the Northern Territory, most of which is classified as remote or very remote, the transplant waitlisting rate is lower than the national level, despite the territory having the highest national incidence of kidney failure (more than four times the national rate.18 The assessment process in the NT takes three times as long for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as for non‐Indigenous Australians.19 Multiple health system barriers result in significant delays and prevent some people being waitlisted at all.20 Health service redesign that prioritises an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workforce and local, coordinated, and streamlined clinical care pathways have been proposed as conduits for change.20

The longer median time from dialysis commencement to waitlisting in the transplant group suggests that a subset of people for whom the work‐up process took a long time received a kidney transplant relatively rapidly after being waitlisted.5 The kidney organ matching algorithm is based largely on waiting time from the date of commencement of kidney replacement therapy. Conversely, people who were rapidly waitlisted will be on the waiting list for a longer period before receiving transplants.

The survival benefit of transplantation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people was similar to that for non‐Indigenous Australians, despite the comparatively longer time to waitlisting. Overcoming the additional barriers faced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is the next step in achieving equity in transplantation outcomes. The National Indigenous Kidney Transplantation Taskforce (NIKTT) was a federal government‐funded, time‐limited initiative (2020–2022), established in response to community advocacy for health equity, strongly supported by clinicians and the Transplantation Society of Australia and New Zealand. The taskforce endorsed established community priorities, including enhanced data collection and sovereignty, evaluating cultural bias initiatives in health care systems, establishing reference groups of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with lived experience of kidney disease, and piloting alternative models of care that improve access to transplantation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.21 Taskforce activities culminated in a national gathering and the endorsement of a position statement that called for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander‐governed and community‐led changes22 to improve health system responsiveness.23

Low kidney transplantation rates have been reported for First Nations communities in other colonised lands, such as Canada, New Zealand, and the United States.24 The survival benefit of transplantation in these communities has not, however, been established. Our analysis should encourage work to improve equity in transplantation rates for First Nations people around the world.

Limitations

While ANZDATA case ascertainment and follow‐up is near complete,25 its dataset does not cover all variables relevant to our analysis, and the influence of unmeasured factors is possible. By restricting the analysis to people waitlisted for kidney transplantation, we reduced the selection bias associated with being deemed eligible for transplantation. People who had not received transplants by the end of the follow‐up period included some who would subsequently receive transplants, and others who would not because they died while waiting or were removed from the waitlist. As people can move onto and off the waitlist (because of an acute illness, for example), data regarding time on the waitlist is not reliable. As people who became unwell and were removed from the waiting list remained in the non‐transplantation group, selection bias in favour of the transplantation group is possible. Conversely, people who became unwell after transplantation also remained in the study.

We could not consider many factors that affect post‐transplantation survival, such as HLA matching and donor age, as they apply only to people who received transplants. The influence of HLA matching on survival after kidney transplantation is generally small,26 and the low number of transplants for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people would make a statistically powerful study difficult.

We could not assess systemic racism in health care systems or regional differences in practice and policy that influence transplant suitability assessment. Reasons for not waitlisting people were unavailable at the time of analysis, but were collected as part of the NIKTT project.

Our study was not sufficiently powered to detect differences in causes of death after transplantation or while on dialysis. We could not assess the personal burden of either treatment, including time spent away from community and Country, two major contributors to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander holistic views of health and wellbeing.27 Finally, we could not assess the benefit of living donor transplantation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, the rates of which have been consistently very low.2

Conclusion

From twelve months after transplantation, there is a substantial survival benefit for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who received deceased donor kidney transplants compared with those who remained on dialysis. Health professionals and the community should be better informed about this benefit. Supporting the access of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to kidney transplantation with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander‐governed programs is essential to achieving transplantation equity for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.

Box 1 – Community perspective of the work

To be able to stay on Country for treatment allows our people to continue ongoing connections to mother earth. She gives us strength to continue our ways and builds on our mindset to stay strong without added stressors. We are extremely disconnected when we must leave to access lifesaving treatment.

When you’re connected to Country, your family and cultural responsibilities the completeness is felt throughout our body, mind and spirit. We can continue our hunting for the nutrition value our bodies crave for our bush foods, keep caring for Country and be surrounded by family that know us and love us. Without transplantation for our people there is a breakdown in sharing knowledge, and practices stop. We need transplantation to allow our cultural ways to continue to thrive, not just survive.

The current system subjects our people to institutionalised racism over and over again. These traumatic encounters happen year after year (3 times a week, 150+ times a year, not including appointments). Long term benefits of transplantation for our people and communities can dramatically reduce this exposure, there should be no difference in the results, the access to transplant and equity in treatment and outcomes, however there is.

Kelli Owen, on behalf of the AKction reference group.

Box 2 – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who commenced dialysis during 1 July 2006 – 31 December 2020

Box 3 – Baseline characteristics of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people waitlisted for deceased donor kidney transplantation, Australia, 1 July 2006 – 31 December 2020

|

Characteristic |

Did not receive transplants |

Received transplants |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Number of people |

127 |

323 |

|||||||||||||

|

Age at commencement of dialysis (years), median (IQR) |

47 (35–54) |

43 (33–52) |

|||||||||||||

|

Age at waitlisting (years), median (IQR) |

49 (39–56) |

46 (36–55) |

|||||||||||||

|

Time from commencement of dialysis to waitlisting (days), median (IQR) |

618 (350–985) |

733 (350–1431) |

|||||||||||||

|

Time to from commencement of dialysis to transplantation (days), median (IQR) |

— |

1083 (659–1902) |

|||||||||||||

|

Sex (women) |

59 (46%) |

139 (43.0%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Body mass index (kg/m2), mean (SD) |

28.8 (6.6) |

28.7 (6.3) |

|||||||||||||

|

Haemodialysis (ie, not peritoneal dialysis) |

100 (79%) |

238 (73.7%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Late referral to nephrology care |

24 (19%) |

54 (17%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Other medical conditions |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Previously/currently smoked |

68 (54%) |

171 (53.4%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Diabetes |

69 (54%) |

171 (52.9%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Coronary artery disease |

29 (23%) |

44 (14%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Peripheral vascular disease |

15 (12%) |

21 (6.5%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Cerebrovascular disease |

5 (3.9%) |

9 (3%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Chronic lung disease |

11 (8.7%) |

15 (4.6%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Dialysis start date |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

2006–2010 |

29 (23%) |

101 (31.3%) |

|||||||||||||

|

2011–2015 |

31 (24%) |

148 (45.8%) |

|||||||||||||

|

2016–2020 |

67 (53%) |

74 (23%) |

|||||||||||||

|

State/territory at commencement of dialysis |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Northern Territory |

38 (30%) |

75 (23%) |

|||||||||||||

|

New South Wales |

30 (24%) |

55 (17%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Victoria |

9 (7.1%) |

27 (8.4%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Queensland |

28 (22%) |

75 (23%) |

|||||||||||||

|

South Australia |

4 (3.1%) |

26 (8.0%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Western Australia |

14 (11%) |

60 (19%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Tasmania |

2 (2%) |

1 (0.3%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Australian Capital Territory |

2 (2%) |

4 (1%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Remoteness14 |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Major cities of Australia |

25 (20%) |

69 (21%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Inner regional Australia |

22 (17%) |

53 (16%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Outer regional Australia |

25 (20%) |

77 (24%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Remote Australia |

24 (19%) |

49 (15%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Very remote Australia |

29 (23%) |

71 (22%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Missing data |

2 (2%) |

4 (1%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Cause of kidney failure |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Diabetic nephropathy |

69 (54%) |

153 (47.4%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Glomerulonephritis |

23 (18%) |

85 (26%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Hypertension |

10 (7.9%) |

35 (11%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Polycystic disease |

1 (1%) |

2 (1%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Reflux nephropathy |

5 (4%) |

16 (5.0%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Other |

9 (7%) |

20 (6.2%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Uncertain |

7 (6%) |

11 (3.4%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Not reported |

3 (2%) |

1 (0.3%) |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

IQR = interquartile range; SD = standard deviation. |

|||||||||||||||