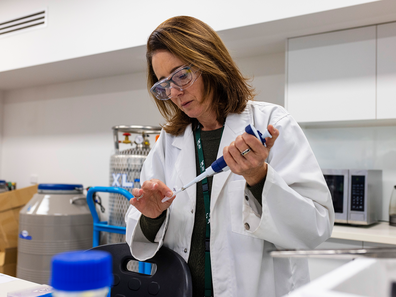

Dr Justine O’Brien’s job doesn’t sound real.

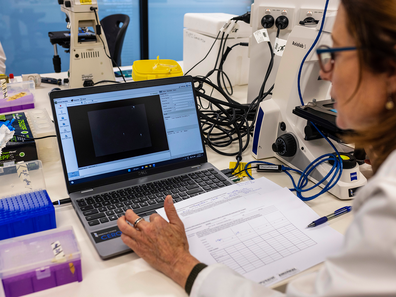

She explains it as she leads 9honey through Taronga’s Institute of Science and Learning and into a high-tech lab, where a little white dot wriggles on her laptop screen.

“That’s a frog sperm,” she says, pointing to the cluster of pixels.

READ MORE: No one knew what Sarah had stashed in her backseat driving through Sydney

Dr O’Brien does frog IVF. That’s the simplest way to explain her work on the zoo’s Frog Conservation Biobanking project.

As Manager of Conservation Science at Taronga, Dr O’Brien collects and cryopreserves the sperm of endangered native frogs to support conservation and breeding programs.

The goal is to maintain genetic diversity in wild and zoo populations so these little critters don’t go extinct due to habitat loss, climate change and disease.

It’s important work, but Dr O’Brien understands the funny looks when she tells people she artificially inseminates frogs for a living.

“I’ve had a lot of close friends call me certain names I can’t repeat,” she laughs. “You are a bit of a novelty piece.”

Like most Australian kids, Dr O’Brien grew up loving animals and dreamed of working with them – though she didn’t envisage working with frog eggs and sperm.

It started when she took a special interest in animal reproduction while studying science at the University of Sydney in the early 1990s, then undertook a PhD in veterinary science.

As any uni student would, she took up odd jobs and even worked at a human IVF clinic before graduating.

But once she’d finished her studies, she headed straight to the US to work in wildlife reproductive research.

Did she have trouble finding local work as a woman in STEM?

“No,” she says, “there weren’t any gender related barriers, but there were funding barriers in Australia at that time.”

With limited wildlife research opportunities Down Under, she spent 20 years in the US before Australia called her home in the mid-2010s.

That’s how she found herself wrangling native frogs in Taronga’s labs. And yes, ‘wrangling’ is often the appropriate word.

READ MORE: Catherine was working when a 200kg animal suddenly appeared above her

Quick, jumpy Booroolong Frogs often try to hop free while Dr O’Brien is collecting samples, so she and the other researchers, like University of Wollongong partners, need to have their wits about them.

Slow-moving Northern and Southern Corroboree frogs, on the other hand, make ideal patients.

“They’re more like walking frogs, I like collecting samples from them,” Dr O’Brien chuckles.

Aside from wriggly frogs, collecting samples is relatively easy because frogs reproduce outside the body.

A female releases eggs, which are fertilised by the male’s sperm-infused urine; that’s the stuff Dr O’Brien has to collect.

It starts with a little injection for the male frog, which releases a hormone usually produced during breeding.

“Then we essentially go in with a very fine pipette, we pick up the frog after they’ve had their hormone injection, and we just collect the urine,” O’Brien explains.

“Then we isolate that sample and put it through the freezing process […] it’s the same process that would be used for human IVF.”

Then when there’s a female frog ready to lay eggs, the appropriate sperm is thawed and carefully added to the eggs in a dish.

A few days or weeks later, the baby frogs emerge.

For a daily dose of 9honey, subscribe to our newsletter here.

So much time and science goes into hatching that handful of tiny animals that most Aussies barely notice at the zoo or in their own backyards, but that lack of awareness is why it’s so important.

Many native Australian frog species are facing declining population trajectories that have only been exacerbated by recent droughts and bushfires.

Corroboree frogs, Australia’s most critically endangered species, have been decimated by chytrid fungus, which is the primary cause of decline in frogs worldwide.

Without conservation efforts like amphibian IVF and biobanking at Taronga, these native critters could go extinct.

People like Dr O’Brien work day and night to make sure that doesn’t happen – and the work is paying off.

“A good case study is the Northern Booroolong frog. That population in the wild was in an extremely poor state after the extended drought and then the mega fires,” she says.

“An emergency intervention took place […] and that population was extracted and brought to Taronga. There were 58 animals that came here, and we knew that we had to get them breeding.”

Over the next three years, they worked tirelessly to collect and biobank samples and encourage natural reproduction. IVF trials, in conjunction with natural reproduction are planned for the next season.

The result of all that work was over 1200 frogs being released back into the wild across 2023 and 2024. That’s more than 20 times the original number Taronga took in.

There’s also hundreds of genetically diverse samples frozen safely in the zoo’s biobanks to ensure the species’ future, and that’s just the work they’ve done with Northern Booroolong frogs.

“Cryobanking and IVF and artificial insemination are important conservation tools, but they’re useless without healthy populations and habitats to work alongside them,” Dr O’Brien adds.

There’s so much research and conservation still ongoing at the zoo and she’s proud to be a part of that, even if the job earns her a few odd looks.

After all, there’s nothing more satisfying than seeing hundreds of juvenile frogs you helped make get released back into the wild.

“We’re having our findings come out of the lab [and] directly into conservation, and that’s really satisfying.”

FOLLOW US ON WHATSAPP HERE: Stay across all the latest in celebrity, lifestyle and opinion via our WhatsApp channel. No comments, no algorithm and nobody can see your private details.